Diagnosing gluteal tendinopathy in clinical practice

Gluteal tendinopathy is the most common local condition associated with lateral hip pain presentations. While previously misunderstood as an isolated condition of the trochanteric bursa (trochanteric bursitis), there is now a substantial and growing body of scientific literature outlining processes for diagnosing gluteal tendinopathy, diagnostic definitions, and treatment of gluteal tendinopathy and Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS).

Despite the availability of such evidence, recent survey studies of physiotherapists have highlighted that while there is widespread awareness of general principles, there is a considerable lack of fidelity in the translation of the evidence to clinical practice1,2.

Does it really matter? As long as clinicians have the general gist, will that be enough to provide optimal outcomes for those with lateral hip pain? In some cases, sure. If appropriately diagnosed, basic education and load management advice may suffice for some. However, if the diagnosis is incorrect or the exercises that are supplied do not consider the nature of the condition, the intervention may delay or confound rather than facilitate an optimal outcome.

The LEAP randomised clinical trial3 demonstrated that high success rates are possible when:

- the condition is well understood,

- patients are carefully screened with a battery of tests with established diagnostic utility and

- the intervention is well informed by evidence regarding pathoaetiological mechanisms and impairments.

Let’s take a look at what the survey studies reveal in terms of the current status of clinical translation of the evidence base for gluteal tendinopathy and greater trochanteric pain syndrome. One study surveyed physiotherapists in Australia, New Zealand and Ireland1, and another surveyed physiotherapists in the United Kingdom (UK)2.

What do physiotherapists understand Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome to be?

French and colleagues1 provided a definition of GTPS for survey participants: Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS) is an overarching term used to describe lateral hip pain, a painful condition of the gluteus medius and/or gluteus minimus tendons (gluteal tendinopathy), which may be associated with pathology of the trochanteric bursa (trochanteric bursitis).

The Stephens and colleagues survey2 of UK physiotherapists first explored their participants understanding of GTPS. They asked participants to select one of a number of statements that best reflected their understanding of the condition:

Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome is a term used to describe lateral hip pain in relation to

- A painful condition of the trochanteric bursa

- A painful condition of the gluteus medius and / or gluteus minimus tendon(s)

- A painful condition, primarily of the trochanteric bursa, with symptoms also potentially arising from the gluteus medius and minimus tendons

- A painful condition, primarily of the gluteus medius and / or minimus tendons, with symptoms also potentially arising from the trochanteric bursa

- An over-arching term used to describe lateral hip pain of unknown origin.

…more than one in three physiotherapists (36%) understood GTPS to be an ‘overarching term used to describe lateral hip pain of unknown origin’

Fifty-eight percent of physiotherapists surveyed in the UK indicated that GTPS was a condition primarily of the gluteal tendons, a view supported by the literature. However, more than one in three physiotherapists (36%) understood GTPS to be an ‘overarching term used to describe lateral hip pain of unknown origin’2.

This lack of specificity in ‘syndrome’ diagnoses may give rise to a lack of clarity in selection of diagnostic and management techniques, as I have discussed in a previous blog. This is consistent with Stephens et al’s finding that physiotherapists who understand GTPS as a condition primarily of tendinopathy were more confident in their diagnosis and treatment of the condition2. Of course, confidence does not necessarily correlate with evidence-based practice or success.

How confident are physiotherapists in diagnosing gluteal tendinopathy or greater trochanteric pain syndrome?

Two-thirds of surveyed physiotherapists in Australia, New Zealand and Ireland are very confident in their diagnosis of GTPS (245/361, 67.9%), with the highest proportion of very confident physiotherapists in Australia (75.8%)1. In the UK survey, surveyed physiotherapists were divided into those with a special interest and those without a special interest in GTPS. Not surprisingly, a significantly lower proportion (30.3% vs 64.8%) of those without a special interest were very confident in diagnosing GTPS2.

Confidence in the diagnosis of GTPS is generally high in physiotherapists, although those without any special interest in the condition are generally less confident.

Which diagnostic criteria do physiotherapists use to confirm a diagnosis of Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome in clinical practice?

From the patient interview, most surveyed physiotherapists identify gluteal tendinopathy/GTPS as a condition associated with lateral hip pain experienced in sidelying and/or on loading (e.g. walking)1,2. However, physical testing procedures are less consistent between physiotherapists and with recommendations from the literature.

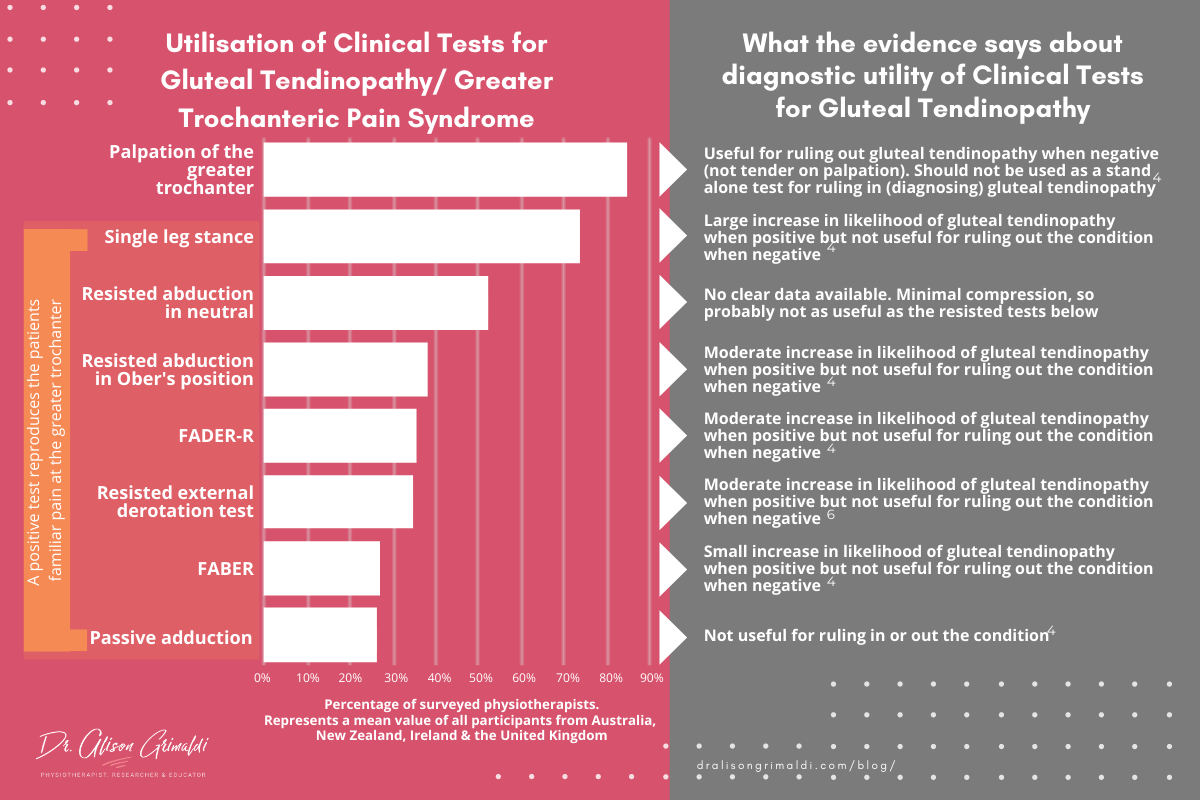

Direct compression (palpation) and combinations of compressive and tensile loads appear to be most useful for eliciting familiar pain in those with gluteal tendinopathy4. If we combine results for all countries, 84% of surveyed physiotherapists palpate the greater trochanter, two thirds consider pain on single leg stance (73%) and half (52%) perform resisted hip abduction in neutral.

Tenderness on palpation is considered a cardinal sign of gluteal tendinopathy and GTPS and yet around 1 in 10 physiotherapists do not use palpation of the greater trochanter in the diagnosis of the condition in clinical practice.

The single leg stand test (reproduction of lateral hip pain within 30 seconds of standing on one leg)5 has been shown to have high specificity, useful for increasing the likelihood of gluteal tendinopathy when positive, although not helpful for ruling out the condition when negative4.

No clear information exists to support resisted abduction in neutral in the diagnosis of this condition, the third most commonly used test by clinicians. Ganderton and colleagues did test resisted abduction in inner range (45degrees of abduction) and found it highly specific6, however specificity is determined by measuring effects in the control group.

When the control group is asymptomatic, as in this study, high values for true negatives and low values for false positives are usually easily achieved, resulting in a high specificity value. This can overinflate the potential value of a test in clinical practice, where you are not assessing painfree individuals but those with lateral hip pain associated with an unknown source prior to testing.

This is the primary reason that the study we conducted at the University of Queensland4 only included symptomatic participants reporting pain at the lateral aspect of the hip. This is much more consistent with the differential diagnosis process that clinicians need to perform, making specificity and positive likelihood ratio results more robust and clinically meaningful.

Despite high levels of confidence in the diagnosis of GTPS, there appears to be overreliance on 2-3 physical tests and underutilisation of a number of tests with good diagnostic utility.

From the remaining results, it appears that physiotherapists are underutilising a number of useful tests. Only around one third of surveyed physiotherapists are applying specific tests that have been developed to combine compressive and tensile loads on the gluteal tendons, such as the FADER-R test (Hip flexion/Adduction/External Rotation + isometric internal rotation) (35%), the ADD-R test (Hip adduction in modified Ober’s position + isometric abduction) (38%), or the resisted external derotation test (resisted internal rotation from a position of hip flexion and external rotation) (35%). These tests have all been shown to be useful in the diagnosis of gluteal tendinopathy, producing a moderate increase in likelihood of gluteal tendinopathy on imaging4,6.

The value of a comprehensive test battery for diagnosing gluteal tendinopathy in clinical practice

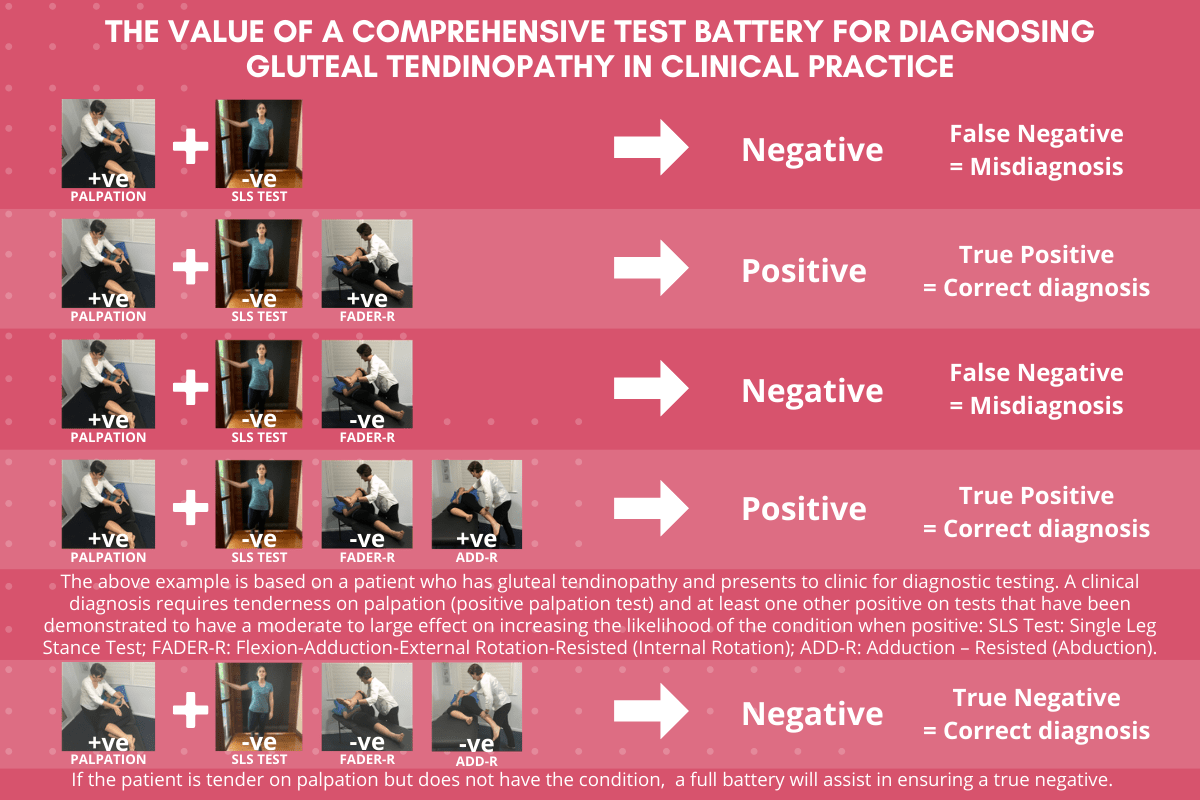

In many cases, selecting only 2-3 tests for gluteal tendinopathy/greater trochanteric pain syndrome may not be adequate for achieving a correct diagnosis.

Outlined in the graphic below is an example based on a patient who has gluteal tendinopathy and presents to clinic for diagnostic testing. A clinical diagnosis requires tenderness on palpation (positive palpation test) and at least one other positive on tests that have been demonstrated to have a moderate to large effect on increasing the likelihood of the condition when positive.

If the patient is tender on palpation but not painful on the single leg stance test and your assessment ends there, your conclusion would be that the patient does not have gluteal tendinopathy (false negative). Tenderness on palpation alone is not adequate for a diagnosis of gluteal tendinopathy/GTPS as many people are tender over the greater trochanter without necessarily having gluteal tendinopathy/GTPS (low specificity)4,6.

If you then perform another specific test such as the FADER-R test, if the test is positive you would then arrive at a correct positive diagnosis. However, some patients with gluteal tendinopathy may test negative on both the single leg stance and FADER-R test and yet will test positive on the ADD-R test (resisted abduction in modified Ober’s test position). Or sometimes test results may be equivocal – the patient is not quite sure whether the response they feel is pain or stretch on the FADER-R test, or ‘their pain’. Performing a further test from the battery, like the ADD-R test will then assist with achieving a true positive test. Alternatively, a patient who is tender on palpation and yet negative on all three of these tests is unlikely to have the condition.

Performing a battery of tests that includes both sensitive (palpation) and specific tests (SLS Test, FADER-R/External derotation test, ADD-R), should reduce the risks of misdiagnosis in clinical practice.

The FABER (Flexion/Abduction/External Rotation) test has also been shown to be useful for differentiating GTPS from hip osteoarthritis (OA)7 (Fearon et al 2013-6), and yet is utilised by only about one quarter of physiotherapists surveyed in both these studies1,2. Those with reproduction of their lateral hip pain on FABER and tenderness on palpation of the greater trochanter without reported difficulty manipulating their shoes and socks, are more likely to have GTPS than hip OA. Be mindful of those who report difficulty with putting on their socks and have restriction in their FABER – further joint specific tests should be performed.

Including the FABER test can assist in differentiating gluteal tendinopathy/GTPS from osteoarthritis or joint-related pain. This test should be included in any assessment of patients presenting to clinic with lateral hip pain.

Why are two-thirds of physiotherapists not performing a full test battery?

Application of a wider battery of tests may aide in ensuring a correct diagnosis, and yet two-thirds of physiotherapists are not utilising a number of valuable tests in their clinical practice.

Clinicians may be underutilising available tests due to:

-

Time pressures

-

Confidence in performance of most utilised tests - palpation, single leg stance test and resisted abduction

-

Lack of familiarity and confidence with more specialised tests.

In everyday practice, clinicians are often under time pressure to perform their physical assessment, reach a diagnosis and move on to treatment, which after all is why most patients attend – to be treated, right? However, short cuts in the assessment phase, both in the patient interview and physical assessment, may lead to misdiagnosis and therefore poor or delayed outcomes. With good education and discussion with the patient, most will see the value of the extra time spent in this initial phase and appreciate the time the clinician invests to try to get the diagnosis and therefore management plan correct from the start.

Familiarity and confidence in the application of physical tests is also likely to be a factor influencing which tests are most commonly applied by clinicians. Palpation and resisted abduction are learnt as basic skills in undergraduate training. Assessing single leg stance is also a basic physiotherapy skill, although the single leg stance test used for diagnosing gluteal tendinopathy or GTPS is not an assessment of pelvic control but a pain provocation test, so fidelity in the application of this test is important in the diagnostic process.

In the UK survey study, participants with a special interest in GTPS were more likely to use the single leg stance test, the FABER test and the resisted external derotation test, while those without a specialist interest where more likely to select resisted hip abduction in neutral2. This suggests that those who have a special interest in the condition may have spent time upskilling or familiarising themselves with the application procedure and interpretation of other tests.

The relationship between confidence and performance is complicated. Confidence may reduce knowledge seeking behaviour. If physiotherapists feel highly confident in diagnosing gluteal tendinopathy or GTPS on the basis of 2-3 tests, they may not feel the need to seek further information to improve their clinical practice. Or if clinicians are aware that other tests are available but are unsure of how to perform or interpret the tests, the lack of knowledge may reduce confidence and likelihood of applying these tests.

Healthcare is an ever-evolving science and practice. Researchers have a responsibility to improve awareness and translation of the evidence into clinical practice, and clinicians have a responsibility to ensure their practice is optimally informed by the evidence base available.

Sign up to our newsletter to receive updates on upcoming courses, news and special offers.

References

- French H, Grimaldi A, Woodley S, O'Connor L, Fearon A. An international survey of current physiotherapy practice in diagnosis and knowledge translation of greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS). Musculoskeletal Science & Practice 2019;43:122-126

- Stephens G, O'Neill S, French HP, Fearon A, Grimaldi A, O'Connor L, Woodley S, Littlewood C. A survey of physiotherapy practice (2018) in the United Kingdom for patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Musculoskeletal Science & Practice 2019;40:10-20

- Mellor R, Bennell K, Grimaldi A, Nicolson P, Kasza J, Hodges P, Wajswelner H, Vicenzino B. Education plus exercise versus corticosteroid injection use versus a wait and see approach on global outcome and pain from gluteal tendinopathy: prospective, single blinded, randomised clinical trial. British Medical Journal 2018;52(22):1464-1472.

- Grimaldi A, Mellor R, Nicolson P, Hodges P, Bennell K, Vicenzino B. Utility of clinical tests to diagnose MRI-confirmed gluteal tendinopathy in patients presenting with lateral hip pain. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017;51(6):519-524

- Lequesne M, Mathieu P, Vuillemin-Bodaghi V, et al. Gluteal tendinopathy in refractory greater trochanter pain syndrome: diagnostic value of two clinical tests. Arthritis & Rheumatology 2008;59:241-246

- Ganderton, C., Semciw, A., Cook, J. and Pizzari, T., 2017. Demystifying the Clinical Diagnosis of Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome in Women. Journal of Women's Health, 26(6), pp.633-643.

- Fearon AM, Scarvell JM, Neeman T, Cook JL, Cormick W, Smith PN. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: defining the clinical syndrome. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2013;47:649-653.