Women in Pain: Sex-Based Gaps in Musculoskeletal Clinical Practice

Musculoskeletal pain remains one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, disproportionately affecting women across the lifespan. Yet, for decades, the medical and research communities have failed to adequately address the unique biological, hormonal, and psychosocial determinants of pain in women.1,2 Despite a higher prevalence of pain conditions such as fibromyalgia, migraines, osteoarthritis, and autoimmune disorders among women, clinical encounters often leave their pain dismissed, psychologised, or inadequately managed.3

GUEST POST

Huge thanks to our guest contributer for this post - Sonam Jethwa, long term Hip Academy member and a highly experienced physiotherapist. Sonam recently presented a masterclass for our membership on this topic. You can read more about Sonam at the end of this blog, and find out more about Hip Academy and our masterclasses below.

We now understand that musculoskeletal pain is neither purely mechanical nor solely the result of tissue damage. Rather, it is a complex, multidimensional experience shaped by biological, psychological, and social processes—including life transitions, healthcare interactions, and societal influences. When it comes to women, these layers reveal one undeniable truth: we are missing something big.

In this blog, I share key insights from my recent presentation and essay, arguing for a paradigm shift in how we understand and treat musculoskeletal pain in females. This shift demands that clinicians integrate female-specific biological, hormonal, and psychosocial factors into every layer of assessment, reasoning, and care.

This blog will cover the following topics:

- Sex-Based Disparities in Pain Experiences

- Gender Bias in Research and Clinical Practic

- Bridging the Gap

- Exploring female sex-specific biological and psychosocial determinants of pain

- The Influence of Sex Hormones on Pain

- Immune and Neuroendocrine Contributions to Sex Differences in Pain

- Psychosocial Determinants and Gender-Based Vulnerabilities

- Exploring female sex-specific biological and psychosocial determinants of pain

- Clinical Implications for Physiotherapy Practice

- Conclusion: Towards Equitable Musculoskeletal Practice

Sex-Based Disparities in Pain Experiences

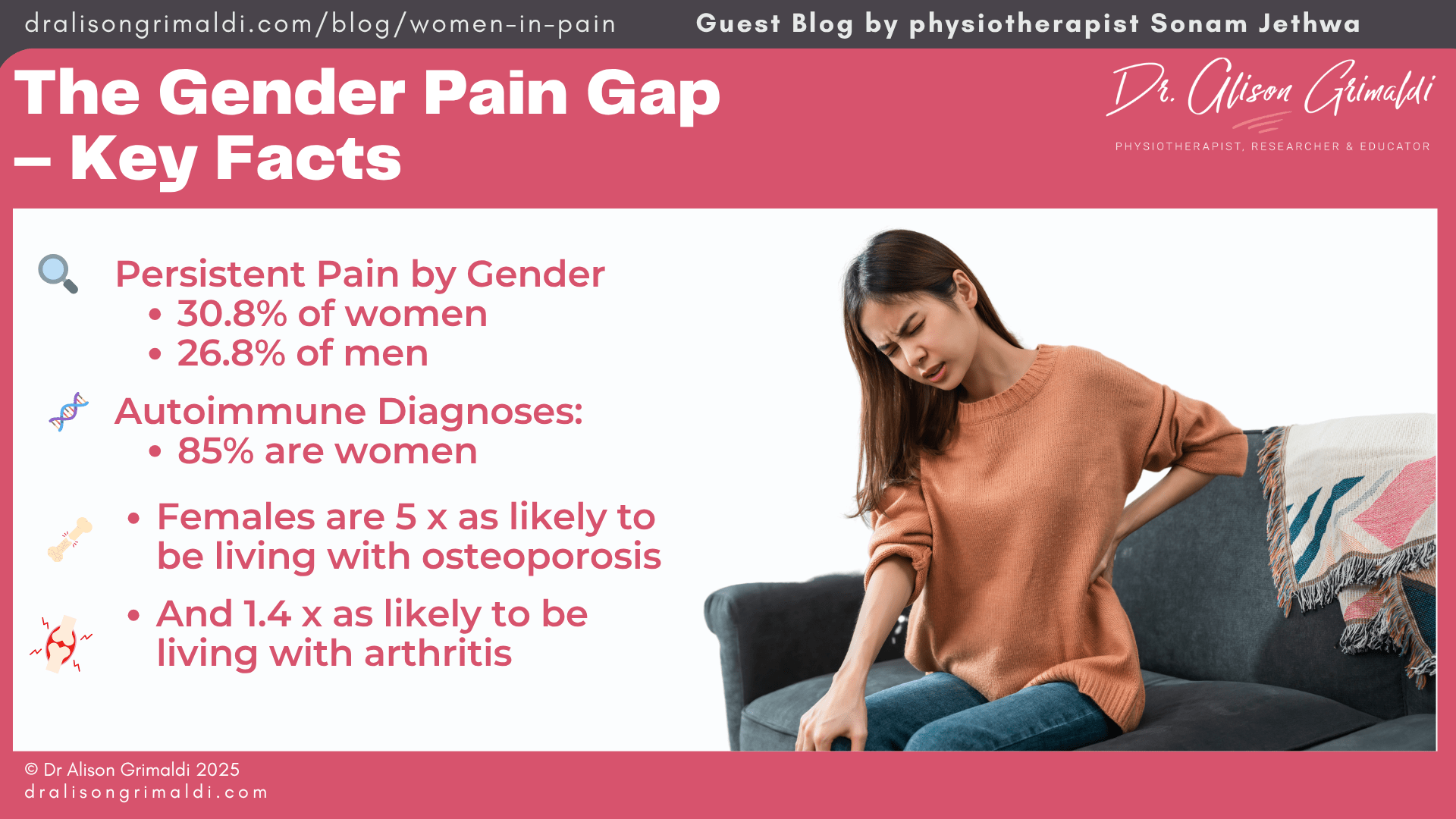

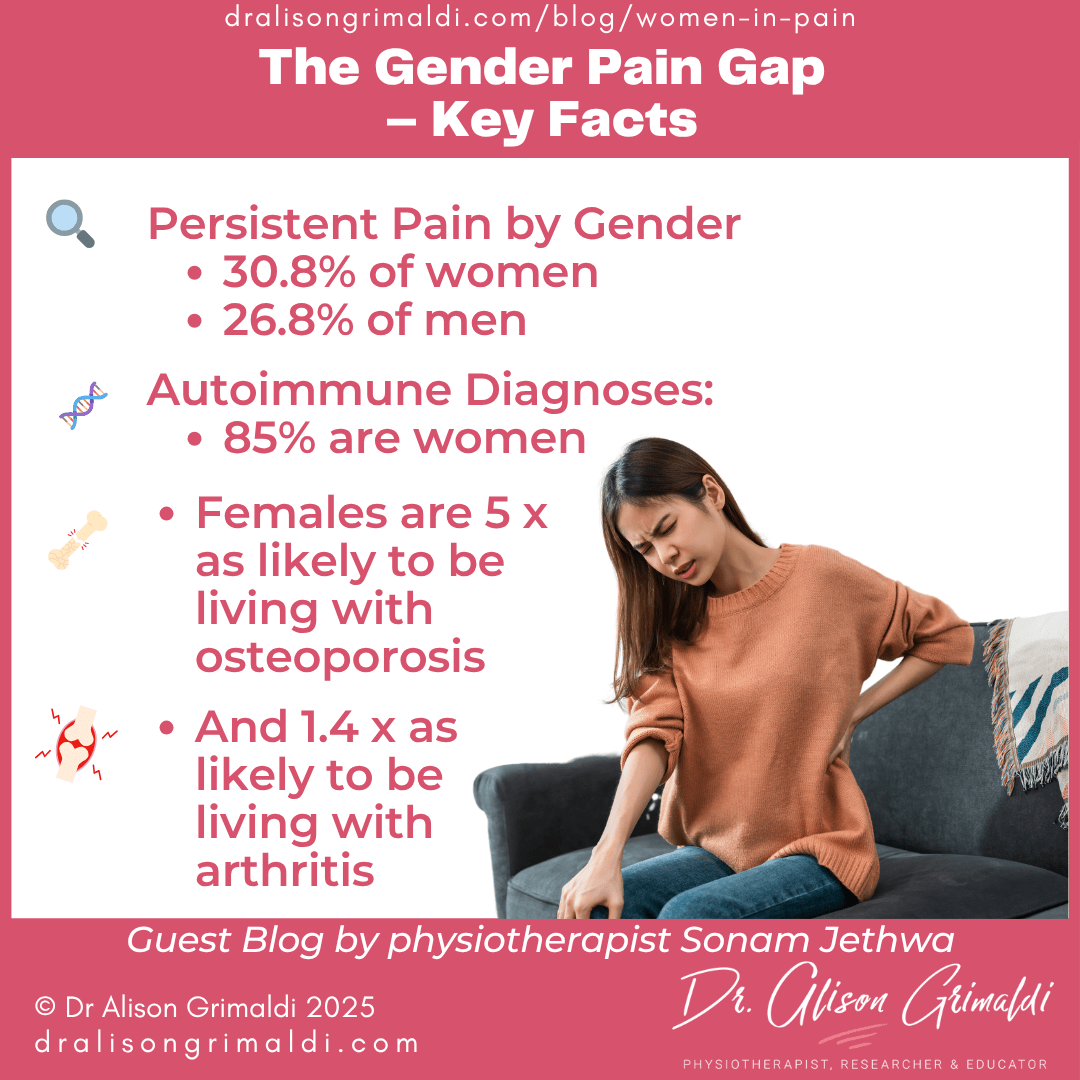

Persistent pain affects approximately 30.8% of women compared to 26.8% of men2. Research also indicates that women are five times more likely to experience osteoporosis and 1.4 times more likely to have arthritis compared to men.4 Moreover, women represent 85% of autoimmune diagnoses.5

Compounding this burden is the phenomenon of Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions (COPCs). These include fibromyalgia, endometriosis, temporomandibular disorders, vulvodynia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and migraines. COPCs are more common in female and are associated with heightened pain sensitivity, poorer functional outcomes, and increased healthcare utilisation6,7.

The Victorian Gender Pain Gap report,8,9 further highlighted that nearly one in three women experienced negative healthcare interactions related to pain. Many women reported that their concerns were dismissed, their symptoms attributed to psychological causes, or they were inappropriately referred to mental health services. These outcomes underscore the pervasive sex-based bias that persists across both clinical research and practice—manifesting through the ongoing under recognition of their pain experiences in healthcare settings.

These issues are further exacerbated in culturally and linguistically diverse populations, where communication barriers and cultural assumptions can mask legitimate pain experiences.10 Clinicians should be aware of these layered vulnerabilities when assessing and treating pain in women.

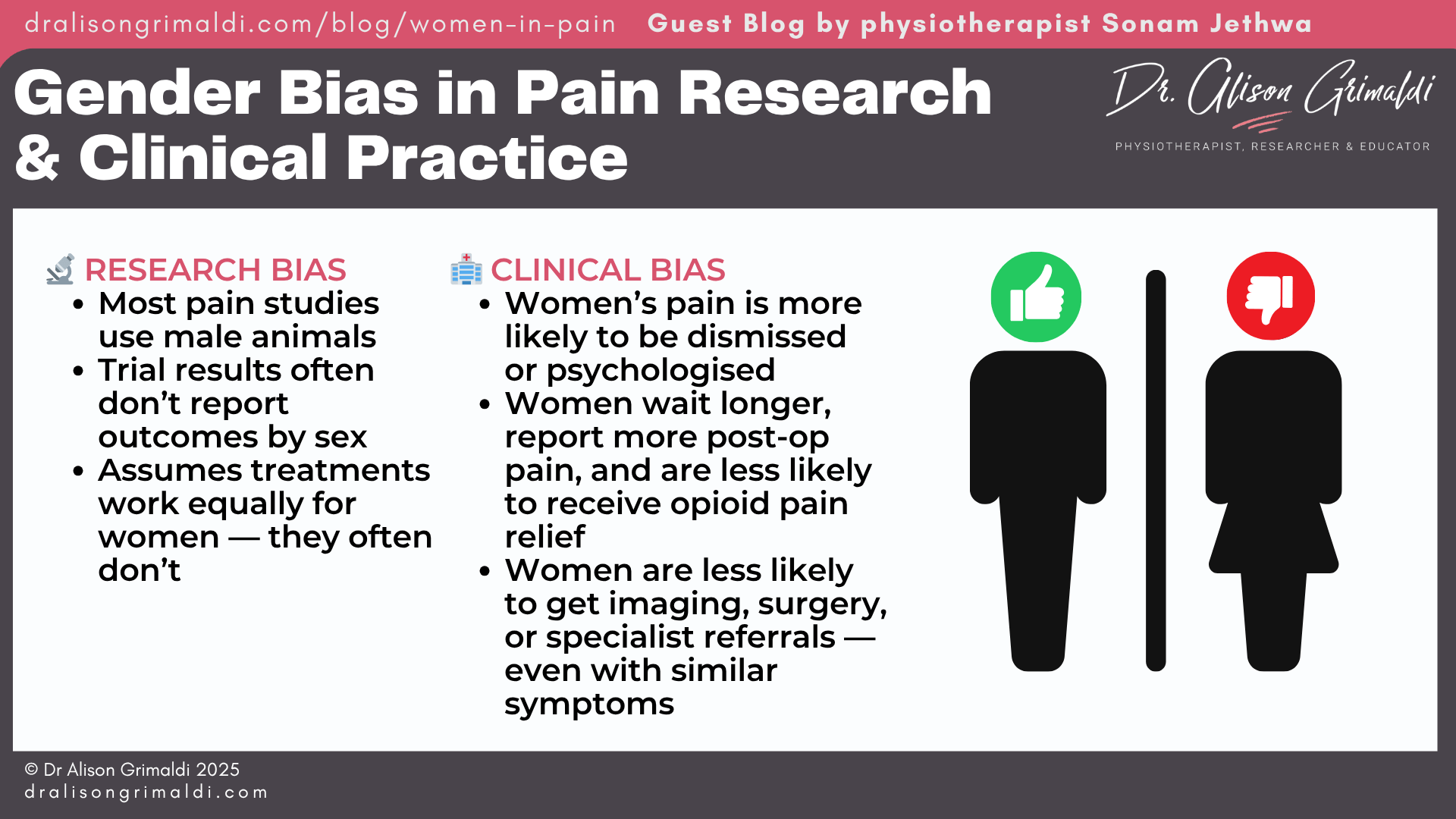

Gender Bias in Research and Clinical Practice

Historical gender biases in research and clinical settings have been well-documented.11 Preclinical studies of pain predominantly using male rodents may not account for sex-specific pain mechanisms, potentially limiting translational applicability for both sexes.12 Clinical trials often fail to adequately describe outcomes by sex, relying on the flawed assumption that treatments effective for men would also work for women, potentially resulting in serious consequences.12,13

In clinical encounters, women frequently report feeling dismissed, particularly when their symptoms do not align with traditional biomedical models.8 The literature indicates that clinicians sex bias often negatively influences pain communication, assessment, and treatment decisions during clinical encounters.12,14 Furthermore, women tend to experience longer wait times, report higher levels of post-operative pain, and are less likely to receive opioid-based analgesia compared to men.15

Multiple studies demonstrate that women with musculoskeletal conditions are less likely to receive timely imaging, surgical referral, or specialist pain input compared to men with similar clinical presentations.16,17 This disparity is influenced by implicit biases in clinical reasoning, underestimation of women’s pain reports, and structural inequities in healthcare access.

Want more? Gain access to all online hip courses, live and recorded masterclasses, Q & A sessions and Member Case sharing, and exclusive access to our entire how-to video library, ebook series and pdf resource library - diagnostic cheat sheets, condition info, management strategies & so much more.

Click here to find out how.

Bridging the Gap

Exploring female sex-specific biological and psychosocial determinants of pain

The literature reports numerous sex-specific biological mechanisms that underlie pain at both physiological and pathological levels, and these insights underscore the necessity for sex-specific management of musculoskeletal conditions.

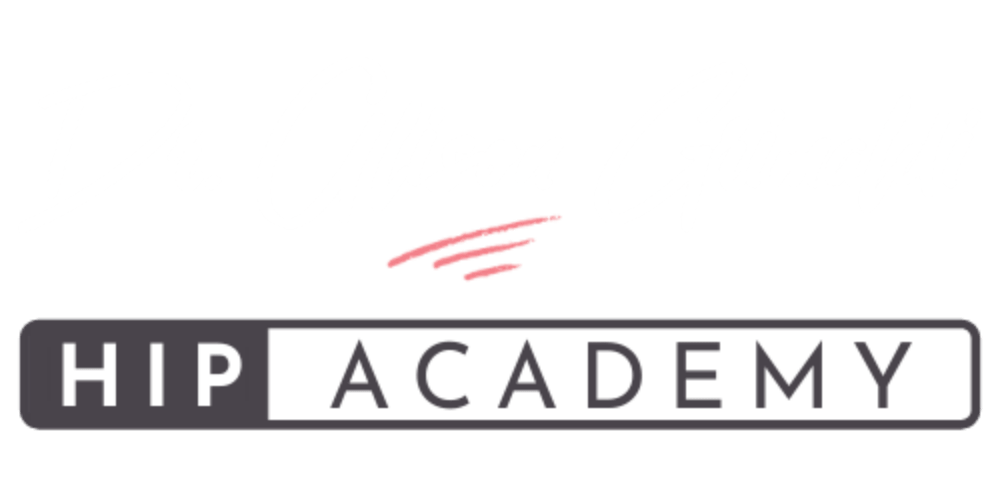

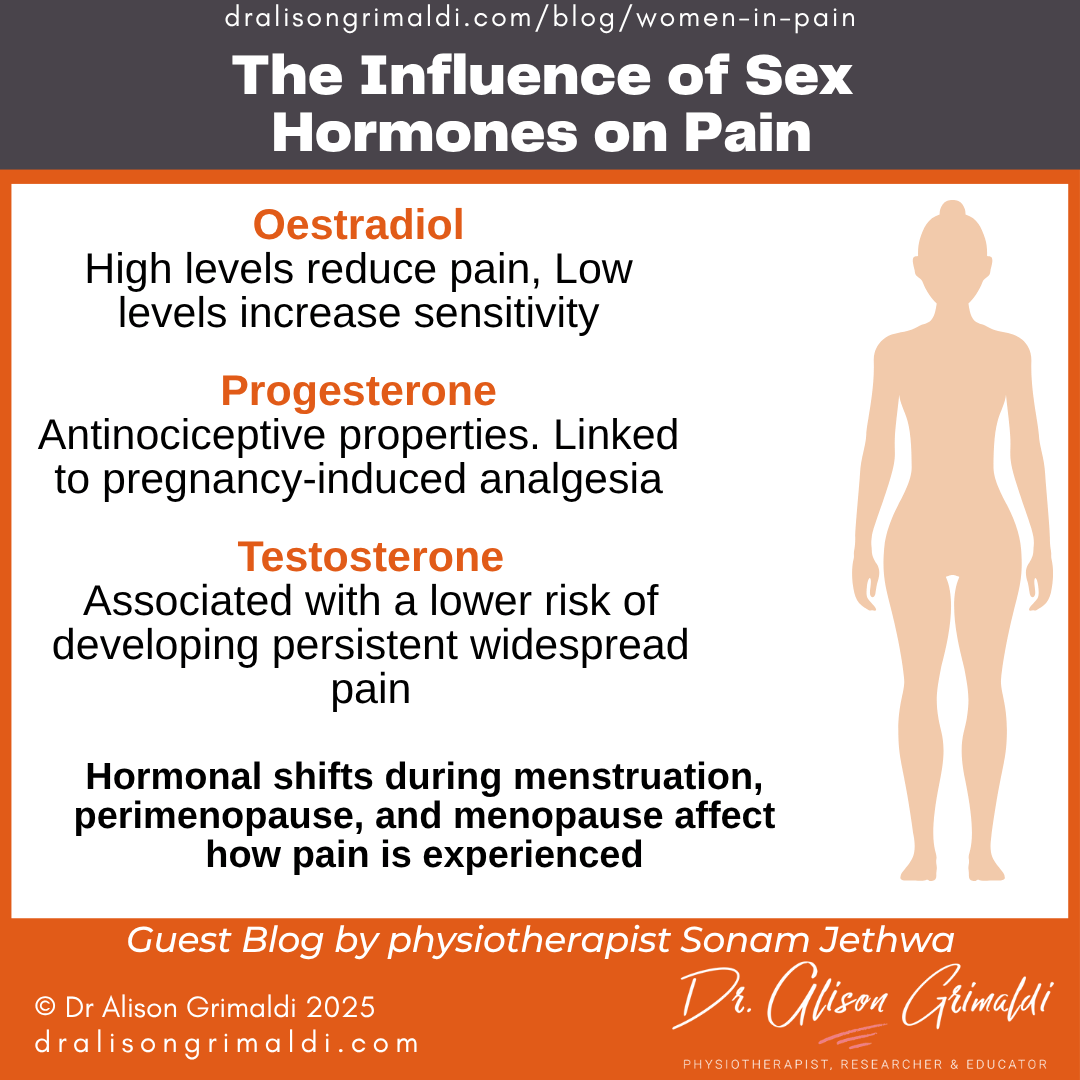

The Influence of Sex Hormones on Pain

Sex hormones significantly modulate pain perception and inflammation. Oestradiol, in particular, demonstrates complex dual roles. At high concentrations, it enhances descending inhibitory pain pathways (anti-nociceptive), while at low concentrations, it facilitates sensitisation (pro-nociceptive).1 These modulatory effects are especially evident during hormonally dynamic periods such as menstruation, perimenopause, and post-menopause.

Progesterone and testosterone also exhibit antinociceptive properties. Progesterone has been linked to pregnancy-induced analgesia, while testosterone is associated with a lower risk of developing persistent widespread pain.18

Hormonal fluctuations, whether natural or iatrogenic could influence pain thresholds, inflammatory cytokine profiles, and pain sensitivity.5 These mechanisms may help explain why many female patients present with pain that is cyclical, migratory, or resistant to standard musculoskeletal interventions.

Further, hormonal fluctuations are likely to influence not only pain perception but also tissue structure and function. For instance, variations in oestradiol levels may affect collagen synthesis, joint laxity, and tendon health.1

It is important for clinicians to assess whether pain intensifies during specific hormonal phases. Tracking symptoms across the cycle may help identify hormone-sensitive pain presentations and tailor treatment accordingly. For instance, some patients may benefit from modifying exercise loads or incorporating pacing strategies during ovulation or menstruation when symptoms are worse.

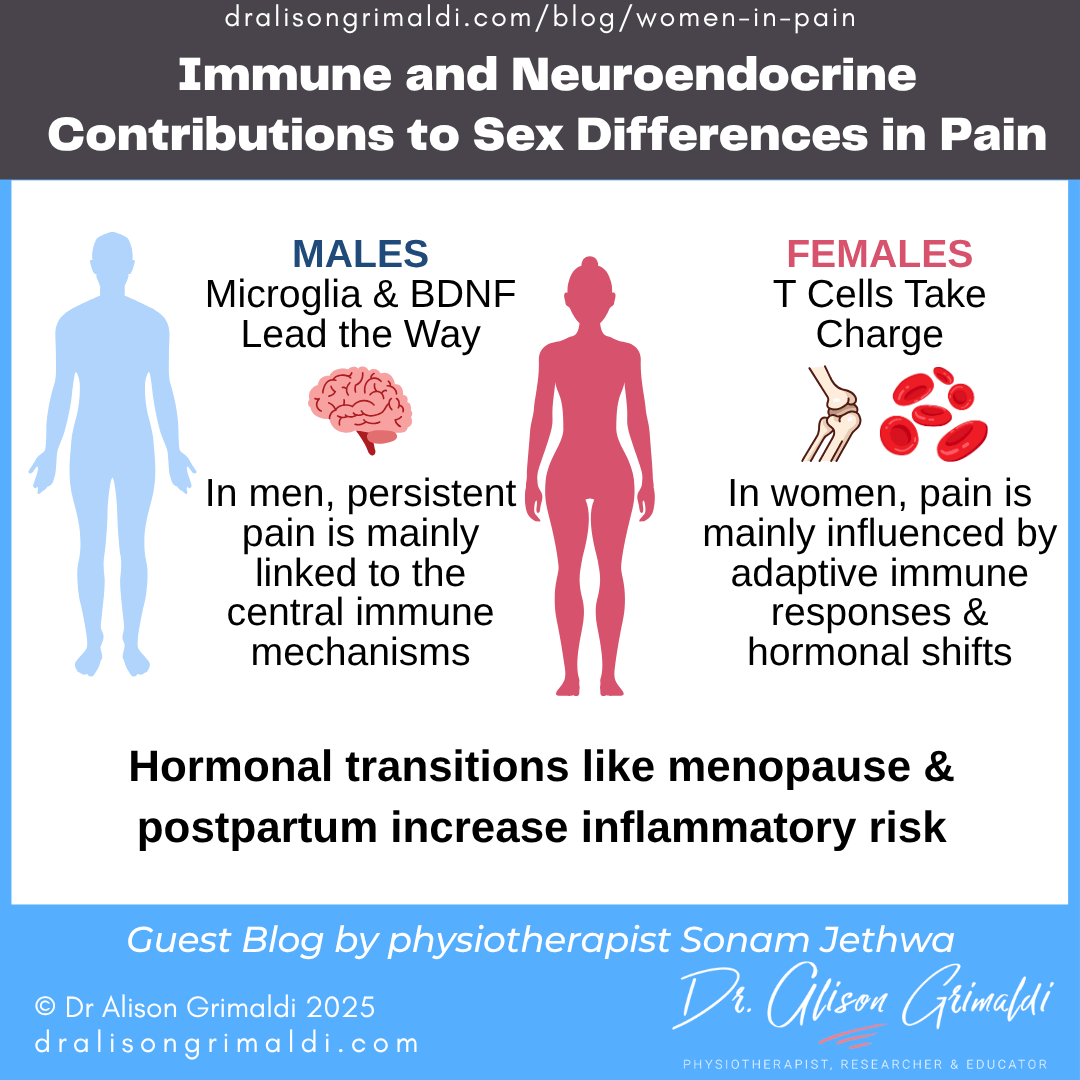

Immune and Neuroendocrine Contributions to Sex Differences in Pain

Emerging evidence suggests distinct immune mechanisms underpin persistent pain in males and females. In male patients, microglial activation and BDNF expression are central, whereas in females, adaptive immune responses involving infiltrating T cells predominate.19 These biological sex differences necessitate a nuanced understanding of inflammatory pain mechanisms. For example, women in low-oestrogen states (e.g., post-menopause) often demonstrate a proinflammatory cytokine profile, contributing to systemic and musculoskeletal inflammation.1

Additionally, hormonal withdrawal states (e.g., menopause, postpartum) are increasingly being recognised as risk periods for the emergence or exacerbation of musculoskeletal symptoms. Inflammatory arthropathies such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus also demonstrate higher prevalence and severity in women, with symptom onset often linked to reproductive transitions.5

Furthermore, immune-hormonal interactions may underpin sex-specific differences in autoimmune risk. Oestradiol influences immune cells such as T-lymphocytes and macrophages, shifting the immune balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory states depending on concentration.1 This may help explain the observed higher prevalence of autoimmune and inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions among women.

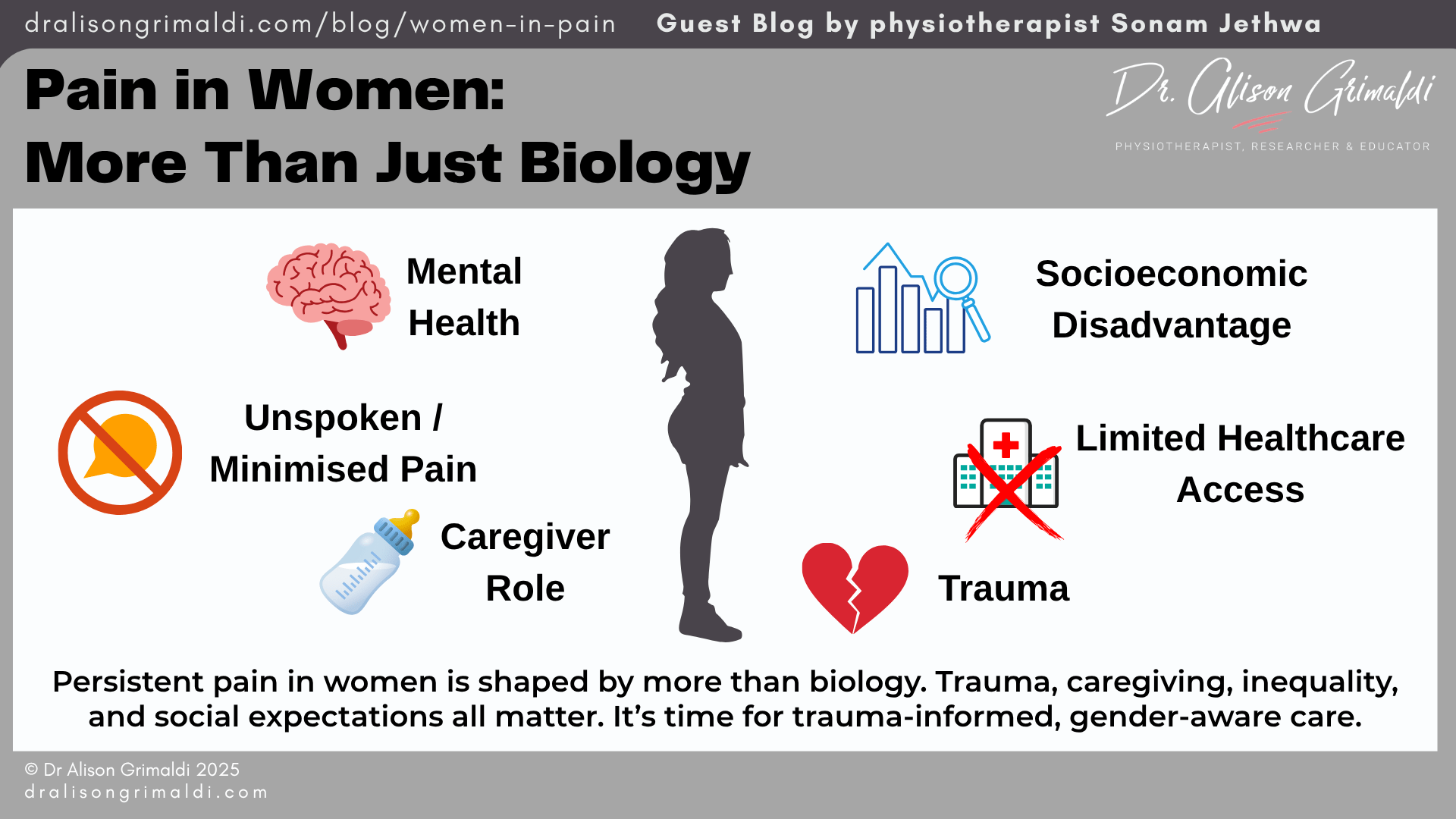

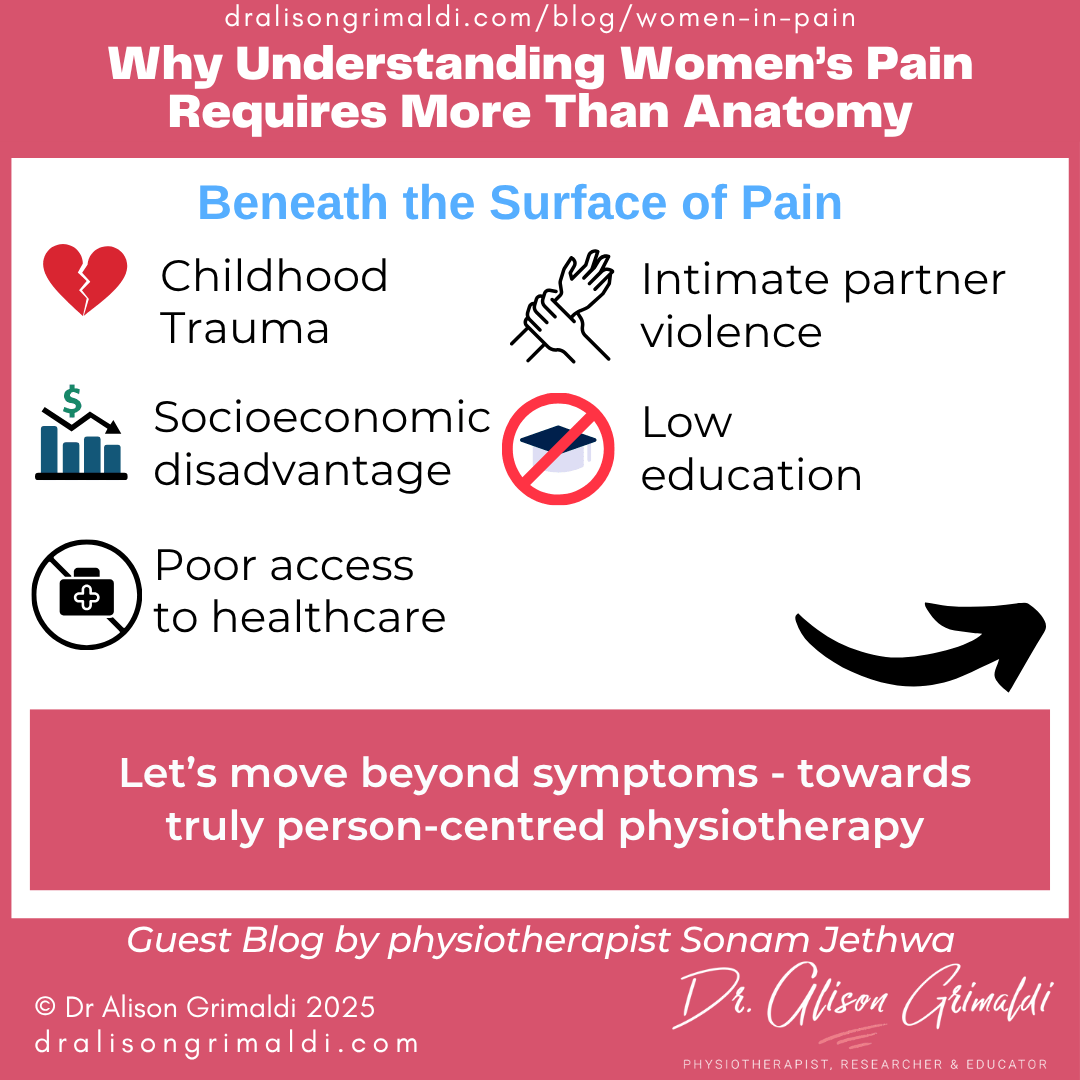

Psychosocial Determinants and Gender-Based Vulnerabilities

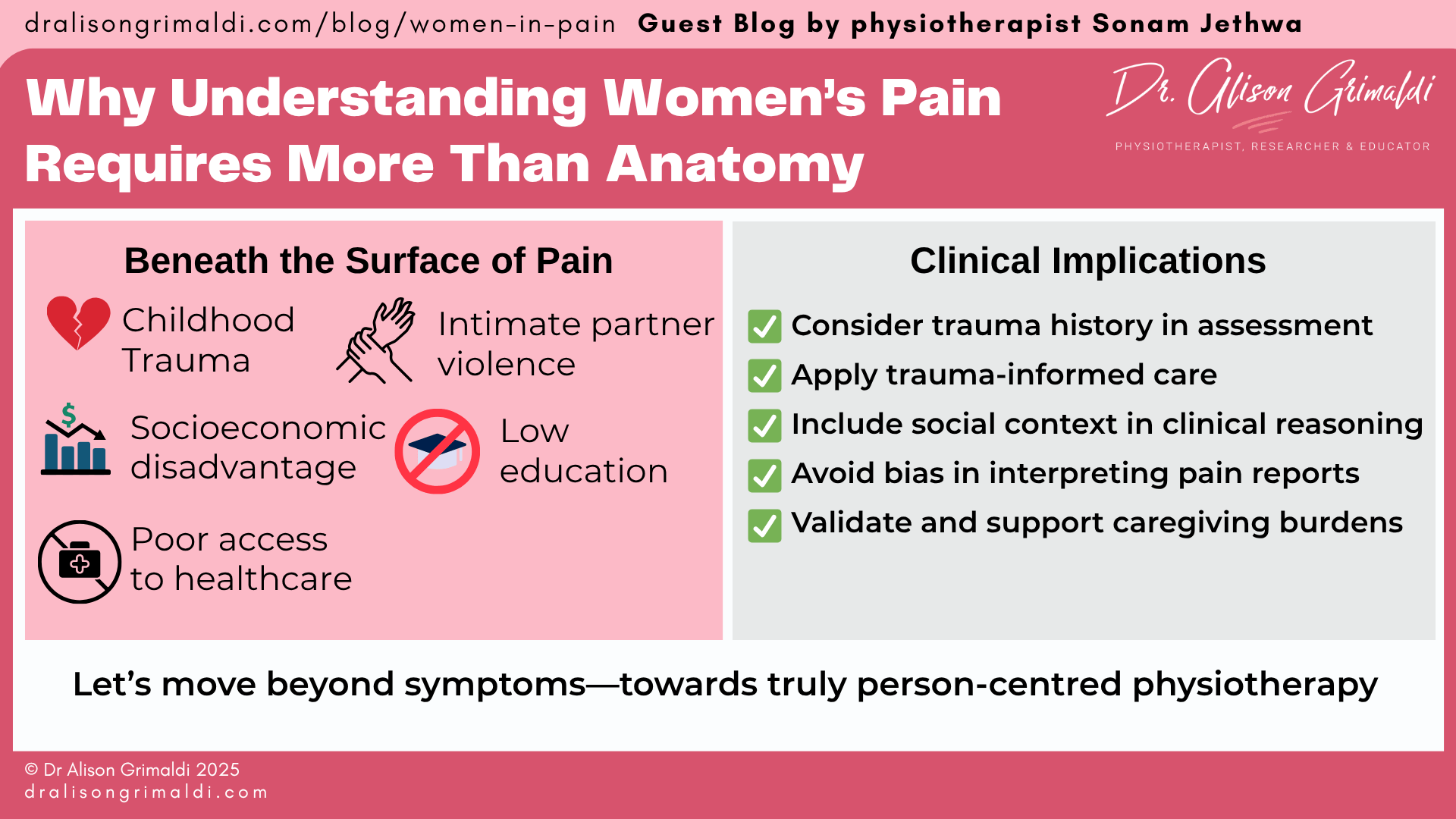

Pain in women is shaped not only by biology but also by lived experiences. A history of trauma, especially in childhood or in the context of intimate partner violence, significantly increases the risk of developing persistent pain states.20

Moreover, socioeconomic disadvantage, caregiving roles, low educational attainment, and poor access to healthcare have all been associated with pain persistence.6 Women with persistent pain are more likely to experience depression, anxiety, and social withdrawal, further compounding the biopsychosocial complexity.21

The burden of pain is not evenly distributed, and these disparities are rarely captured in traditional outcome measures or rehabilitation plans. This highlights a critical need for trauma-informed care and social determinants to be explicitly considered within clinical reasoning.

Additionally, societal expectations may influence how women report or interpret pain. Women are often socialised to endure discomfort and prioritise caregiving, which can delay help-seeking or minimise their perceived need for rest or recovery.22 Understanding these dynamics is essential for clinicians to provide validation and contextualised support.

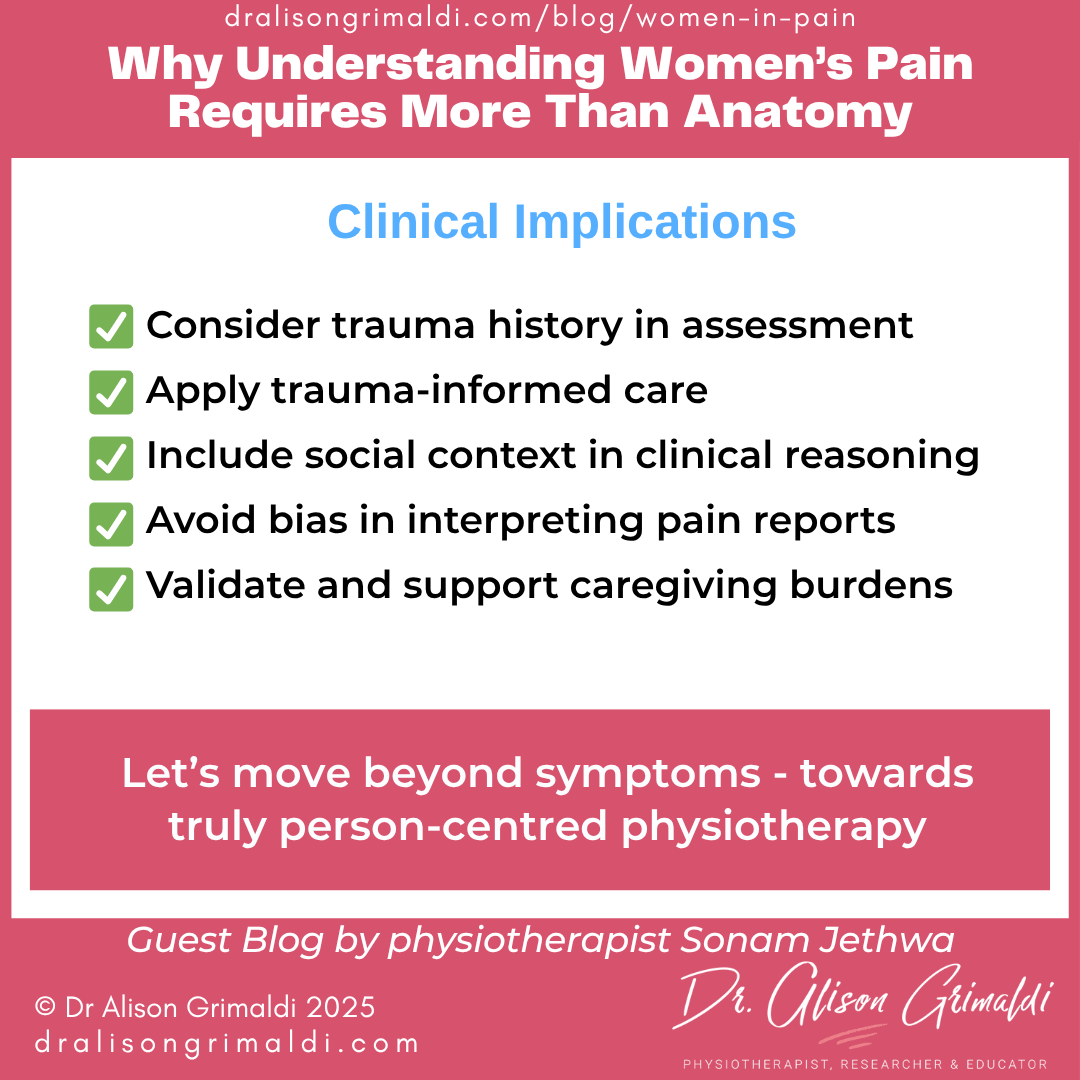

Clinical Implications for Physiotherapy Practice

To address these disparities, MSK clinicians must integrate female-specific considerations into assessment and management. This includes:

- Taking a detailed hormonal history (such as age at menarche, menstrual patterns, menopause – natural/ surgical, contraceptive use, endometriosis/ adenomyosis).

- Early menarche (typically between ages 9 and 11) has been associated with an increased risk of chronic pain conditions involving the neck, abdomen, upper limbs, and chronic widespread pain (CWP).23

- Screening for trauma and psychosocial risk factors.

- Identifying patients at risk using tools like the Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire (OREBRO-SF) and the Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI).

- Adapting exercise interventions to account for or adapt to hormonal phases, immune system profile and psychosocial situation.

- Advanced frameworks like the Pain and Movement Reasoning Model24 offer valuable structure, which can be enhanced with a female-centred lens to integrate sex-specific factors into clinical reasoning.

- Call for researchers to develop outcome measures that identify females at risk of persistent pain by incorporating female-specific variables such as hormonal status, trauma history, and psychosocial factors.

Furthermore, integrating exercise as a therapeutic tool must be done with caution in women with conditions like RED-S or autoimmune, where overtraining may exacerbate painful condition.25

Clinicians should also embrace person-centred care approaches, validating the patient’s lived experience, and offering shared decision-making.26 This involves explaining why certain symptoms may be hormonally modulated or psychosocially influenced without attributing pain solely to mood or stress.

Educational reform is also essential. Clinicians must be trained in sex- and gender-based medicine and taught to critically appraise literature for sex bias. The Sex and Gender Health Education Summit 2020 recommends that healthcare professionals develop competencies in sex-based pain management, critical appraisal, and advocacy.27

Conclusion: Towards Equitable Musculoskeletal Practice

Rethinking musculoskeletal pain in women is not about introducing new protocols. It is about refining clinical reasoning, expanding our lens, and acknowledging the systemic biases that shape our practice.

Pain is a multidimensional, lived experience. When we fail to consider the role of sex hormones, immune profiles, trauma history, and social context, we fail half the population. Bridging the gender pain gap requires intentionality, education, and the development of outcome measures that reflect women's realities.

As clinicians, educators, and researchers, we must lead the charge in transforming musculoskeletal care from a one-size-fits-all model to one that recognises and responds to the unique needs of women. Ultimately, integrating female-specific perspectives into musculoskeletal care is not a "niche interest"; it is essential for equitable, effective, and evidence-informed practice.

Have you heard about Hip Academy?

Transform the way you approach hip and buttock pain. Get the confidence to treat complex and challenging joint, tendon and nerve related pain.

With all Hip Courses included, enjoy all the extra inclusions, including; access to the entire eBook series, how-to video library, expanding PDF resource centre, live masterclasses, Q&A and Member Case Sharing sessions + a library of recordings!

Begin your Transformation!

Master Hip and Pelvic Conditions:

Gain expert knowledge and skills to assess and treat challenging hip and pelvic conditions with evidence-based methods.

Professional Growth:

Transform into a highly skilled hip specialist through structured learning and access to cutting-edge research and techniques.

Confidence in Practice:

Enhance your clinical confidence when dealing with complex hip issues, knowing you have the latest evidence and strategies at your fingertips.

Global Community Engagement:

Connect with a worldwide network of health professionals, exchanging ideas and learning from peers and experts in the field.

Continuous Learning:

Keep up with the latest advancements and research in hip physiotherapy, ensuring you stay at the forefront of your profession.

This blog was written by Sonam Jethwa

Sonam is an Australian physiotherapist with extensive knowledge in the assessment and management of acute, persistent, and complex musculoskeletal conditions. She has Australian Physiotherapy Association Titles for both Musculoskeletal and Sports & Exercise Physiotherapy. Having completed her dual Master’s degree at the University of South Australia in 2012, she is now in her final year as a Registrar with the Australian College of Physiotherapists, pursuing Specialisation in Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy. Currently, based in Melbourne, Victoria, Sonam works in private practice, combining her advanced clinical skills with a strong commitment to evidence-based person-centred care.

Sonam is also a long term Hip Academy member, having presented a masterclass on this topic for members (recording available for members), and a great case study on a non-MSK presentation of hip pain that we should all be on the lookout for. If you'd like to benefit from the knowledge of the Hip Academy Brains Trust, get started today with a Hip Academy membership.

Check Out Some More Relevant Blogs

References

- M. Gulati, E. Dursun, K. Vincent, and F. E. Watt, “The influence of sex hormones on musculoskeletal pain and osteoarthritis,” Lancet Rheumatol, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. e225–e238, Apr. 2023, doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00060-7/ASSET/3D182031-16EE-421E-84CB-BD49048CCA2C/MAIN.ASSETS/GR4.SML.

- “Chronic musculoskeletal conditions , Summary - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.” Accessed: Jan. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/musculoskeletal-conditions/contents/summary#impact

- “Pain In Women - International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).” Accessed: Jan. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/fact-sheets/pain-in-women/

- M. Gulati, E. Dursun, K. Vincent, and F. E. Watt, “The influence of sex hormones on musculoskeletal pain and osteoarthritis,” Lancet Rheumatol, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. e225–e238, Apr. 2023, doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00060-7/ASSET/3D182031-16EE-421E-84CB-BD49048CCA2C/MAIN.ASSETS/GR4.SML.

- M. K. Desai and R. D. Brinton, “Autoimmune Disease in Women: Endocrine Transition and Risk Across the Lifespan,” Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), vol. 10, no. APR, p. 265, 2019, doi: 10.3389/FENDO.2019.00265.

- W. Maixner, R. B. Fillingim, D. A. Williams, S. B. Smith, and G. D. Slade, “Overlapping Chronic Pain Conditions: Implications for Diagnosis and Classification,” J Pain, vol. 17, no. 9, pp. T93–T107, Sep. 2016, doi: 10.1016/J.JPAIN.2016.06.002.

- “Biological Mechanisms Underlying Sex Differences in Pain - International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).” Accessed: Apr. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/fact-sheets/biological-mechanisms-underlying-sex-differences-in-pain/

- “THE GENDER PAIN GAP REVEALED-AND WOMEN AREN’T SURPRISED,” 2024.

- “The Gender Pain Gap Revealed – And Women Aren‘t Surprised | Premier.” Accessed: Nov. 06, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.premier.vic.gov.au/gender-pain-gap-revealed-and-women-arent-surprised

- K. Yoshikawa, B. Brady, M. A. Perry, and H. Devan, “Sociocultural factors influencing physiotherapy management in culturally and linguistically diverse people with persistent pain: a scoping review,” Physiotherapy, vol. 107, pp. 292–305, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.1016/J.PHYSIO.2019.08.002.

- “Sex/Gender Biases in Pain Research and Clinical Practice - International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).” Accessed: Jan. 25, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/fact-sheets/sex-gender-biases-in-pain-research-and-clinical-practice/

- “Sex/Gender Biases in Pain Research and Clinical Practice - International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).” Accessed: Nov. 08, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/fact-sheets/sex-gender-biases-in-pain-research-and-clinical-practice/

- “RACGP - Gender bias is still putting women’s health at risk.” Accessed: Jan. 26, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/gender-bias-in-medicine-and-medical-research-is-st

- eClinicalMedicine, “Gendered pain: a call for recognition and health equity,” EClinicalMedicine, vol. 69, Mar. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102558.

- “Gender Differences in Chronic Pain Conditions - International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).” Accessed: Jan. 22, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/fact-sheets/gender-differences-in-chronic-pain-conditions/

- H. Razmjou, S. Lincoln, I. Macritchie, R. R. Richards, D. Medeiros, and A. Elmaraghy, “Sex and gender disparity in pathology, disability, referral pattern, and wait time for surgery in workers with shoulder injury,” BMC Musculoskelet Disord, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Sep. 2016, doi: 10.1186/S12891-016-1257-7/TABLES/4.

- D. E. Hoffmann and A. J. Tarzian, “The girl who cried pain: a bias against women in the treatment of pain,” J Law Med Ethics, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 13–27, 2001, doi: 10.1111/J.1748-720X.2001.TB00037.X.

- S. A. Nasser and E. A. Afify, “Sex differences in pain and opioid mediated antinociception: Modulatory role of gonadal hormones,” Life Sci, vol. 237, Nov. 2019, doi: 10.1016/J.LFS.2019.116926.

- “Biological Mechanisms Underlying Sex Differences in Pain - International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).” Accessed: Nov. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/fact-sheets/biological-mechanisms-underlying-sex-differences-in-pain/

- L. Frenkel, L. Swartz, and J. Bantjes, “Chronic traumatic stress and chronic pain in the majority world: notes towards an integrative approach,” Crit Public Health, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 12–21, Jan. 2018, doi: 10.1080/09581596.2017.1308467.

- M. Racine, Y. Tousignant-Laflamme, L. A. Kloda, D. Dion, G. Dupuis, and M. Choinire, “A systematic literature review of 10 years of research on sex/gender and pain perception - Part 2: Do biopsychosocial factors alter pain sensitivity differently in women and men?,” Pain, vol. 153, no. 3, pp. 619–635, 2012, doi: 10.1016/J.PAIN.2011.11.026.

- R. Pedulla et al., “Associations of Gender Role and Pain in Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review,” J Pain, vol. 25, no. 12, p. 104644, Dec. 2024, doi: 10.1016/J.JPAIN.2024.104644.

- C. I. Lund et al., “The association between age at menarche and chronic pain outcomes in women: the Tromsø Study, 2007 to 2016,” Pain, vol. 163, no. 9, p. 1790, Sep. 2022, doi: 10.1097/J.PAIN.0000000000002579.

- L. E. Jones and D. F. P. O’Shaughnessy, “The Pain and Movement Reasoning Model: Introduction to a simple tool for integrated pain assessment,” Man Ther, no. 3, pp. 270–276, Jun. 2014, Accessed: Sep. 15, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://find.library.unisa.edu.au

- B. Luo et al., “The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise on autoimmune diseases: A 20-year systematic review,” J Sport Health Sci, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 353–367, May 2024, doi: 10.1016/J.JSHS.2024.02.002.

- N. Hutting, J. P. Caneiro, O. M. Ong’wen, M. Miciak, and L. Roberts, “Patient-centered care in musculoskeletal practice: Key elements to support clinicians to focus on the person,” Musculoskelet Sci Pract, vol. 57, p. 102434, Feb. 2022, doi: 10.1016/J.MSKSP.2021.102434.

- J. M. Kling et al., “Sex and Gender Health Educational Tenets: A Report from the 2020 Sex and Gender Health Education Summit,” J Womens Health, vol. 31, no. 7, p. 905, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1089/JWH.2022.0222.