How physiotherapists treat gluteal tendinopathy

Can't make the workshop? Do the Online Course

More than 97% of 743 physiotherapists surveyed across two studies in the United Kingdom (UK), Ireland, Australia and New Zealand (NZ)1,2

- are somewhat, or very confident in the management of GTPS,

- provide education on load management and self-management strategies,

- prescribe an exercise programme, including strengthening exercises .

On face value, it appears that physiotherapists are confidently managing gluteal tendinopathy/GTPS in an evidence-based fashion, with knowledge translation complete. So, can researchers and educators move on? Perhaps not quite yet. On delving deeper into the details of these survey results and noting varying outcomes in clinical trials, it is clear that we still have much ground to cover. In this age of social media, general principles such as ‘Apply load management and strengthening for GTPS’ are easily translated but a comprehensive understanding of the condition, proposed aetiological mechanisms, and the evidence base for treatment strategies are less readily translated via this medium.

If you have gluteal tendinopathy or trochanteric bursitis yourself (pain over the side of the hip), you can find my self-help course here: Recovering from Gluteal Tendinopathy, Trochanteric Bursitis and Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome

Load management for gluteal tendinopathy /GTPS

Load management advice for gluteal tendinopathy/GTPS is provided (often or always) by almost 100% of physiotherapists surveyed in the UK, Ireland, Australia and NZ1,2 and yet, of those surveyed:

- only 38.6% of UK physiotherapists (often or always) discuss postural strategies,

- 39% sometimes, often or always prescribe stretching for the hip abductors, and

- 32% of Irish, Australian and NZ physiotherapists prescribe stretching for the Iliotibial band.

Inclusion of 'load management advice' is now widely accepted as a fundamental element of a management program for gluteal tendinopathy/GTPS and for tendinopathy in general 3,4,5. But what exactly does that mean and how is it being implemented in clinical practice?

While addressing 'posture' has become a contentious topic in contemporary practice (I have discussed this is a previous blog), sustained joint positions account for a substantial proportion of time exposure to compressive loads at tendon entheses. For gluteal tendinopathy, hip adduction in everyday life; sitting with knees crossed, standing in ‘hip hanging’/adducted postures and side sleeping adds to the cumulative compressive load at the greater trochanter. Yes, compression is normal, but high levels of cumulative exposure together with pathological and psychological factors, contribute to the risk profile for the development and persistence of pain and disability associated with tendinopathy. For the same reason, stretches for insertional tendinopathies are no longer advised, owing to their compressive and therefore potentially provocative nature5.

If more than 60% of physiotherapists are not regularly addressing postural strategies and 30-40% continue to prescribe stretching of the ITB or hip abductors, what exactly is being provided as ‘load management’ advice? Non-specific advice on reducing activity levels to control symptoms and then gradually reloading as pain allows, is important in the overall management of tendinopathy. Where the presentation is a reactive tendon response to a short-term spike in activity, such advice may be sufficient. However, if the situation of tendon overload is underpinned by inherent postural and movement patterns, simply unloading and reloading is unlikely to be an adequate longer-term solution.

‘Load management’ for gluteal tendinopathy encompasses more than simply reducing and then rebuilding overall volume or intensity of activity. Identifying and reducing individual exposure to excessive, repetitive, loaded and sustained hip adduction in activities of daily living and sport may be key for many patients, particularly in the longer term.

If you have gluteal tendinopathy or trochanteric bursitis yourself (pain over the side of the hip), you can find my self-help course here: Recovering from Gluteal Tendinopathy, Trochanteric Bursitis and Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome

Functional movement training for gluteal tendinopathy

These survey studies also provide some interesting insights into the types of exercise that physiotherapists prescribe to patients with gluteal tendinopathy:

- 98.4% of physiotherapists surveyed in the UK always or often prescribe strengthening, and

- 99.7% report using functional exercises as a common mode of strengthening,

AND YET,

- only 51.4% always or often provide gait training and

- only 62% always or often provide functional movement training2.

The substantially lower use of neuromotor compared with strengthening exercise was more notable in the UK survey. In Australia, NZ and Ireland, about 80% of surveyed physiotherapists report always or often using functional movement and gait training1.

Good evidence of hip abductor muscle strength deficits in those with gluteal tendinopathy exists, supporting the prescription of strengthening exercise6,7 . There is also evidence that kinetic and kinematic alterations in gait and other single limb loading tasks exist in those with gluteal tendinopathy8. An important component of the successful LEAP randomised clinical trial (RCT) protocol was neuromotor style training that aimed to address kinematic patterns potentially contributing to provocative gluteal tendon loading3.

The disparity between provision of 'functional strengthening' (99.7%) and 'functional movement training' (62%) in the UK may reflect a clinical bias, perhaps influenced by social media. Is it possible that some clinicians perceive that functional 'strengthening' is more socially acceptable than 'movement training.' As with posture, in recent years there has been a shift away from neuromotor training in some regions and social platforms.

There has been social suggestion that trying to change the way someone moves is

1. not evidence-based and

2. fear inducing.

The hypothesis appears to be that by simply adding load slowly and reducing fear with education, that the body can adapt to any movement pattern, regardless of biology or pathology. In the management of gluteal tendinopathy, there is no evidence that training a patient to reduce excessive hip adduction during a functional task such as a squat or step up prior to adding load, is more effective than reassuring the patient, simply leaving an excessively adducted pattern as it is and slowly adding load. As there is no direct evidence to support either assertion, we can only rely on basic science evidence for clinical plausibility. Such evidence would not support loading in excessive adduction, due to persistence of provocative compressive loads applied across the gluteal tendons, which is probably one of the reasons why the study has not been done - selling this to an ethics board may be challenging!

Furthermore, the psychological impact of training movement alterations will be strongly mediated by the language used. As long as appropriate language is selected, movement training that reduces provocative tendon loading is not fear inducing. On the contrary, practising everyday functional tasks with movement guidance (as required) from a health professional is generally empowering. Participants of the LEAP trial who performed neuromotor and strength training under the supervision of a physiotherapist, reported significantly higher levels of pain self-efficacy after the 8-week intervention than other groups3. Although the exact mediator of effect is unknown, the superior pain self-efficacy scores reflect the improved confidence imparted by the education and exercise program.

The relatively lower numbers of surveyed physiotherapists providing gait training in the UK is also of note. Allison and colleagues demonstrated that individuals with gluteal tendinopathy walked with external hip adduction moments 9%-33% higher through stance than painfree controls, imposing much higher loads on the hip abductor tendons8. If our patients are taking somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000 steps per day, there is a great opportunity here for reducing the daily load imposed on the gluteal tendons through alterations in gait pattern. Why then are only 50% of UK physiotherapists regularly providing gait training for patients with gluteal tendinopathy? Is it lack of awareness, clinical bias (perhaps socially influenced), lack of time and therefore prioritisation of strengthening exercise or perhaps a lack of confidence in gait analysis and training? Clinicians who do not address gait and the way those with gluteal tendinopathy dynamically load their tendons, may well be withholding an important component of a successful rehabilitation program.

Altering gluteal tendon loads during functional movement and gait training should not be undervalued. Simple advice and cues to address overt features can return rapid and meaningful positive change. Such changes have the potential to continue providing benefit well after a patient's compliance with a strengthening program wanes.

Which exercises are best for gluteal tendinopathy?

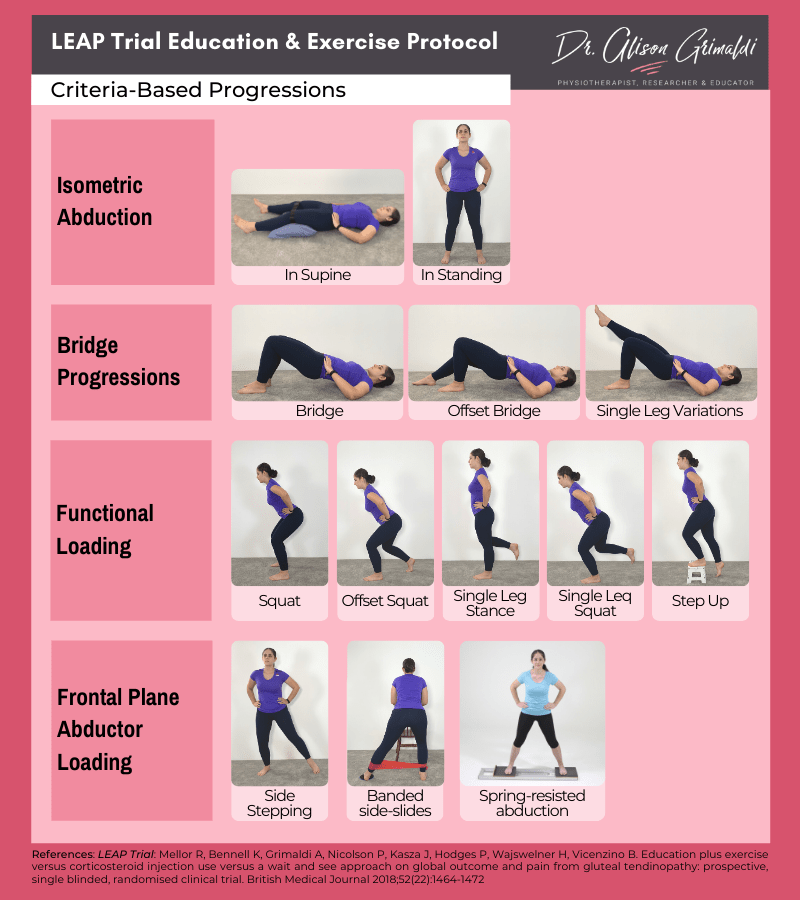

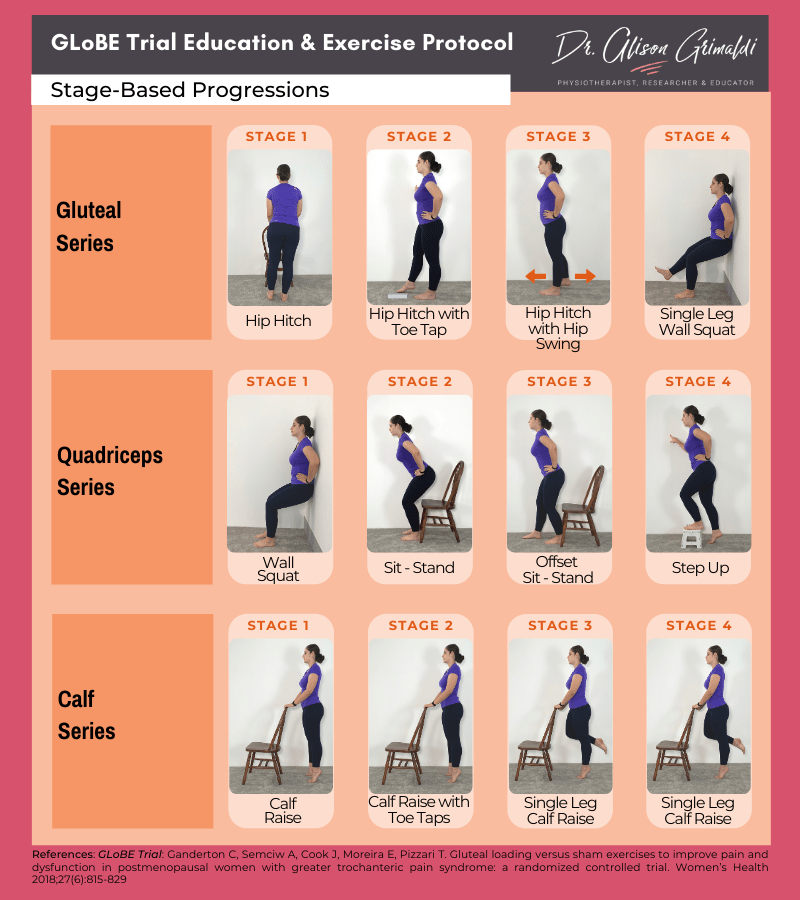

Apart from functional exercises, which can impart both strength and neuromotor benefits, what other exercises are employed to target the hip abductors? Does it matter what and how abductor strengthening is prescribed; isometric, isotonic, weightbearing, non-weightbearing? Most physiotherapists surveyed appear to use a variety of exercise modes1,2. There is inadequate evidence at this point to clearly support selection of individual exercises. However, examination of the similarities and differences between programs utilised by RCTs so far, may provide direction for future research and points of reflection for the clinician. The two RCT’s that have compared education and exercise interventions for gluteal tendinopathy; the LEAP trial3 and the GLoBE trial4, both used a variety of exercises that were progressed over the duration of the intervention (see figures below).

If you have gluteal tendinopathy or trochanteric bursitis yourself (pain over the side of the hip), you can find my self-help course here: Recovering from Gluteal Tendinopathy, Trochanteric Bursitis and Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome

Although disparate outcome measures can make it difficult to compare outcomes across studies, both the LEAP and GLoBE trials used the VISA-G patient rated outcome scale, which measures pain and disability in those with gluteal tendinopathy and GTPS. There is 3 month data available for both studies, by which time participants following the LEAP protocol had improved by an average of 31.7% from the baseline score (60.2/100) and those following the GLoBE protocol had improved by an average 18.7% from the baseline score (61.6/100).

The GLoBE trial compared the GLoBE protocol with a sham exercise program and found that both groups improved, with no between-group differences in either the short (3 months) or long (12 months) term4. The authors’ primary conclusion was that ‘Lack of treatment effect was found with the addition of an exercise programme to comprehensive education on GTPS management’.

So this could either mean that:

1. the education and not the exercise was the active ingredient for change, or

2. the exercise program had inadequate effect.

Both the LEAP and GLoBE protocols included a comprehensive education program, so the difference in outcomes may indicate that it's worth taking a closer look at the exercise interventions.

Both protocols provided weightbearing exercises with no provocative stretching. However, there were a number of differences between the protocols (see figure above), any of which may have influenced outcomes. Did the lack of heavy slow loading, frontal plane abductor loading, gait and functional movement training, physiotherapist supervision or lower levels of participant compliance play a role in poorer VISA-G outcomes from the GLoBE protocol?

There is currently no answer to this question, but if your programs are not returning the outcomes expected or desired, I would encourage you to re-evaluate the key features of your program and try altering some of the specific aspects discussed here and monitor the effects.

If you have gluteal tendinopathy or trochanteric bursitis yourself (pain over the side of the hip), you can find my self-help course here: Recovering from Gluteal Tendinopathy, Trochanteric Bursitis and Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome

Learn about gluteal tendinopathy Ax & Mx and much more here

All diagnostic tests for gluteal tendinopathy & LEAP exercise videos available within my video library

Another great Lateral Hip Pain blog

Lateral Hip Pain: Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment