Acetabular Dysplasia – Are you seeing the whole picture?

June is Hip Dysplasia Awareness month. You may be aware of dysplasia, but are you seeing the whole picture? Acetabular dysplasia is one of the leading causes of hip instability and painful hip osteoarthritis and therefore awareness and early detection are of high importance. Dysplasia refers to abnormal growth, in this case of the bones of the hip. Variations in shape of the femoral head and neck may develop during childhood and adolescence, predisposing to Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome (FAIS). Most commonly though, dysplasia of the hip is used to denote under-development of the acetabulum during infancy and childhood. (Read more about Development and Prevention of Acetabular Dyplasia here) While cam morphology of the femur and associated FAI have been the subject of much attention in recent years, there remains inadequate recognition of acetabular dysplasia with diagnosis often delayed. In an infant, the condition is usually relatively easily addressed by avoiding swaddling of the legs and use of positioning to assist ideal formation of the acetabulum. If the diagnosis is missed until symptoms develop, often in the teens or early 20’s, medical intervention may require major bony reconstructive surgery with accompanying risks.

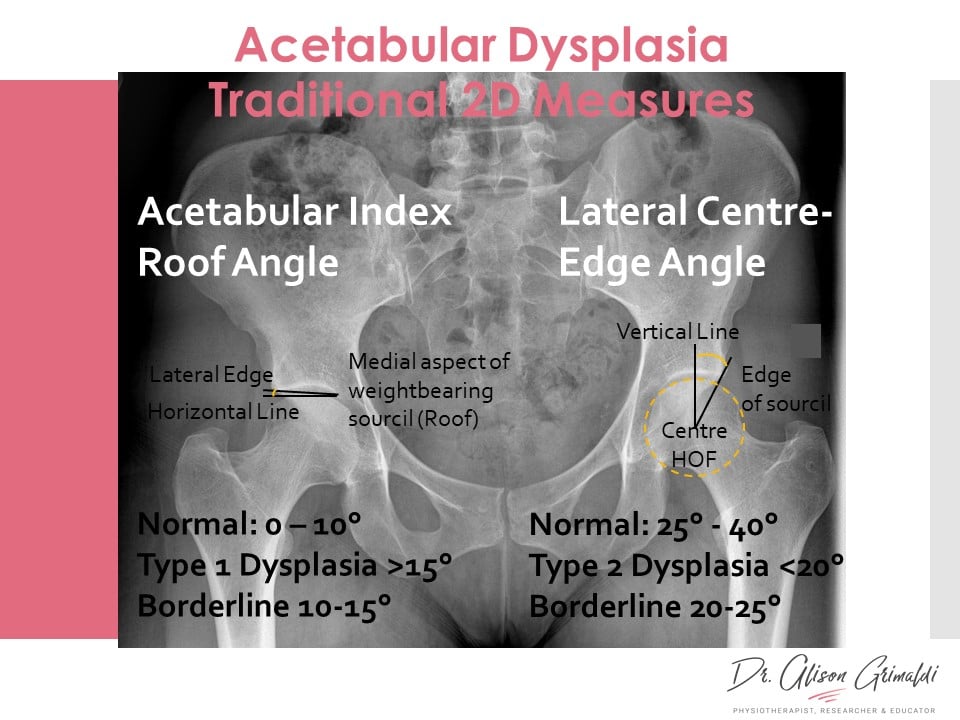

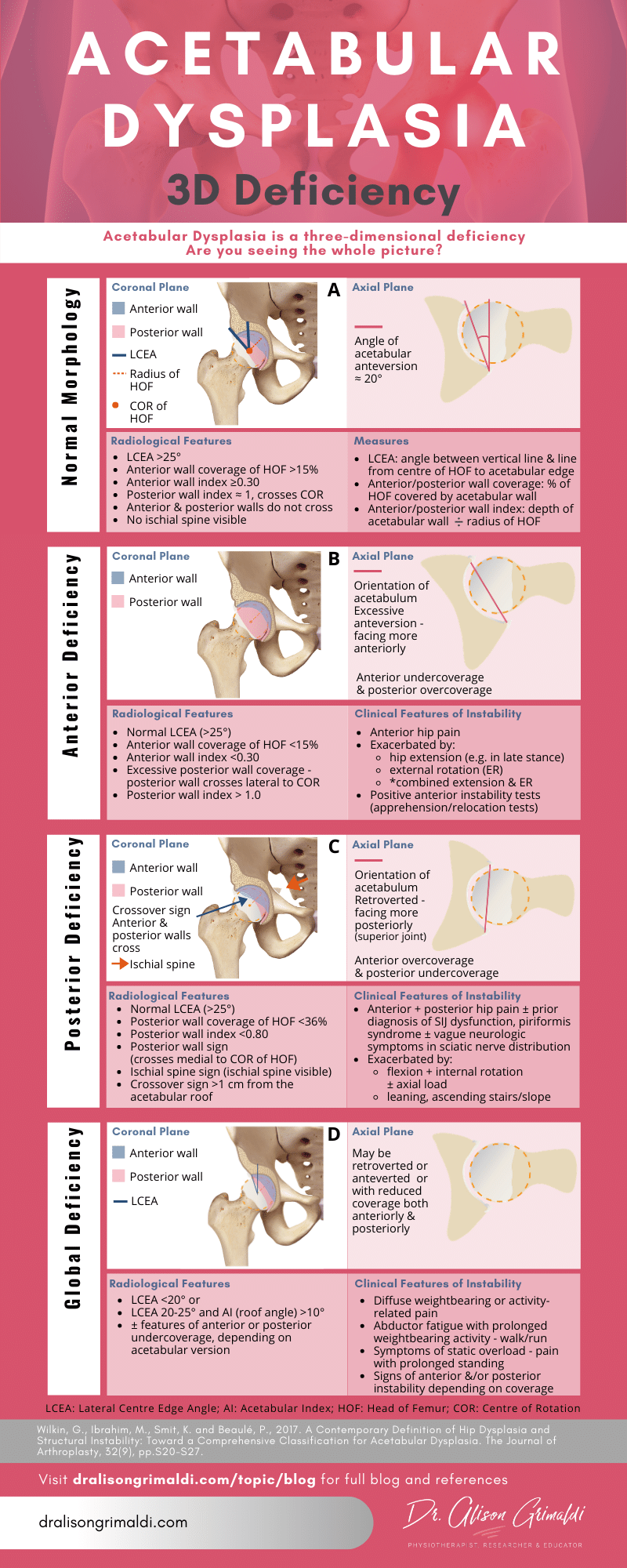

Even once symptoms present, there may be a delay in diagnosis if there is reliance on simple, traditional 2-dimensional assessments of the 3-dimensional acetabular shape. There are many different measures now available to describe the shape and orientation of the acetabulum, but the most commonly used techniques are still the traditional measurements of Acetabular Index or Roof Angle and the Lateral Centre Edge Angle (LCEA) on an AP X-Ray.

Traditional Measures and Definitions of Acetabular Dysplasia

Type 1 acetabular dysplasia – angled roof

The traditional model of acetabular dysplasia describes 2 types of Dysplasia. Type 1 is where the acetabulum is shallow and the roof of the acetabulum is more upwardly slanted, predisposing to superolateral subluxation of the head of the femur. An acetabular index or roof angle of less than 10° is normal but more than 10-15° is considered dysplastic with higher risks of instability (see graphic above).

Type 2 acetabular dysplasia – short roof

In Type 2 dysplasia, the angulation of the roof may be less than 10° but the roof is short, providing less coverage of the femoral head. The Lateral Centre Edge Angle (LCEA) is the angle between a line from the centre of the head of the femur to the lateral edge of the weightbearing surface of the acetabulum and a vertical line (see graphic above). An LCEA of less than 20° is usually considered dysplastic, but as with most definitions, no-one agrees on exactly what is normal and therefore we end up with grey zones usually referred to as borderline dysplasia (LCEA 20-25°). These are still useful quick initial screening measures but if that’s all you look at, then you might not be seeing the whole picture. Those with either anterior or posterior acetabular deficiency and associated instability may present with a normal LCEA and acetabular index.

Contemporary Measures and Definitions of Acetabular Dysplasia

Wilkin and colleagues (2017) proposed a contemporary model for defining acetabular dysplasia and structural instability, denoting 3 classifications – Anterior, Posterior and Lateral or Global Instability1. These definitions denote presentations of structural deficiency of the acetabulum, together with signs and symptoms of instability. In the graphic below, each of these classifications is outlined and graphically displayed to highlight the 3-dimensional nature of acetabular dysplasia.

There are 3 main patterns of acetabular insufficiency or undercoverage of the femoral head:

1. Anterior Instability associated with Anterior Acetabular Deficiency

Despite adequate lateral coverage of the femoral head, indicated by a normal LCEA (>25°), the anterior femoral head may be inadequately covered by the acetabulum. This may be due to excessive anteversion of the acetabulum i.e. the acetabular cup faces more anteriorly. A normal amount of acetabular anteversion is around 20°from the sagittal plane (Figure A). Excessive acetabular anteversion will result in reduced anterior coverage and increased posterior coverage of the femoral head (Figure B), predisposing to both anterior instability and posterior joint impingement with a close interplay between the two.

Acetabular wall indices can provide more clarity on orientation of the acetabulum on an AP radiograph. Siebenrock and colleagues (2012) devised a method of measuring the amount of anterior or posterior coverage of the femoral head by the acetabular wall2. This is achieved by measuring the length of the anterior or posterior wall that covers the femoral head by drawing a line along the head-neck axis from the circumference of the femoral head to the point at which the wall crosses the head, and dividing this measurement by the radius of the femoral head. A value of 1 means that the wall crosses the femoral head exactly at the centrepoint of the femoral head. Femoral head coverage can also be expressed by the percentage of the femoral head that is covered by the anterior wall on an AP radiograph3.

Wilkin et al1 suggest that someone with a normal LCEA (>25°) who has an anterior wall index of <0.3, with <15% anterior coverage and excessive posterior wall coverage (Figure B), has the radiological features of anterior deficiency. Concurrent clinical features including anterior hip pain on hip extension (such as end stance phase) and external rotation, and positive anterior instability tests (apprehension/relocation tests), together increase the likelihood of a diagnosis of anterior instability associated with acetabular dysplasia. While anterior instability may be associated with developmental shape of the acetabulum, excessive surgical acetabular rim trimming may result in iatrogenic anterior instability.

2. Posterior Instability associated with Posterior Acetabular Deficiency

Posterior instability of the hip joint is less well-recognised than anterior instability, outside the context of major trauma or post-arthroplasty. However, there is rising awareness of low-energy posterior dislocation and the role of bony shape. Posterior acetabular deficiency, despite a normal LCEA, has been reported in young patients investigated following low-energy posterior dislocation4. This bony presentation is usually associated with acetabular retroversion. Acetabular retroversion is recognised as a cause of pincer femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) with impingement anteriorly occurring earlier due to the relative overcoverage of the femoral head. What is not so well recognised is with the anterior overcoverage comes a posterior undercoverage of the femoral head and therefore an increased risk of posterior instability (Figure C). Furthermore, early anterior impingement during flexion or internal rotation associated with either pincer or cam FAI, results in a levering of the head of the femur posteriorly. So, it is important to always consider the possibility of posterior instability in those with pincer &/or cam FAI.

Radiographic signs of posterior wall deficiency include posterior coverage of the head of the femur of less than 36%, a posterior wall index of <0.80 and a posterior wall sign (posterior wall crosses medial to the centre of the femoral head)1. Other signs of retroversion also increase suspicion of posterior undercoverage, such as the cross-over sign - where the line of the anterior wall crosses the posterior wall - and the ischial spine sign5, where the ischial spine becomes visible on an AP X-Ray (Figure C).

Clinically, patients with posterior instability may present with anterior and/or posterior pain due to the associated anterior impingement. Posterior pain is usually associated with positions or activities that load the posterior joint and/or uncover the femoral head posteriorly – hip flexion, internal rotation, anterior pelvic tilt and forward lean in standing e.g. bending or walking uphill or upstairs. Posterior instability often gives rise to protective increases in posterior muscular co-contraction, which may then irritate adjacent or transiting nerves. Many of these patients go for years being diagnosed with piriformis syndrome, deep gluteal syndrome, SIJ dysfunction1 or lumbar radiculopathy, with elbows and needles in the buttock or persistent stretching only ever providing short term relief. Clinical tests for posterior instability should be performed for anyone presenting with such symptoms.

3. Global/Lateral Instability associated with Lateral or Global Deficiency

Lateral or global instability (Figure D) is usually associated with ‘classic’ acetabular dysplasia with a LCEA of less than 20° +/- subluxation of the femoral head, with those falling between 20 and 25° categorised as borderline dysplasia1. Wilkin et al suggest that additional anterior and or posterior wall deficiency, and symptoms of static overload (such as pain with prolonged standing) and/or abductor fatigue (such as pain with prolonged walking/jogging), increase suspicion of lateral or global instability1.

Keep in mind that while acetabular dysplasia is a key factor predisposing to instability of the hip joint, other factors also play a role, such as:

- femoral shape (head-neck morphology, neck-shaft morphology, femoral version)

- labral or capsular deficiency (natural morphology, injury/overload, iatrogenic - post arthroscopic surgery)

- spinopelvic function (excessive anterior, posterior or lateral pelvic tilt)

- adequacy of dynamic muscular support systems

I hope this blog helps increase awareness, not just of the presence of acetabular dysplasia but of the three-dimensional nature of acetabular dysplasia. The radiographic features discussed are useful for extracting valuable additional information from a standard AP X-Ray but the image is still only 2 dimensional and for valid interpretation, patient positioning and image quality needs to be ideal. Where warranted, a CT scan will provide a true 3-dimensional representation of acetabular shape and coverage of the femoral head.

To identify cases of hip instability in clinical practice:

- Listen to the symptoms

- Perform physical tests for instability and

- Don’t rely on Lateral Centre Edge Angle for a diagnosis of acetabular dysplasia.

Make sure you're seeing the whole picture!

References

- Wilkin G, Ibrahim M, Smit K and Beaulé P. A Contemporary definition of hip dysplasia and structural instability: Toward a comprehensive classification for acetabular dysplasia. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9):S20-S27.

- Siebenrock KA, Kistler L, Schwab JM, Buchler L, Tannast M. The acetabular wall index for assessing anteroposterior femoral head coverage in symptomatic patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:3355–3360.

- Tannast M, Hanke M, Zheng G, Steppacher S and Siebenrock K. What are the radiographic reference values for acetabular under- and overcoverage? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2014;473(4):1234-1246.

- Mayer SW, Abdo JC, Hill MK, Kestel LA, Pan Z, Novais EN. Femoroacetabular impingement is associated with sports-related posterior hip instability in adolescents: a matched-cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:2299e303.

- Kalberer, F., Sierra, R., Madan, S., Ganz, R. and Leunig, M., 2008. Ischial Spine Projection into the Pelvis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 466(3), pp.677-683.

Want to learn more? Extend your knowledge here:

Another great Anterior Hip Pain blog

Anterior Hip Pain: Causes & Contributing Factors

Adequate consideration of individual causes and contributing factors is important for best outcomes.