Gluteal Underactivity – the quest for Goldilocks Glutes – Part 1

As health and exercise professionals, we are becoming ever more mindful about our language and how patients interpret what we say. Patients frequently report that they’ve been told their glutes don’t work, which can be understandably concerning, and in some cases becomes a single-minded focus for the patient - reactivating their ‘paralysed’ musculature. Others become equally evangelical about making sure they do not turn on their glutes, due to the interpretation of education about harmful ‘butt gripping.’ So, what is the truth of the matter? Does motor drive within the gluteals change or is it simply about size and strength? If it does change, what factors may alter this drive and what is the secret to achieving those Goldilocks Glutes! (The 'just right' factor - for those who aren't familiar with Goldilocks and the Three Bears 🙂 )

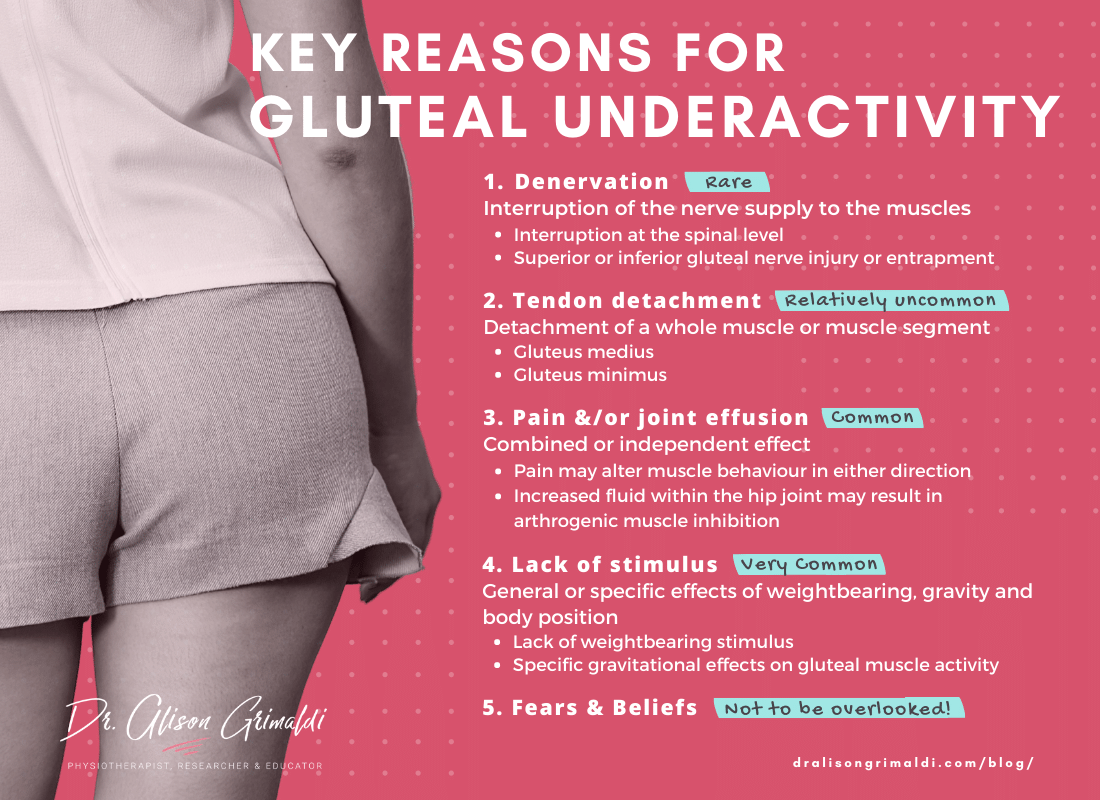

Key reasons for gluteal underactivity

Gluteal underactivity associated with denervation

Denervation is perhaps the least common reason for altered gluteal muscle activation, so in most circumstances, fears about paralysed muscles can be alleviated. However, interrupted nerve supply may occur at a spinal level or more locally in the buttock associated with peripheral entrapment or iatrogenic injury to the gluteal nerves. Injury to the inferior gluteal nerve will result in altered supply to the gluteus maximus, and subsequent atrophy and extension weakness. Superior gluteal nerve injury affects the hip abductor synergists, resulting in abductor weakness and atrophy, usually with an obvious pelvic drop in gait or single leg stance.

Gluteal underactivity associated with tendon detachment

Tendon tears are reasonably common in those with gluteal medius and minimus tendinopathy. Most of these are partial thickness or full thickness tears in a small area of the tendon, and in themselves do not prevent activation of a muscle segment. However, in more severe conditions a whole muscle segment or the whole muscle may become detached from its bony insertion. The muscle fibres may still be able to exert a little force via capsular or fascial attachments but the understimulated muscle invariably atrophies.

Gluteal underactivity associated with pain and/or joint effusion

Pain and joint effusion have both been shown to induce significant change in motor behaviour. Their effects may be additive or competitive. Experimental increase in hip joint fluid has been shown to reduce activity in gluteus maximus, in the absence of pain.1 The response to painful joint effusion however, is likely to be more variable due to inconsistent (flexible) changes in multiple levels of the motor system in response to pain. The traditional pain adaptation theory assumed a uniform inhibition of motor drive to muscles that are painful or create pain through their action. There is ample evidence now to show that there is no single motor response to pain. A newer theory agrees that pain adaptation has a primary purpose to reduce pain and protect the painful region, but the solutions are more flexible than once understood.2

Hodges & Tucker2 theorised that the adaptation to pain:

i) involves redistribution of activity within and between muscles;

ii) includes changes in mechanical behaviour evident in alterations of movement and muscle stiffness;

iii) aims to protect from pain or threatened pain or injury;

iv) involves changes at different levels throughout the motor system which may facilitate similar or opposite motor responses;

v) provides short term benefit but with potential long term adverse consequences as the adaptive motor changes often persist after pain has eased.

What this means is that the motor system will not always behave in a predictable manner in response to pain or injury and that the spinal cord (reflex response) and the brain may have different ideas about how the muscles should best protect the area. Health professionals will need to evaluate the cumulative response of each individual's motor system, to determine the best course of action for achieving rehabilitative goals.

The response of the motor system is rarely to inhibit a whole muscle group or even the whole muscle but redistribute muscle recruitment in a way in which the nervous systems 'thinks' should reduce pain and maintain function. This is why EMG studies might show reduced or delayed activation in some muscles within a synergy or segments within a muscle, and yet higher, earlier or sustained activation in others, in the presence of painful hip pathologies such as hip osteoarthritis3 or gluteal tendinopathy.4

Perhaps there is a little naivety in expecting a simple cue such as 'squeeze the buttock' to address this complex and variable response of the motor system. Might we do more harm than good applying such gross strategies? Maybe (read more in next month's blog about overactivation). Should we just ignore these alterations and hope they sort themselves out, or accept that the motor system has induced these changes because it really does know best? While pain is a potent stimulus for often useful self-protection in the short term, once pain has eased, the stimulus to revert to pre-existing strategies is not so great.2 The pain has settled, no danger here, why change?? As most of you will have experienced, a patient may present months or years after an injury or pain episode, with a new site of pain related to the load redistribution put in place and left in place by the motor system.

Motor adaptations that result in significant, inefficient and potentially harmful shifts in load sharing, should be addressed, but we may need to have some other tools in our rehab tool-bag, apart from that big hammer - 'squeeze your glutes.' I'm not saying we should never use this cue, but we need to be mindful of its limitations, ensure it is appropriate for the individual, tailor its application, monitor the effects of that cue and ensure we are not just replacing one inefficient strategy with another.

Gluteal underactivity related to lack of stimulus

There are many reasons for gluteal underactivity that are not related to pain but simply to a lack of stimulus. This might be a general lack of stimulus or more specific effects of weightbearing, gravity and body position.

Lack of weightbearing stimulus

The gluteals serve their greatest purpose in weightbearing function. The old adage - 'use it or lose it' - does indeed express a general truth. Sit on your bottom all day and your glutes may shrink and potentially alter motor behaviour associated with the lack of stimulus.

A review of the wealth of research on the effects of unloading, reports:

- effects are predominantly on skeletal muscles responsible for maintenance of posture and ground support - slow-type muscles with high levels of slow-twitch fibers.

- there are shifts of muscle fiber phenotypes and contractile properties from slow-twitch to fast-twitch type

- that these shifts are influenced by neural (shift from tonic to phasic activity) and metabolic factors.5

In effect then, if the body is not used enough for weightbearing function, the muscles responsible for supporting the body against gravitational load, including the gluteals, atrophy and change their normal antigravity behaviour.

Specific gravitational effects on gluteal muscle activity

More specifically, how gravity interacts with body position will have a potent effect on external moments and muscle activation. It's just physics! Muscles need to react to produce corresponding internal moments to balance the external forces imposed on the body. If the body position is such that external moments are low, there will be reduced requirement for a balancing muscle force. Why use a muscle when you really don't need to?

For example, when standing upright with the centre of mass of the trunk fairly well centered over the hip joint and the knees straight, the requirement for gluteus maximus activity is very low. Lean forward and the hip extensors kick in, lean back and the hip flexors kick in and the gluteus maximus has a rest - simple physics! This applies similarly in dynamic function - put your hands on your lower gluteus maximus and do a mid range squat with your trunk upright; now repeat with your trunk inclining forward. In which version did you feel most gluteal activation? The version with the trunk forward, right?

By manipulating simple natural stimuli such as these, we can often address gluteal underactivity efficiently while avoiding the flipside of volitional overactivation or sometimes harmful beliefs. Let's use gravity to our advantage!

Fear & Beliefs

What a person fears or believes about gluteal activation, movement or injury can also contribute to gluteal underactivity. For example, someone who believes that bending forward will injure their back may be so fearful that they replace bending with squatting, and perform this task almost exclusively with knee flexion and ankle dorsiflexion, keeping their trunk upright. Such movement adaptations will redistribute loads to the knee and ankle and reduce the natural stimulus imparted to the gluteals in everyday forward leaning and bending tasks.

Unhelpful beliefs about gluteal activation may also be developed in response to a comment from a health or exercise professional. Take the patient who presented to our clinic last week who was totally focused on making sure her gluteals did not activate. She reported that she had been told she was a 'butt gripper' and that she needed to stop activating her gluteals. Her interpretation was that any activation of her gluteals could be very dangerous to her condition. The issue was more in the interpretation of what was said. I'm sure the health professional did not intend the patient to develop the belief that she should shelve her glutes for the long term. But once this idea is entrenched, it can be quite difficult and time consuming for another health professional to unravel. Sometimes it might seem easier to get a message across by talking in black and white terms - 'your glutes won't turn on' or 'don't turn your glutes on.' It can be difficult to know how someone will interpret your message, so here are a couple of easy tips:

a. be mindful of what you say and try to avoid using polarising statements that may be fear inducing,

b. take the time to ask the patient what they are taking away from what you've said, and if they have any questions or concerns. That little extra time in the early education phase can save much mental anguish suffered by the individuals we mean to help.

The quest for Goldilocks Glutes

Next time you evaluate someone's glutes and determine that they have gluteal underactivity, think about these key reasons - rule out the rarer but important causes - then see what can be done to address the more common causes.

- Pain management will be a central factor in rehabilitative environments.

- Control effusion through load management education, monitoring and addressing specific mechanisms of localised overload. In some circumstances, short-term pharmacological management of inflammatory effusion may be required.

- For some with significant arthrogenic inhibition, neuromuscular electrical stimulation could be considered6, but this is most helpful for the more superficial gluteus maximus muscle and/or those with lower BMI and higher pain tolerance. Deeper muscles can be activated but the deeper the muscle the higher the stimulus required, which can be intolerable particularly for those with high pain levels or sensitivity.

- Increase general gluteal stimulus by increasing time spent weightbearing, while monitoring any pain and effusion.

- Increase specific stimulus by using gravity, body and joint position to your advantage.

- Take care with how you engage the top level of the motor system (the brain).

- No one approach works for all, test an intervention and monitor the outcome.

In our quest for optimal gluteal bulk, strength and activation, 'Goldilocks Glutes,' let's just make sure we don't go too far and induce gluteal overactivity, inefficiency and overload. We'll discuss this further in the next blog.

Learn more about hip muscle function, musculoskeletal loads and how we can optimise these in the rehabilitation of hip, groin and buttock pain. Multiple sessions to suit a wide range of timezones.

Lateral Hip & Buttock Pain 24-25th June 2023 - Registrations close May 15th

Sign up to our newsletter to receive updates on upcoming courses, news and special offers.

References