Iliopsoas Release: Beliefs, Indications, Techniques

The iliopsoas, our primary hip flexor muscle, is commonly demonised in both clinical practice and online environments. Tightness of the psoas or iliopsoas musculotendinous complex is assumed to be the root cause not only of anterior hip pain, but various physical ailments well beyond the hip and lumbar spine. The iliopsoas and its unfortunate owner are often subjected to painful manual therapy techniques claiming to ‘release the iliopsoas’, or worse still, often unnecessary and potentially disabling surgical iliopsoas release. It really is time to rethink iliopsoas release in rehab and surgery. Across 2 blogs, I’ll be diving deep into iliopsoas release beliefs, indications and techniques (this blog), and then stay tuned for next month where I’ll be presenting the case against iliopsoas release.

Here are the primary topics we’ll be talking about in this month's blog:

Common beliefs about the iliopsoas, hip pain and tightness

Anatomy and function of the iliacus and psoas (iliopsoas) muscles

Reported indications for iliopsoas release or surgical iliopsoas tenotomy

Discover our Anterior Hip & Groin Pain Course

If you enjoyed this blog, you might like to take the online course on Anterior Hip & Groin Pain - 5 hours of guided online video content. Better your skills and understanding of the anterior hip and groin and become equipped with the knowledge to administer clinical diagnostic tests and management strategies.

Common beliefs about the iliopsoas, hip pain and tightness

When it comes to hip pain and injury, the most common beliefs about the iliopsoas are firstly related to its role as a source of anterior hip pain and secondly to the underlying reason for these suspected iliopsoas issues – tightness or overactivity. While the iliopsoas can of course be a source of hip pain and may become relatively shortened, these assumptions are so often false and made in the absence of careful assessment by an evidence-based health professional.

False assumptions may lead to poor outcomes, as well as time and financial losses and the psychological burden of such beliefs and failed recovery. Surgical interventions based on false assumptions may have even greater adverse impacts, leaving the patient with long term hip flexor deficiency and variable levels of pain and disability depending on the situation.

Anatomy and function of the iliacus and psoas (iliopsoas) muscles

Anatomy of the iliopsoas muscle

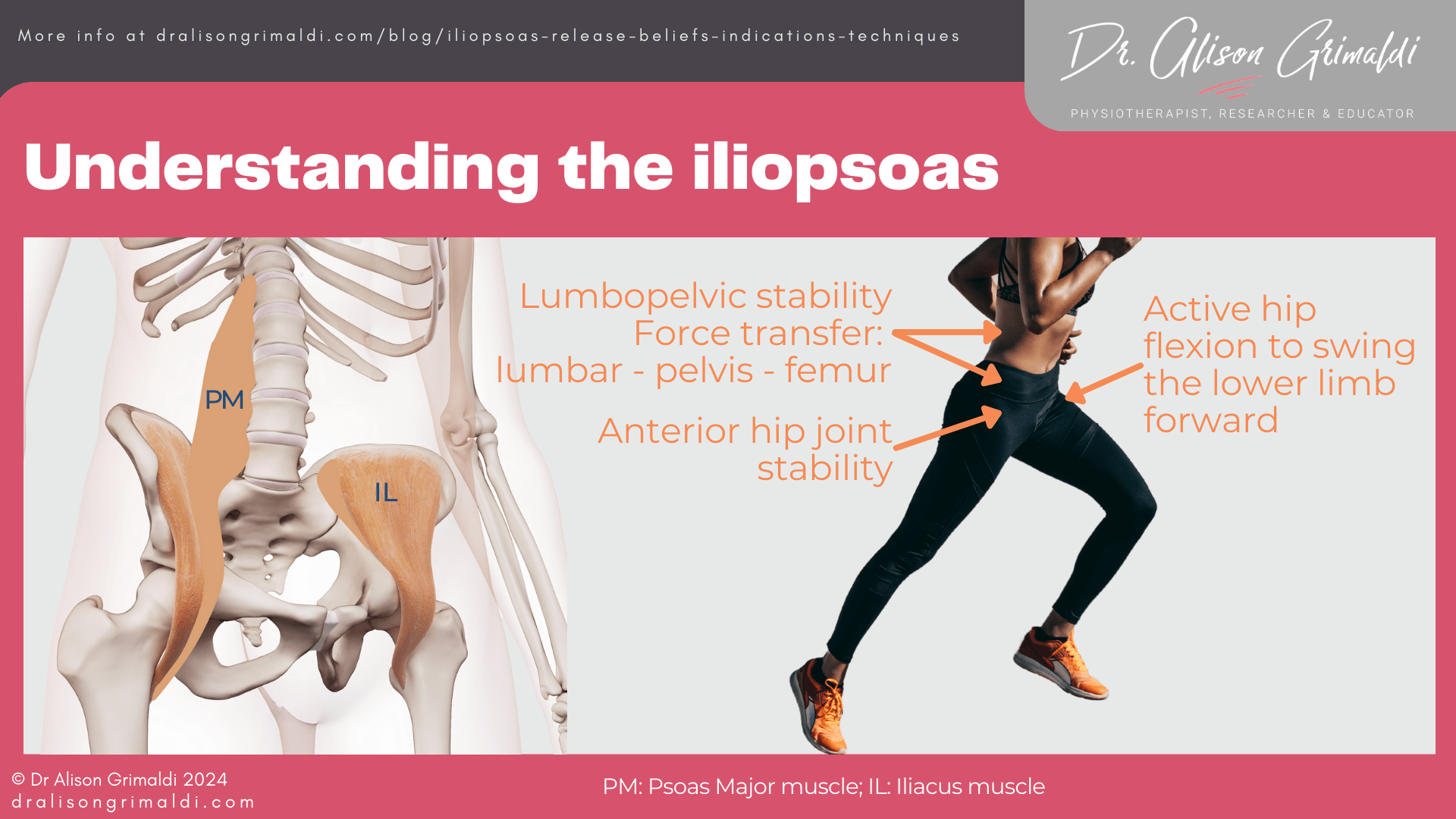

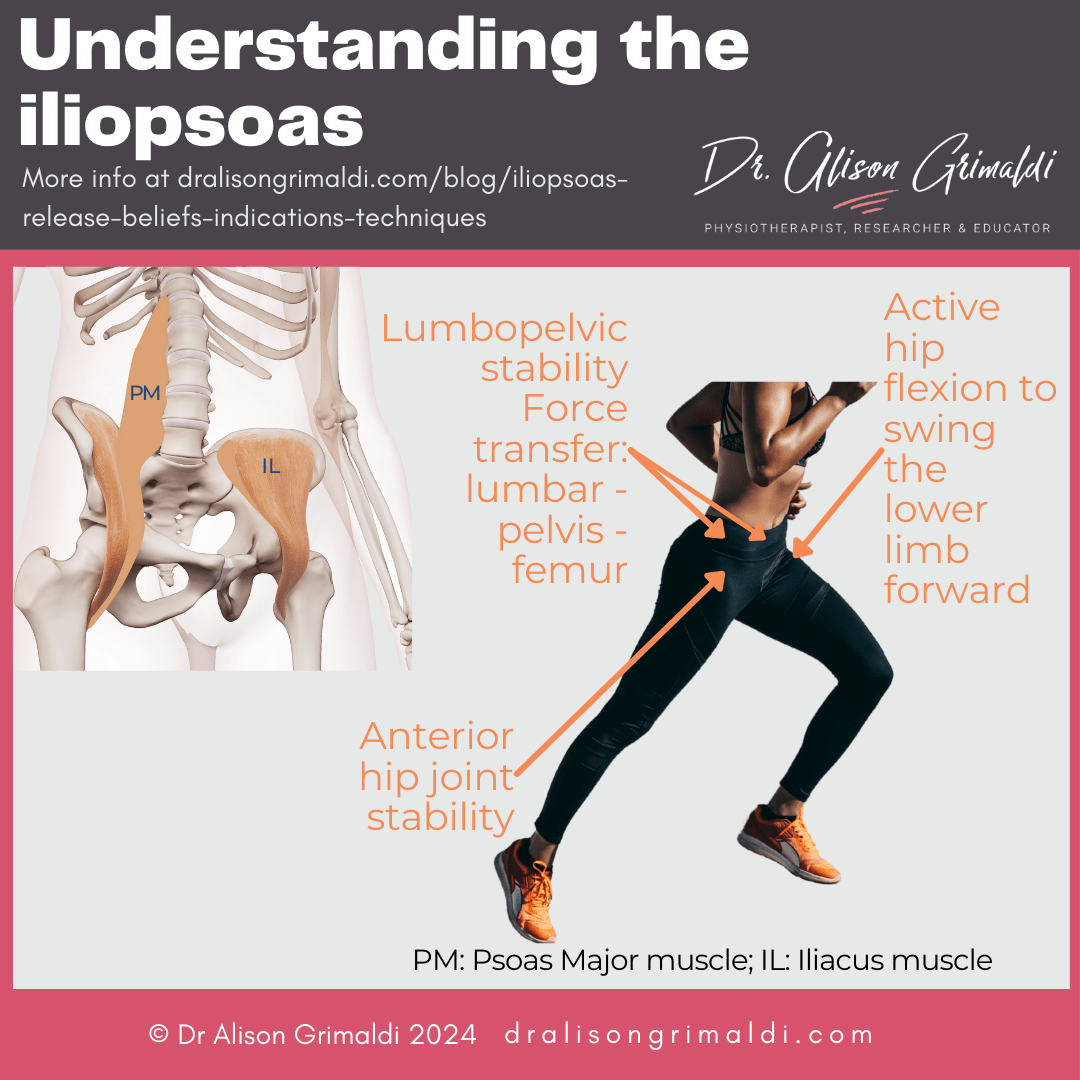

The iliopsoas muscle consists of the iliacus and psoas major muscle bellies that converge primarily into a common tendon inserting onto the lesser trochanter of the proximal femur. The psoas major muscle sits like a dynamic cylinder attached to the anterolateral aspect of the lumbar spine, originating from T12-L4 vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs and transverse processes of L1-L5 vertebrae.

The iliacus muscle belly originates from the iliac fossa – the internal surface of the ilium. The iliacus and psoas major (iliopsoas) exit the pelvis together beneath the inguinal ligament, through the psoas valley or psoas groove. The muscular iliacus belly sits directly anterior to the hip joint – the anterior acetabulum, acetabular labrum, femoral head and capsule, separated from it by the large iliopsoas bursa. The psoas major is primarily a tendon, with low muscle volume at the level of the femoral head, sitting deep and medial relative to the iliacus.

Function of the iliopsoas muscle

The iliopsoas is well known as our primary hip flexor – lifting the thigh forward for locomotion and other dynamic functions. This muscle complex also has other important functions.

In gait, the iliopsoas creates the forward momentum to lift and swing the swing-side leg through. The stance-side psoas major is thought to transfer energy through the pelvis, helping to control the trunk and pelvis on the femur, and even assisting in lumbopelvic rotation.1

Iliopsoas also plays an important role in dynamic stability of the anterior hip joint.2,3 For some with reduced passive stability mechanisms (acetabular dysplasia, capsuloligamentous laxity or deficiency), the iliopsoas may be critical for controlling anterior joint loads, particularly as the hip moves into extension e.g., at end stance phase. Iliacus also crosses the sacroiliac joint anteriorly, with intimate connections with the ventral sacroiliac ligaments, suggesting a role supporting the sacroiliac joint.

Psoas major helps support the lumbar spine, providing stability through dynamic compression.4 It is the only muscular structure attaching to the anterior surfaces of the lumbar vertebral column, working together with the posterior paraspinal musculature, abdominal wall, pelvic floor, diaphragm and intra-abdominal pressure to transfer load across the lumbar spine.

Would you like to learn more about the iliopsoas?

My Anterior Hip and Groin Pain online course is for you! Built in an easy to consume layout, learn in your own time, from the comfort of your own home. Discover joint related pain and bony impingement, soft tissue related pain, referred and nerve related pain & lots more! Explore this course today, and help more patients!

Reported indications for iliopsoas release or surgical iliopsoas tenotomy

Why would we then want to ‘release’ this important muscle?

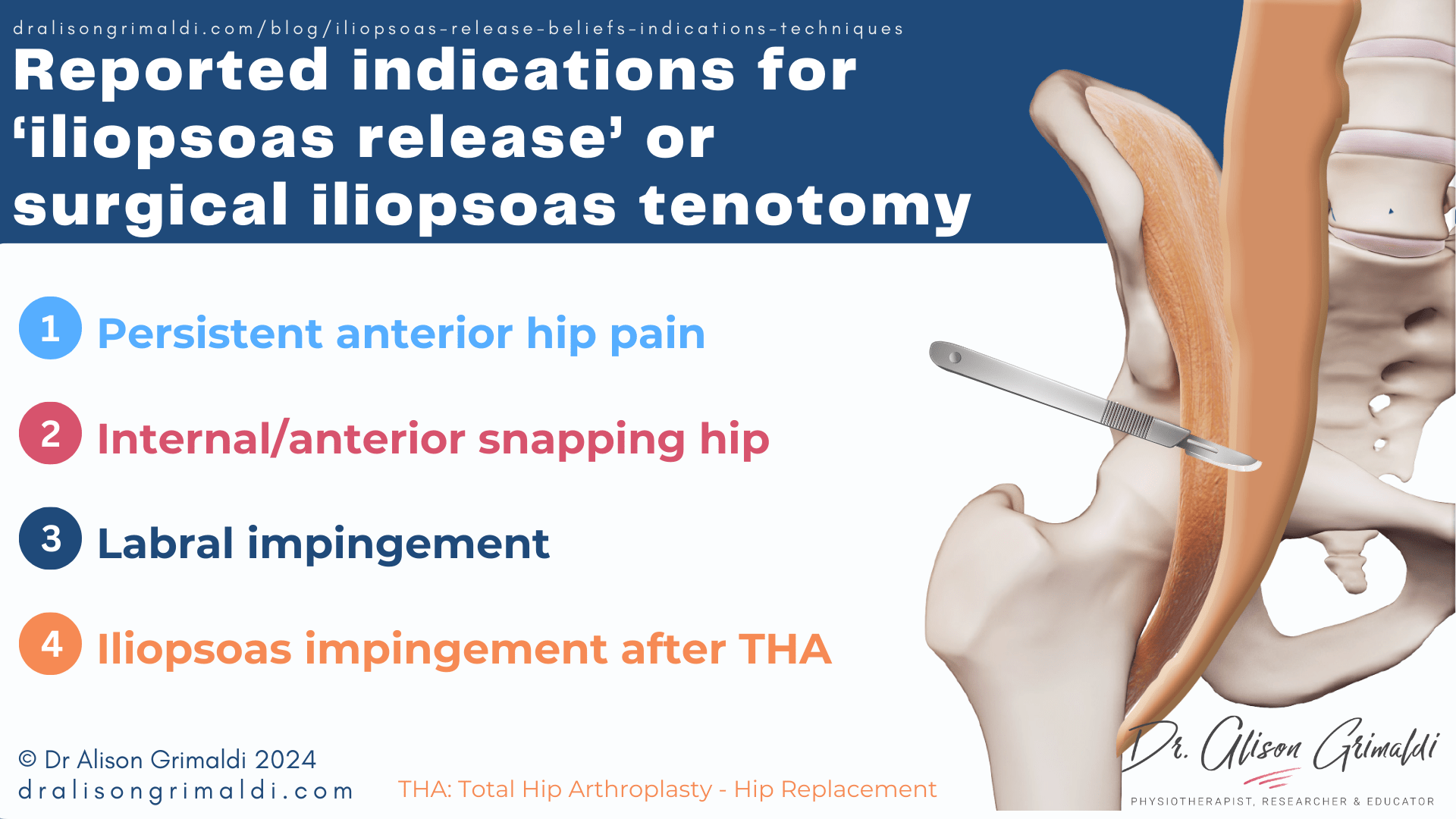

The most common indications cited for iliopsoas release or surgical iliopsoas tenotomy include:

- Presence of anterior hip or groin pain, particularly persistent pain

- Internal Coxa Saltans – Anterior Snapping Hip

- Iliopsoas impingement of the acetabular labrum

- Iliopsoas impingement following total hip arthroplasty (hip replacement)

Let’s look in a little more detail at each of these indications.

Iliopsoas release for persistent anterior hip or groin pain

When pain is experienced at the front of the hip – midway along the groin crease, there is a common assumption that the pain must be related to misbehaving hip flexors - the iliopsoas or psoas muscles in particular. It might be referred to as psoas syndrome or iliopsoas syndrome – unhelpful and uninformative terms – syndrome simply meaning a group of symptoms, in this case referring to assumed pain and tightness/overactivity of the iliopsoas.

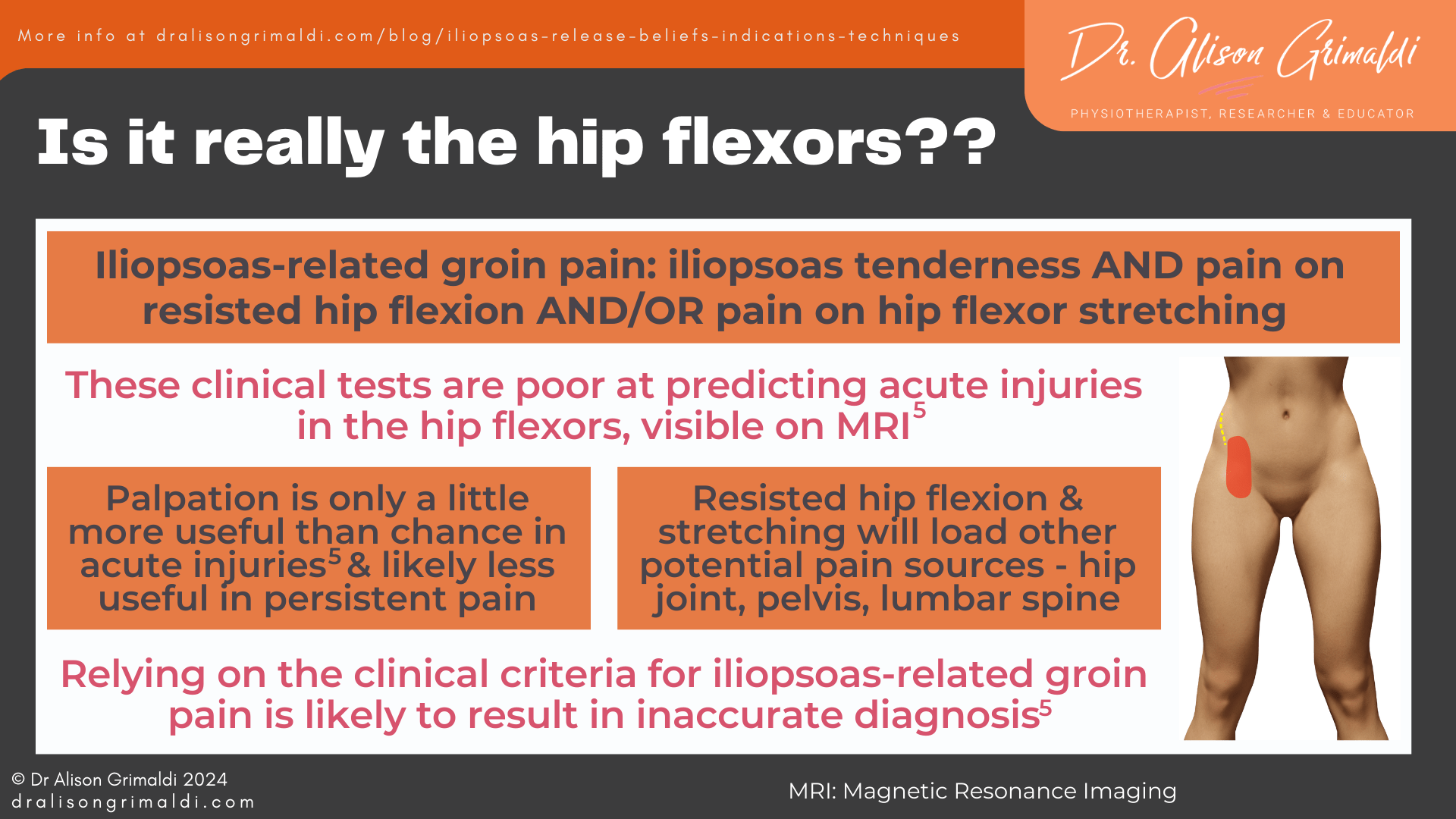

Pain related to the iliopsoas may also be referred to as Iliopsoas-related groin pain – included as one of the ‘groin pain clinical entities’.5 Iliopsoas-related groin pain is diagnosed on the basis of ‘iliopsoas tenderness, more likely if there is pain on resisted hip flexion and/or pain on hip flexor stretching.’6

Iliopsoas-related groin pain has been reported to be the second most common source of groin pain, with Hölmich’s initial paper on the ‘clinical entities of groin pain’ reporting 35% of 207 athletes had iliopsoas-related groin pain as their primary clinical entity.7 Hölmich also noted that iliopsoas-related groin pain was the most common secondary clinical entity, occurring commonly together with adductor related groin pain. A more recent study of 100 athletes reported that 31% had iliopsoas-related groin pain, according to the Doha Agreement clinical entities definition, although only 2 of these athletes were diagnosed with isolated iliopsoas-related groin pain.8

But how accurate is this clinical entity diagnosis of iliopsoas-related groin pain, diagnosed through palpation primarily, and supported by pain on resisted hip flexion and/or pain on stretching? Andreas Serner’s study revealed that hip flexor clinical tests were poor at predicting acute injuries in the hip flexors, visible on MRI.9 Palpation provided the best probability of an accurate diagnosis, but this was not much better than chance. These authors concluded that using the clinical criteria for iliopsoas-related groin pain ‘is likely to result in inaccurate classification of acute injuries in this area’. If this is the case in acute injuries, the accuracy is likely to diminish even further with persistent hip pain.

What the research tells us, is that tenderness on palpation at the front of the hip, together with pain reproduction on hip flexor contraction and/or stretch, is commonly present in those with anterior hip and groin pain but doesn’t necessarily reflect injury or pathology of the iliopsoas itself.

Such clinical signs are common in those with other primary conditions, for example, adductor-related groin pain and joint conditions, such as acetabular dysplasia. ‘Iliopsoas-related pain’ diagnosed through palpation and pain on hip flexor stretching in Thomas Test, was the most common muscle-tendon entity detected in a group of 100 young adults with hip pain related to acetabular dysplasia – positive tests reported in 56 participants.10

But how do we know those clinical signs are related to some form of pathology or dysfunction in the iliopsoas? Anterior hip pain generated by stretching the hip into extension, loads many structures, including the anterior adductors (pain location should be different though) and the underlying hip joint. These structures will also be loaded by resisted hip flexion.

Should ‘iliopsoas release’ then be applied liberally for anyone presenting with ‘iliopsoas-related groin pain’? This is not a clear diagnosis and is often a group of secondary signs related to a primary condition such as adductor-related groin pain or hip-joint related pain. Then we need to ask, are ‘release’ or stretching techniques suitable for the primary condition?

Stretching is not recommended for adductor-related groin pain (or iliopsoas-related groin pain), is unlikely to be helpful for those with reduced hip joint stability associated with acetabular dysplasia and may even worsen outcomes.

I am not suggesting that the iliopsoas is never a source of pain. The iliopsoas is often exposed to overload, and this may become painful but making an isolated diagnosis based solely on the clinical definition of ‘iliopsoas-related groin pain’ and applying ‘iliopsoas release’ strategies as a treatment approach is inappropriate and may even be harmful.

This is particularly concerning if the iliopsoas release technique selected is a surgical intervention involving irreversible partial detachment of the iliopsoas at the anterior hip. We will cover other indications for surgical release of the iliopsoas tendon (iliopsoas tenotomy), but often surgical release is offered purely on the basis of persistent anterior hip pain, commonly after a ‘failed’ arthroscopy or total hip arthroplasty. Corticosteroid injection is usually offered first and if pain persists, iliopsoas release may be performed, far too often in my opinion, in young-middle aged individuals who wish to return to higher activity levels.

Like to learn more about the Iliopsoas, and management of Anterior Hip and Groin Pain?

In this course, you'll receive detailed information on pathoaetiology, assessment and management of hip joint related pain and other soft tissue and nerve related conditions. To learn more, take the anterior hip and groin pain online course, or join me in an online or practical anterior hip and groin pain workshop.

Iliopsoas release for Coxa saltans – Anterior snapping hip

Another common reason for iliopsoas release is snapping of the iliopsoas tendon at the front of the hip – referred to variably as internal coxa saltans, internal snapping hip, anterior snapping hip, iliopsoas snapping or snapping hip syndrome. While there remains contention over the cause of this snapping, a common rationale for surgical iliopsoas release is that ‘the iliopsoas is tight’. Yet there is no evidence that I have been able to locate that anyone has actually performed length testing in a cohort with painful snapping hip.

The population where snapping hip is most common is in classical ballet dancers, where at least 60% had been reported to have an iliopsoas snap.11 If you think about the typical ballet athlete, they certainly tend to be on the mobile side and in clinic, snapping hip appears to be much more common in those with long iliopsoas, not short. This population is also more likely to have global hypermobility and bony features that enhance range of motion but reduce stability, such as reduced acetabular coverage.

So, for many with anterior snapping hip, 1. They are NOT tight, and 2. They are more likely to have reduced passive stability mechanisms. Surgical iliopsoas release in such a situation, may put the patient’s hip at risk (more on that in my next blog), and manual ‘release’ or stretching also would not have a clear rationale.

One more recent rationale for surgical iliopsoas release to internal coxa saltans, is the presence of bifid or trifid tendons.12 The snapping may then be related to the tendon slips snapping around each other. However, the snapping may persist if the bifid tendon is surgically released, suggesting this is not the only mechanism.

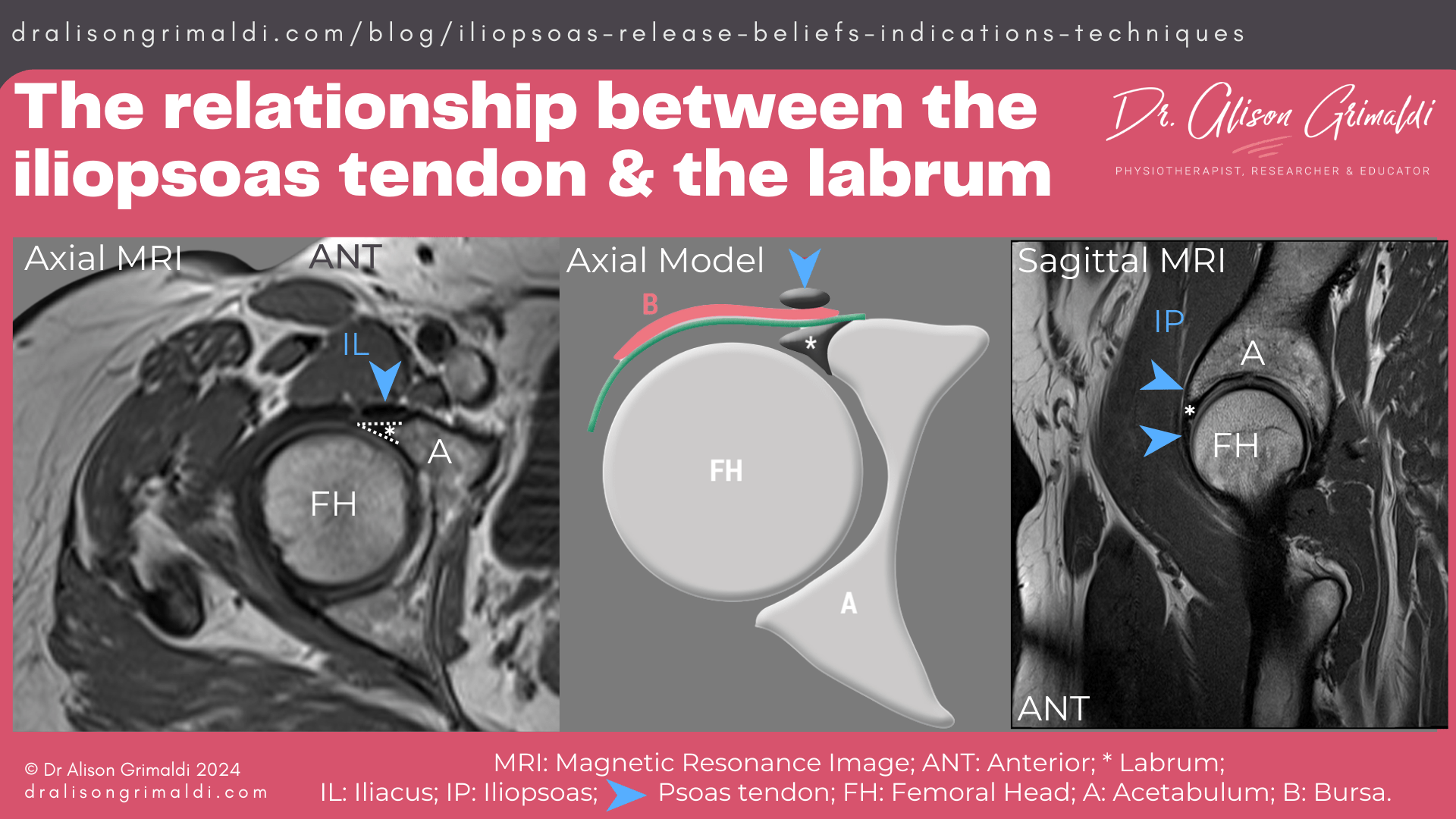

Iliopsoas release for labral impingement

In 2011, Domb and colleagues’ seminal paper announced a whole new reason for surgical release of the iliopsoas tendon: ’Iliopsoas impingement: A newly identified cause of labral pathology in the hip.’13 While the revelation of the close relationship between the iliopsoas tendon and the acetabular labrum at the 3 o’clock (direct anterior) location was interesting, I must say, my heart sank when I read the discussion that jumped straight to the need for iliopsoas tenotomy.

All of a sudden, the orthopaedic community appeared to have an even better reason to release this important tendon - a tendon that must not only be causing persistent anterior hip pain and snapping, but also damaging the labrum! The rates of iliopsoas tenotomy certainly seemed to experience a rise around this time, with arthroscopists learning that they could successfully release the tendon from within the central compartment.

Iliopsoas tenotomy for iliopsoas impingement following total hip arthroplasty

The final indication for iliopsoas tenotomy is the one with the strongest rationale, and that is for iliopsoas impingement following total hip arthroplasty (hip replacement), although this still appears to be performed excessively. I have written a whole blog post on persistent anterior hip pain related to iliopsoas impingement against the acetabular cup following surgery, so you might like to read more about it in that blog.

In short, the issue is related to impingement of the iliopsoas tendon against the prosthetic cup, primarily if it extends out further than the native bone. This is most likely to occur in those who had a dysplastic acetabulum or quite a deep psoas groove prior to surgery (not enough bone anteriorly to cover the new prosthesis) or due to malpositioning/orientation of the acetabular cup.

Unfortunately, this situation can lead to significant pain and disability following total hip replacement.

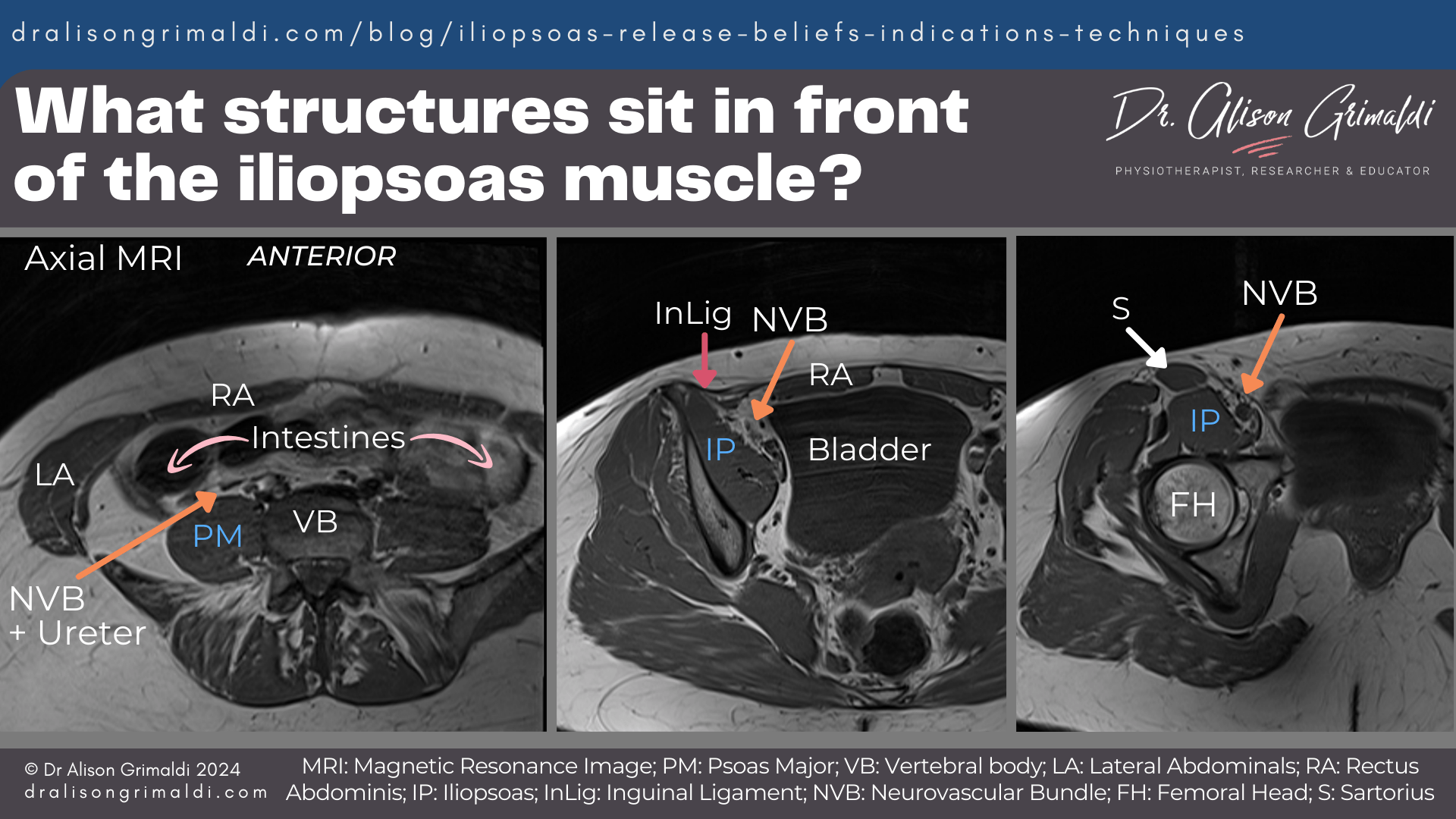

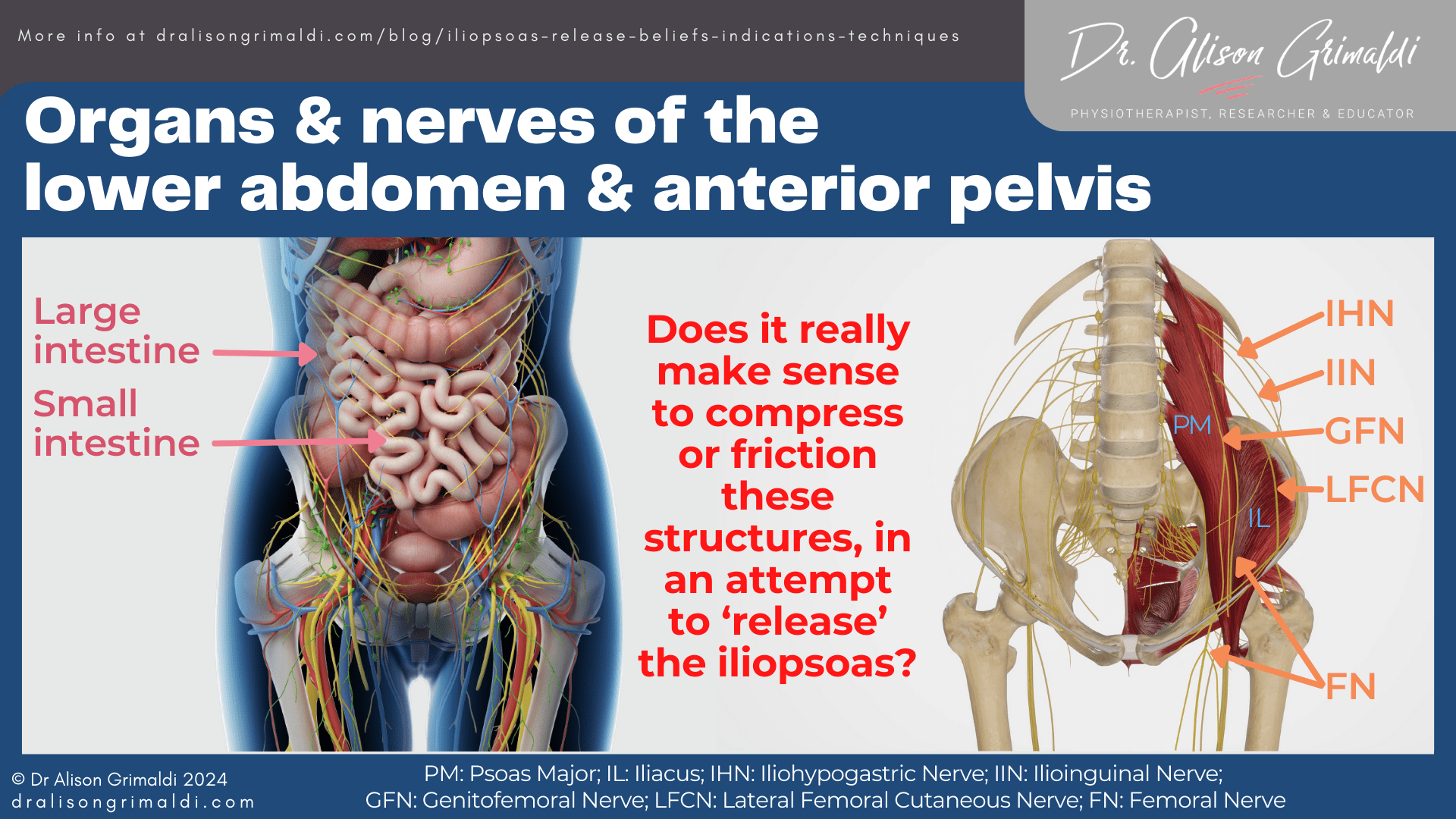

Accessing the iliopsoas – anatomical relationships

Before we talk about manual therapy and surgical techniques, let’s first consider the anatomical relationships between the iliopsoas and surrounding structures. Just how easy is it to access manually or surgically?

In the lower abdomen, anterior to the psoas muscle we have the intestines, the ureters on their pathway to the bladder, and neurovascular structures. The aorta travelling down the left anterolateral aspect of the spine with the psoas major muscle, bifurcates into the common iliac arteries at around the L4-5 level. The arteries are of course accompanied by veins and lymph vessels.

Understand the Iliopsoas better!

This Anterior Hip and Groin Pain online course can help you help more people with Anterior Hip & Groin Pain! Explore joint related pain and bony impingement, soft tissue related pain (including iliopsoas related pain), referred and nerve related pain & lots more! Signup today!

Nerves that sit within or anterior to the iliopsoas muscle bellies

The psoas major muscle is intimately associated with nerve structures. The lumbar plexus is embedded within the psoas major muscle, and its branches emerge from it.

The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves run between the layers of the abdominal wall before travelling just above or through the inguinal canal respectively.

The genitofemoral nerve exits the psoas major ventrally, travelling along the anterior surface of the psoas major to the inguinal, genital and femoral regions.

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve emerges from the lateral aspect of the psoas major and travels laterally around the iliac fossa on the anterior surface of the iliacus muscle, deep to the iliac fascia. When it reaches the anterior pelvis, it exits either through or under the inguinal ligament, just inside the Anterior Superior Iliac Spine (ASIS), before serving the lateral thigh.

The femoral nerve forms within the psoas, exits laterally, travels down the lateral aspect of the psoas major, before becoming sandwiched between the iliacus and psoas muscle bellies, exiting beneath the inguinal ligament and joining the femoral artery, vein and deep inguinal lymph nodes and vessels in the femoral triangle.

Common techniques used for iliopsoas release

With this anatomy in mind, let’s now look at techniques used for iliopsoas release. I tried a search for ‘iliopsoas release techniques’ in google to see what results would be returned. Google produced circa 500, 000 results!! Most of these are some form of manual therapy or stretching techniques. Then there are of course the ‘true’ surgical release techniques.

Non-surgical ‘iliopsoas release’ techniques

Manual therapy techniques generally target either the psoas or iliacus muscle bellies, with the majority online appearing to target the psoas muscle belly. Techniques vary from manual techniques using the therapists’ thumbs, fingers, fists or even elbows! Then there are the instrumented techniques employing tools such as smooth or spikey balls, foam rollers and other custom devices such as the Hip Hook or Pso-Rite tools.

All techniques involve an anterior approach, pushing deep inside the ASIS (iliacus) or abdomen, either side of the spine (psoas), applying sustained pressure or travelling along the line of the muscle belly.

Such techniques and tools are somewhat concerning if we consider the anatomy and structures that sit between the anterior abdominal wall/inguinal region and the iliopsoas muscle bellies.

Various stretching techniques are also regularly applied or recommended for ‘iliopsoas related groin pain’, snapping hip and iliopsoas impingement.

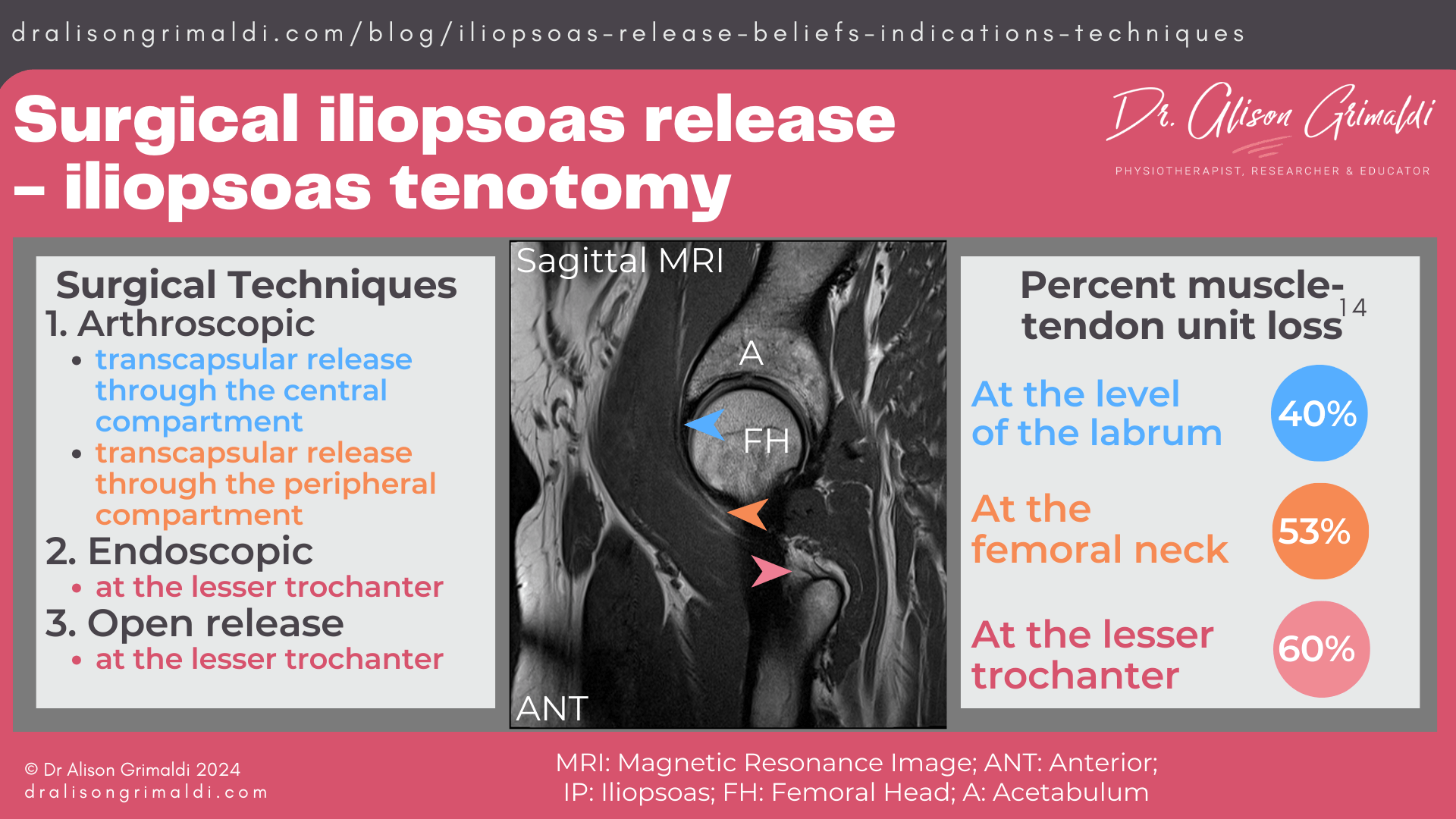

Surgical iliopsoas release – iliopsoas tenotomy

The popularity and prevalence of surgical iliopsoas release appears to vary, just like rehab approaches. There certainly seemed to be an increase that corresponded with the increase in arthroscopic surgery, technical skills and surgeon confidence in performing these techniques from within the hip joint.

We may also be seeing an increase in iliopsoas release following total hip arthroplasty, due to higher use of larger dual-mobility implants, one of the factors increasing the risk of post-operative iliopsoas impingement.

Surgical iliopsoas release is referred to variably as iliopsoas fractional lengthening, iliopsoas tenotomy or simply iliopsoas release. There are a number of different techniques and locations in which the iliopsoas can be released, with differing impacts on function and complications.

Surgical techniques for iliopsoas release

- Open release

- Iliopsoas release was traditionally performed via open surgery. Some surgeons still use an open technique, but most now prefer an arthroscopic or endoscopic technique due to lower complication rates. Open release is generally performed at the level of the lesser trochanter.

- Arthroscopic release

- Transcapsular release accessed through the central compartment.

Arthroscopic techniques require a transcapsular approach – this means that the surgeon needs to perform a capsulotomy, cutting open the capsule from inside the joint to access the overlying iliopsoas tendon. This is commonly done from the central compartment, approaching from the space between the femoral head and acetabulum. A central compartment release is performed usually at the level of the labrum. - Transcapsular release through the peripheral compartment.

A peripheral compartment release still requires a transcapsular approach, but the capsular opening is at the level of the femoral neck, outside the actual femoroacetabular joint (central compartment). The tendon is therefore released a little more distally.

- Transcapsular release accessed through the central compartment.

- Endoscopic release

An endoscopic iliopsoas release is a minimally invasive technique where the iliopsoas is generally released at the lesser trochanter. Surgeons do not use large open incisions, instead using small portals and arthroscopy tools. As they are not within the joint (arthro), the procedure is an endoscopic, not an arthroscopic technique.

Location and proportion of iliopsoas release

The percentage of the iliopsoas muscle-tendon unit that is released depends on the location of the iliopsoas release. Surgical release is focused on the tendon, but the distal portion of the iliopsoas is comprised of both tendon and muscle, right down to its distal attachment. The muscular contribution gradually reduces, and the relative tendon contribution increases to the iliopsoas insertion.

At the level of the labrum, the tendon comprises 40% of the muscle-tendon unit.14 Therefore, there will be a 40% loss of iliopsoas tissue when released at this level. An arthroscopic transcapsular release from the central compartment, will most commonly be performed at the level of the labrum.

At the femoral neck, there will be a loss of around 53%.14 This is the location of tendon release during an arthroscopic transcapsular release through the peripheral compartment.

In open and endoscopic procedures, the location of release is usually at the lesser trochanter, where 60% of the muscle-tendon unit will be released. 14 The closer to the insertion that the release is performed, the greater the loss of the muscle-tendon unit but there should theoretically be at least 40% of the musculotendinous unit attached.

I say ‘theoretically’, because I have seen many patients post iliopsoas release who have minimal to no iliopsoas muscle belly evident at the anterior hip on ultrasound assessment. It seems that some people may have a larger tendon composition than that suggested in available cadaveric studies, or some surgeons may also release some of the muscular tissue. Alternatively, it could be possible that in the absence of the strong tendon, the muscular tissue may become further damaged by unaccustomed load, resulting in greater ‘release’ than intended.

Now you should have a good understanding of iliopsoas release beliefs, indications and techniques. Make sure you keep an eye out for next month’s blog where I will be presenting the case against iliopsoas release. I’ll be discussing the frequent lack of understanding of symptoms and underlying mechanisms, the efficacy of iliopsoas release, potential risks, complications and long term sequalae of iliopsoas release, and alternative approaches to addressing iliopsoas issues. See you then!

And if you'd like to learn more about anterior hip and groin pain conditions and how to best assess and manage them, join me in a live practical or online workshop. My Anterior Hip & Groin Pain Workshops include the Anterior Hip & Groin Pain online course as pre-reading (listening) before the live events. Would love to see you at an upcoming event.

Like to learn more about the Iliopsoas, and management of Anterior Hip and Groin Pain?

In this course, you'll receive detailed information on pathoaetiology, assessment and management of hip joint related pain and other soft tissue and nerve related conditions. To learn more, take the anterior hip and groin pain online course, or join me in an online or practical anterior hip and groin pain workshop.

This blog was written by Dr Alison Grimaldi

Dr Alison Grimaldi is a physiotherapist, researcher and educator with over 30 years of clinical experience. She has completed a Bachelor of Physiotherapy, a Masters of Sports Physiotherapy and a PhD, with her doctorate topic in the hip region. Dr Grimaldi is Practice Principal of PhysioTec Physiotherapy in Brisbane and an Adjunct Senior Research Fellow at the University of Queensland. She runs a global Hip Academy and has presented over 100 workshops around the world.

Check Out Some More Relevant Blogs

- Sanaka K, Hashimoto K, Kurosawa D, Murakami E, Ozawa H, Takahashi K, Onoki T, Aizawa T. The psoas major muscle is essential for bipedal walking - An analysis using a novel upright bipedal-walking android model. Gait Posture. 2022 May;94:15-18. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2022.02.018. Epub 2022 Feb 17. PMID: 35193084.

- Retchford TH, Crossley KM, Grimaldi A, Kemp JL, Cowan SM. Can local muscles augment stability in the hip? A narrative literature review. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2013 Mar;13(1):1-12. PMID: 23445909.

- Hirase T, Mallett J, Barter LE, Dong D, McCulloch PC, Harris JD. Is the Iliopsoas a Femoral Head Stabilizer? A Systematic Review. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2020 Nov 17;2(6):e847-e853. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2020.06.006. PMID: 33364616; PMCID: PMC7754519.

- Penning L. Psoas muscle and lumbar spine stability: a concept uniting existing controversies. Critical review and hypothesis. Eur Spine J. 2000 Dec;9(6):577-85. doi: 10.1007/s005860000184. PMID: 11189930; PMCID: PMC3611424.

- Weir A, Brukner P, Delahunt E, et al. Doha agreement meeting on terminology and definitions in groin pain in athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2015 Jun;49(12):768-74. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094869. PMID: 26031643; PMCID: PMC4484366.

- Heijboer WMP, Weir A, Vuckovic Z, Fullam K, Tol JL, Delahunt E, Serner A. Inter-examiner reliability of the Doha agreement meeting classification system of groin pain in male athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2023 Feb;33(2):189-196. doi: 10.1111/sms.14248. Epub 2022 Oct 29. PMID: 36259124; PMCID: PMC10092143.

- Hölmich P. Long-standing groin pain in sportspeople falls into three primary patterns, a "clinical entity" approach: a prospective study of 207 patients. Br J Sports Med. 2007 Apr;41(4):247-52; discussion 252. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033373. Epub 2007 Jan 29. PMID: 17261557; PMCID: PMC2658954.

- Taylor R, Vuckovic Z, Mosler A, Agricola R, Otten R, Jacobsen P, Holmich P, Weir A. Multidisciplinary Assessment of 100 Athletes With Groin Pain Using the Doha Agreement: High Prevalence of Adductor-Related Groin Pain in Conjunction With Multiple Causes. Clin J Sport Med. 2018 Jul;28(4):364-369. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000469. PMID: 28654441.

- Serner A, Weir A, Tol JL, Thorborg K, Roemer F, Guermazi A, Hölmich P. Can standardised clinical examination of athletes with acute groin injuries predict the presence and location of MRI findings? Br J Sports Med. 2016 Dec;50(24):1541-1547. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096290. Epub 2016 Aug 16. PMID: 27531521.

- Jacobsen JS, Hölmich P, Thorborg K, Bolvig L, Jakobsen SS, Søballe K, Mechlenburg I. Muscle-tendon-related pain in 100 patients with hip dysplasia: prevalence and associations with self-reported hip disability and muscle strength. J Hip Preserv Surg. 2017 Nov 17;5(1):39-46. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnx041. PMID: 29423249; PMCID: PMC5798082.

- Winston P, Awan R, Cassidy JD, Bleakney RK. Clinical examination and ultrasound of self-reported snapping hip syndrome in elite ballet dancers. Am J Sports Med. 2007 Jan;35(1):118-26. doi: 10.1177/0363546506293703. Epub 2006 Oct 4. PMID: 17021311.

- Lin B, Bartlett J, Lloyd TD, Challoumas D, Brassett C, Khanduja V. Multiple iliopsoas tendons: a cadaveric study and treatment implications for internal snapping hip syndrome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2022 Jun;142(6):1147-1154. doi: 10.1007/s00402-021-04009-5. Epub 2021 Aug 4. PMID: 34347120; PMCID: PMC9110434.

- Domb BG, Shindle MK, McArthur B, Voos JE, Magennis EM, Kelly BT. Iliopsoas impingement: a newly identified cause of labral pathology in the hip. HSS J. 2011 Jul;7(2):145-50. doi: 10.1007/s11420-011-9198-z. Epub 2011 Apr 1. PMID: 22754415; PMCID: PMC3145856.

- Blomberg JR, Zellner BS, Keene JS. Cross-sectional analysis of iliopsoas muscle-tendon units at the sites of arthroscopic tenotomies: an anatomic study. Am J Sports Med. 2011 Jul;39 Suppl:58S-63S. doi: 10.1177/0363546511412162. PMID: 21709033.