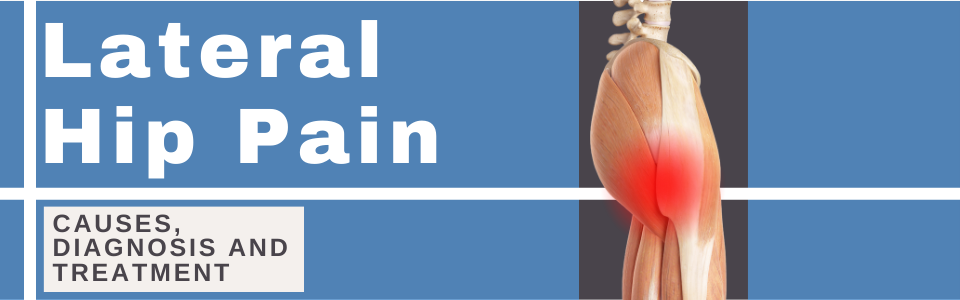

Lateral Hip Pain: Causes, diagnosis and treatment

Lateral hip pain is a common presentation, particularly in post-menopausal women. Soft tissue causes of lateral hip pain alone impacting almost one in every 4 women between the ages of 50 and 70 years,1 with soft tissue and joint causes of lateral hip pain incurring substantial adverse impacts of quality-of-life. This blog aims to provide you with an overview of causes, diagnosis and treatment of lateral hip pain. I’ll bring together some key information on this topic and signpost where you can find more detail.

In this blog we’ll be covering:

Discover our Lateral Hip & Buttock Pain Course

If you enjoyed this blog, you might like to take the online course on Lateral Hip & Buttock Pain - 6 hours of guided online video content. Examine various joint-related, soft tissue-related and nerve-related conditions associated with lateral hip and buttock pain, their mechanisms, associated impairments, clinical diagnostic tests and management approaches. To learn more, take the lateral hip and buttock pain online course, or join me in an online or practical lateral hip and buttock pain workshop.

Causes of lateral hip pain

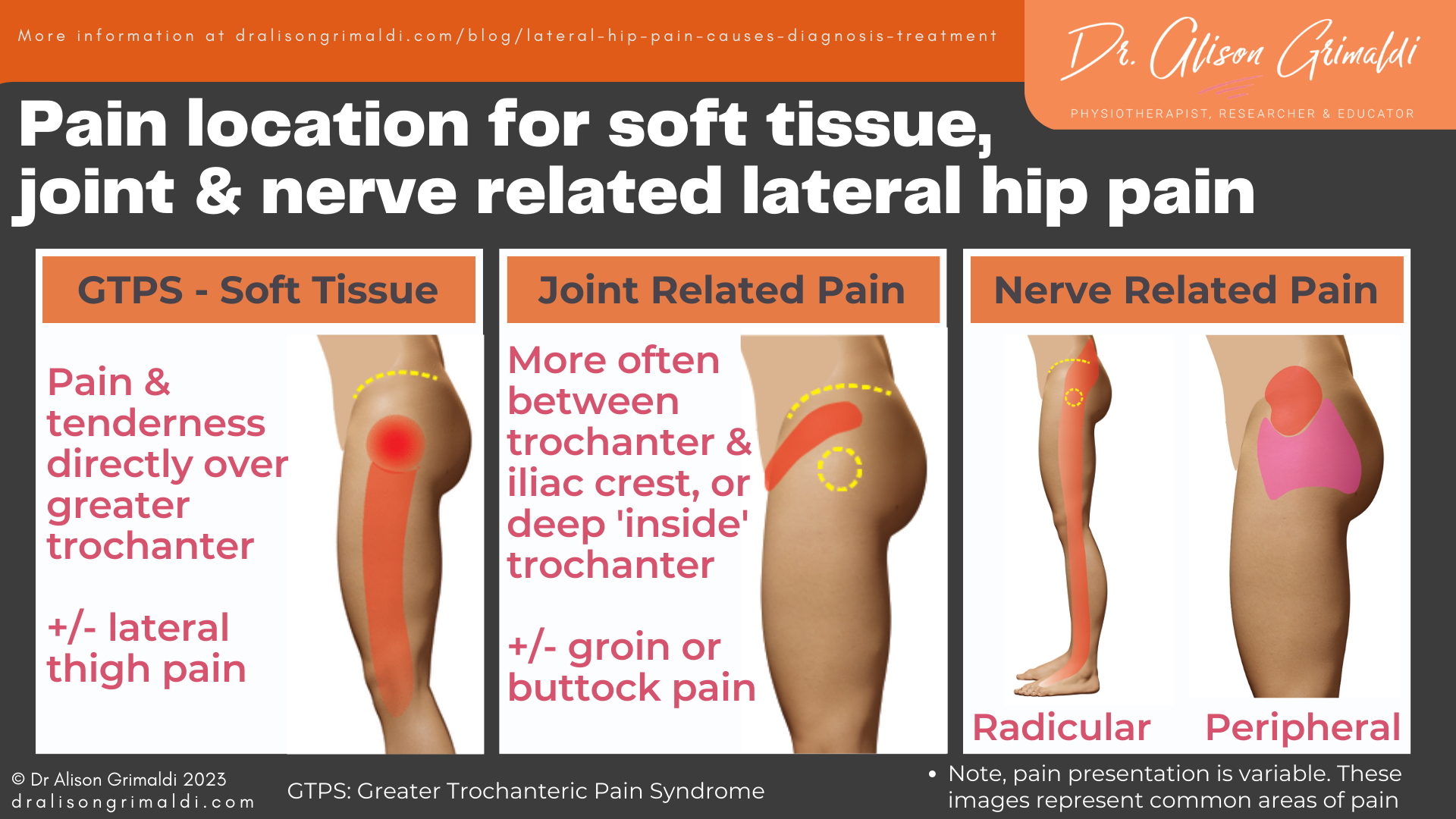

Lateral hip pain is most commonly associated with local soft tissue pathology, but may also be related to the underlying hip joint, local nerves or referring nerve roots, bony structures or more remote sources. Area of pain provides an important clue, as well as the nature and behaviour of pain and patient history and health.

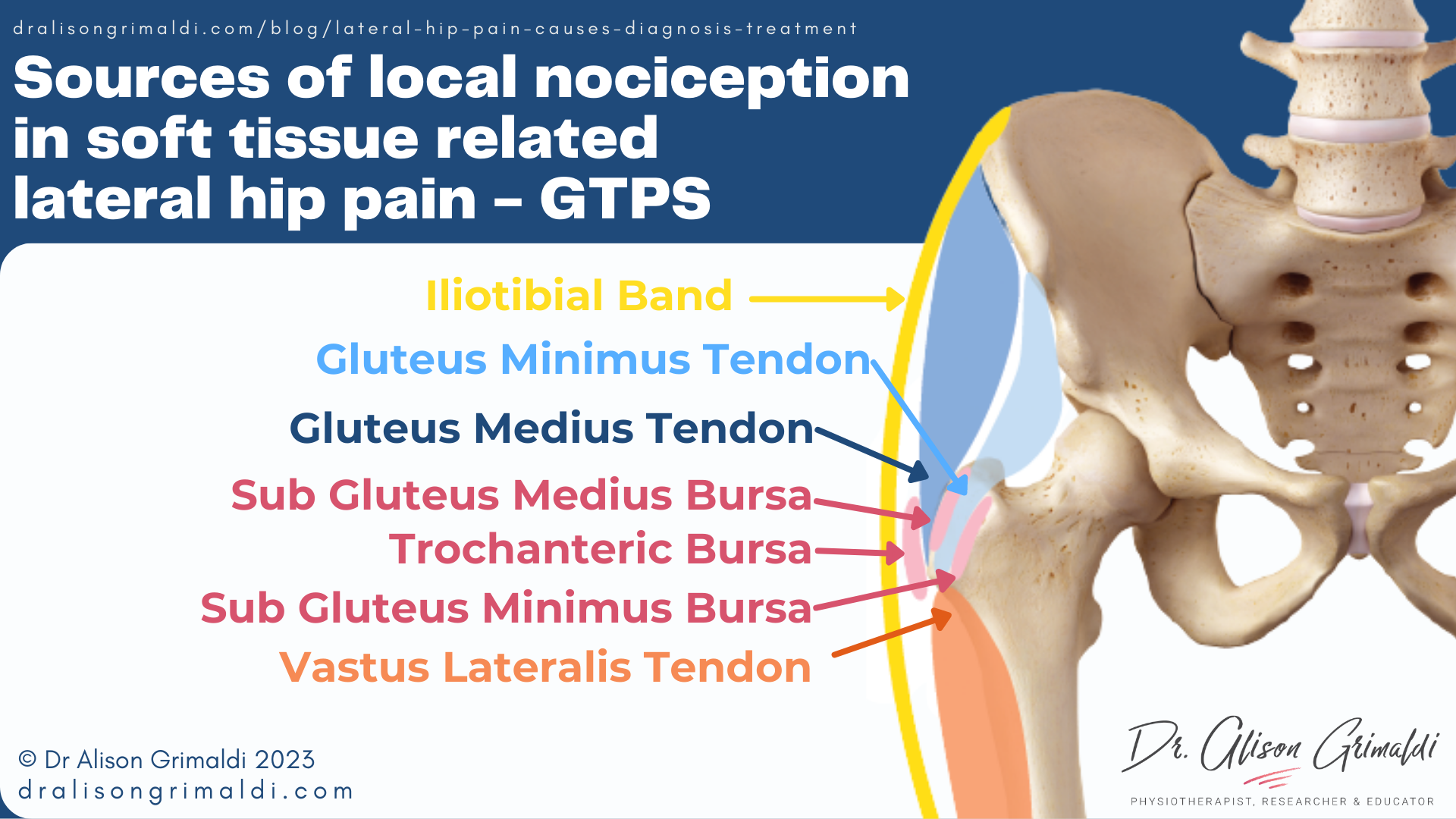

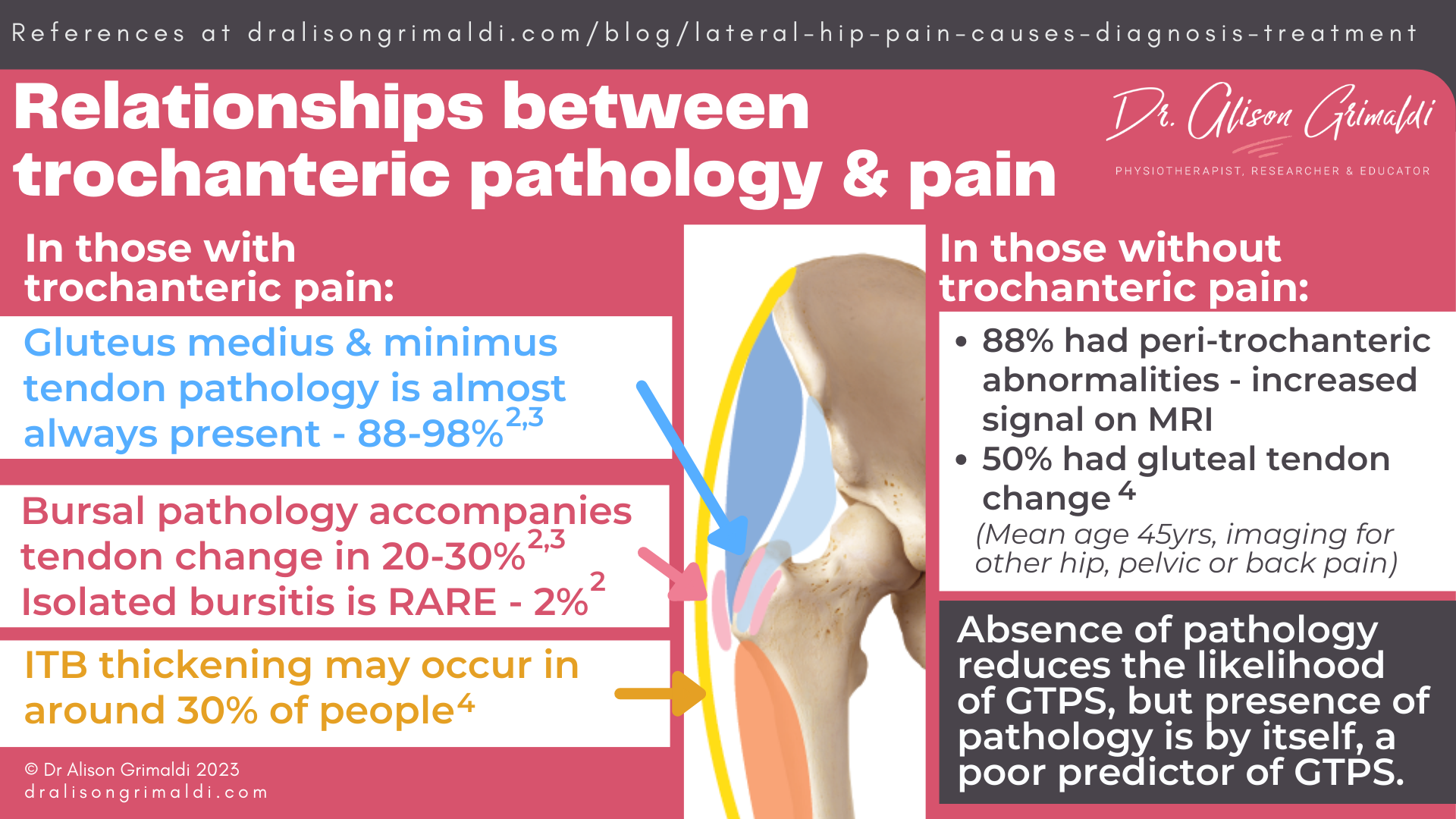

A recent imaging study reported that only 2% of participants had isolated trochanteric bursitis, while 69% had abductor tendon pathology with no bursitis, and the remaining 29% had mixed pathology – abductor tendon pathology with bursal change in one of the bursae of the greater trochanter.2

Thickening of the iliotibial band has also been identified in almost 30% of people with trochanteric pain.3 Bony spurring may occur from the greater trochanter, either up into the gluteal tendons and/or down into the proximal vastus lateralis tendon. The vastus lateralis tendon is generally not mentioned in clinical or research reports but does have an intimate relationship with the gluteal tendons at the inferior aspect of the greater trochanter.

Lateral hip pain of soft tissue origin is generally now referred to as gluteal tendinopathy, to reflect the primary pathology and incite an active approach to management similar to other tendinopathies. The other most common diagnosis is Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome (GTPS) which is an umbrella term that covers pain related to any trochanteric soft tissue pathology.

Prevalence and relevance of soft tissue pathology at the greater trochanter

As with other pathologies all around the bony, there is a mismatch between pathology and symptoms. Simply having soft tissue pathology at the greater trochanter does not mean it will necessarily be painful.

One MRI study reported that while patients with GTPS always had peritrochanteric T2 abnormalities, 88% of hips of those without trochanteric pain also had peritrochanteric abnormalities – high signal intensity.4 This indicates that while absence of peritrochanteric T2 abnormalities on MRI reduces the likelihood of GTPS, presence of peritrochanteric abnormalities is, by itself, a poor predictor of GTPS.

This is why the source of lateral hip pain (or any pain in fact) should never be determined through imaging alone. Correlation with clinical symptoms and signs is imperative.

Nerve related lateral hip pain

Nerve related lateral hip pain may be due to peripheral entrapment neuropathy or traumatic injury or radicular pain from the lumbar spine. Nerve related pain is most easily recognized when the description fits with typical neuralgic symptoms - sharp, stabbing or shooting pains, burning, tingling, itching, or numbness.

Peripheral nerve entrapment or injury at the lateral hip

The nerves that supply the cutaneous sensation for the lateral hip region include the lateral cutaneous branches of the subcostal and iliohypogastric nerves.7 These nerves exit the spine, pass between or through the paraspinal muscles, before piercing the abdominal wall and running over the iliac crest to serve the skin of the lateral hip.

The area where these nerves cross the iliac crest can be a region of potential injury or entrapment, particularly for the iliohypogastric nerve, that runs through a confined tunnel as it passes the iliac crest.

Tight clothing, belts or direct trauma e.g., from a lateral impact may cause injury. The other most common cause is iatrogenic – harvesting a bone graft from the iliac crest, large open surgeries to the abdominal wall or anterior approach lumbar surgeries.

Radicular lateral hip pain

Radicular pain arises from nerve root impingement or irritation. Radicular lateral hip pain most commonly arises from the L3 – S2 levels but this can vary significantly, with up to 2/3’s of people with entrapment neuropathy experiencing symptoms that do not correlate with defined territorial distributions.8

As opposed to gluteal tendinopathy, radicular pain in the lateral hip region is not localized to the trochanter, more commonly emanating from the buttock or lumbar region and transiting the lateral hip towards the thigh. Furthermore, aggravating factors are more likely to be related to positions or actions that load the lumbar spine - prolonged sitting, standing, bending, lifting.

Possible contributing factors and impairments associated with gluteal tendinopathy

Joint position and bony morphology

Compression, and particularly the combination of compression and tensile loads are considered to be important pathomechanical factors for the development of insertional tendinopathies like gluteal tendinopathy.

Compression of the tendons and associated bursae beneath the ITB occurs at the greater trochanter in positions of hip adduction, with a nine-fold increase in compressive loading even from neutral to 10° of hip adduction.11 Sustained positioning or movement in excessive hip adduction is likely one of the contributing factors for the development of soft-tissue related trochanteric pain.

Trochanteric compressive loads are also influenced by bony morphology, with higher compressive loads linked with lower femoral neck-shaft angles (coxa vara). Lower neck-shaft angles and greater trochanteric offset relative to width of the pelvis have been reported in those with greater trochanteric pain and lateral snapping hip.

In clinic, these are patients who appear to have quite prominent greater trochanters laterally, relative to their pelvic width. This prominence may result in the ITB wrapping more firmly around the greater trochanter in positions of hip adduction. Mind you, this is not always the case – consider this bony morphology a single risk factor.

Muscle deficits in those with gluteal tendinopathy

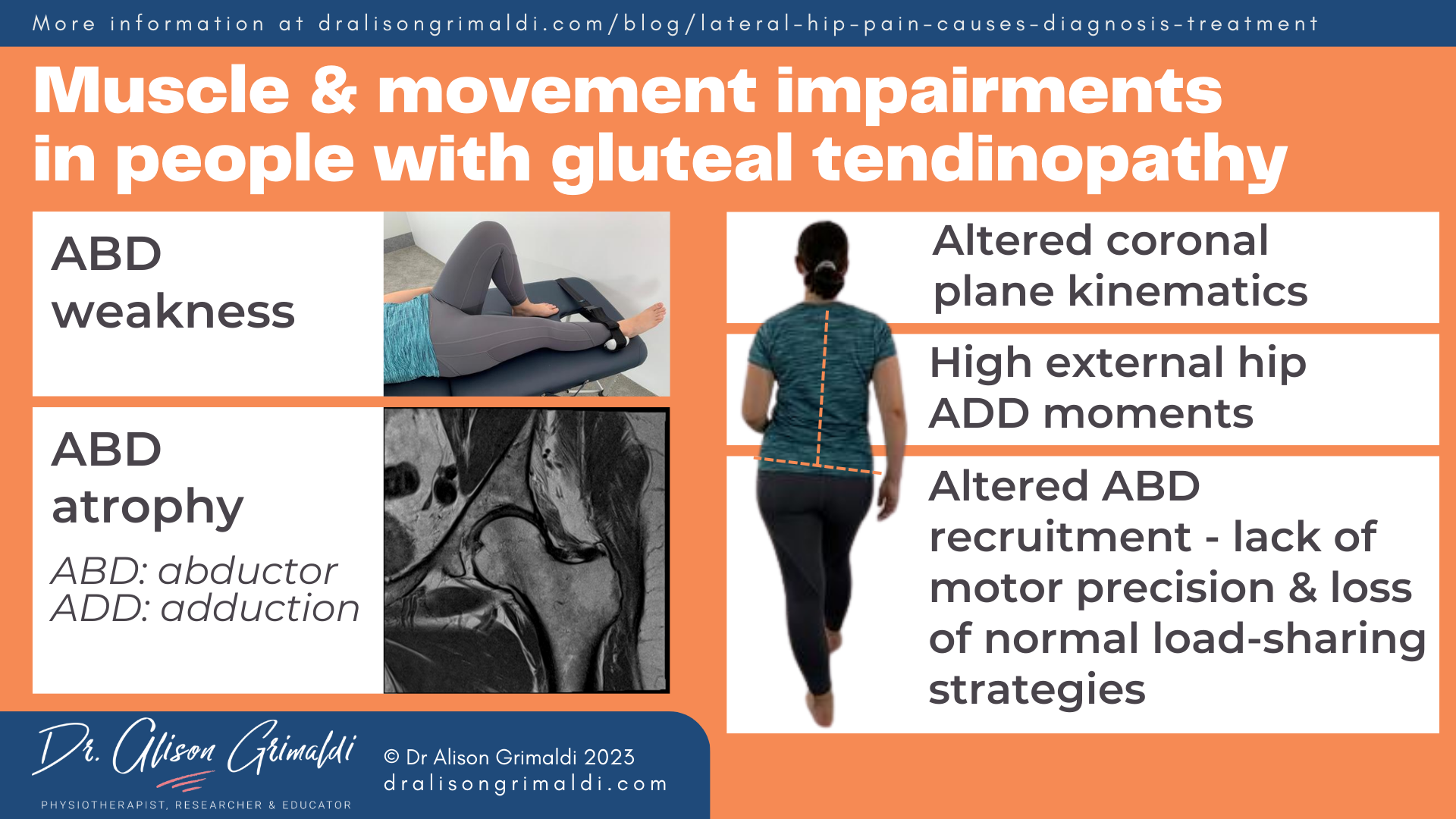

Hip abductor muscle weakness in gluteal tendinopathy and GTPS

Those with gluteal tendinopathy or GTPS have been shown to be weaker in the hip abductors, with strength deficits bilaterally even in unilateral presentations of the condition – 32% weaker on the painful side and 23% weaker on the other side, than a painfree control group.12

Hip abductor muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration in gluteal tendinopathy and GTPS

Hip abductor muscle atrophy has also been shown to accompany weakness. Smaller volumes of Gluteus maximus, medius and minimus muscles are smaller in volume, and greater fatty infiltration exists in gluteus maximus and minimus muscles in those with GTPS.13 In contrast, tensor fascia lata (TFL) muscle bulk and quality were not different between groups, indicating a relative shift in balance within the abductor muscle complex in those with greater trochanteric pain, with implications for targeted therapeutic exercise.

Movement and muscle recruitment variations in those with gluteal tendinopathy

Movement and muscle recruitment patterns have also been shown to be altered in those with gluteal tendinopathy and GTPS.

Kinematic and kinetic alterations in gluteal tendinopathy and GTPS

Biomechanical studies have revealed important alterations in kinematic and kinetic variables in populations with gluteal tendinopathy. Those with greater trochanteric pain are more likely to move in ways that increase load on the abductor mechanism.

Compared with people without hip pain, people with gluteal tendinopathy walked with 9-33% higher external hip adduction moments across stance phase of gait. The external hip adduction moment reflects the load absorbed across the lateral soft tissues that need to balance these forces.14

You can read more about this top hip paper here: Kinematics and kinetics during walking in individuals with gluteal tendinopathy.

The strongest contributors to the variability in these moments were greater contralateral pelvic drop in late stance and greater contralateral trunk lean in early stance.14 Frontal plane kinematic alterations have also been demonstrated in those with gluteal tendinopathy during other loading tasks, such as single leg stance and stair climbing.

Hip abductor muscle recruitment changes in those with gluteal tendinopathy or GTPS

EMG studies have consistently reported findings of upregulation of abductor muscle recruitment and a lack of recruitment variability in walking.15 In participants with gluteal tendinopathy, extended bursts of activity in the middle and posterior portions of the gluteus minimus and medius muscle occur during early to mid-stance phase of gait and there is greater contribution of TFL muscle activity in this loading phase.15 This reflects a lack of motor precision and loss of normal load-sharing strategies.

These alterations may be related to abductor muscle weakness and atrophy, a pain response, or may have been present prior to the development of pain. The evidence that is available is cross-sectional in nature, so it is not possible at this stage to determine the relationship with pathoaetiology of gluteal tendinopathy. As these muscle and movement deficits result in potential provocative loads of the lateral soft tissues, muscle weakness, atrophy and movement variations make appropriate targets for intervention.

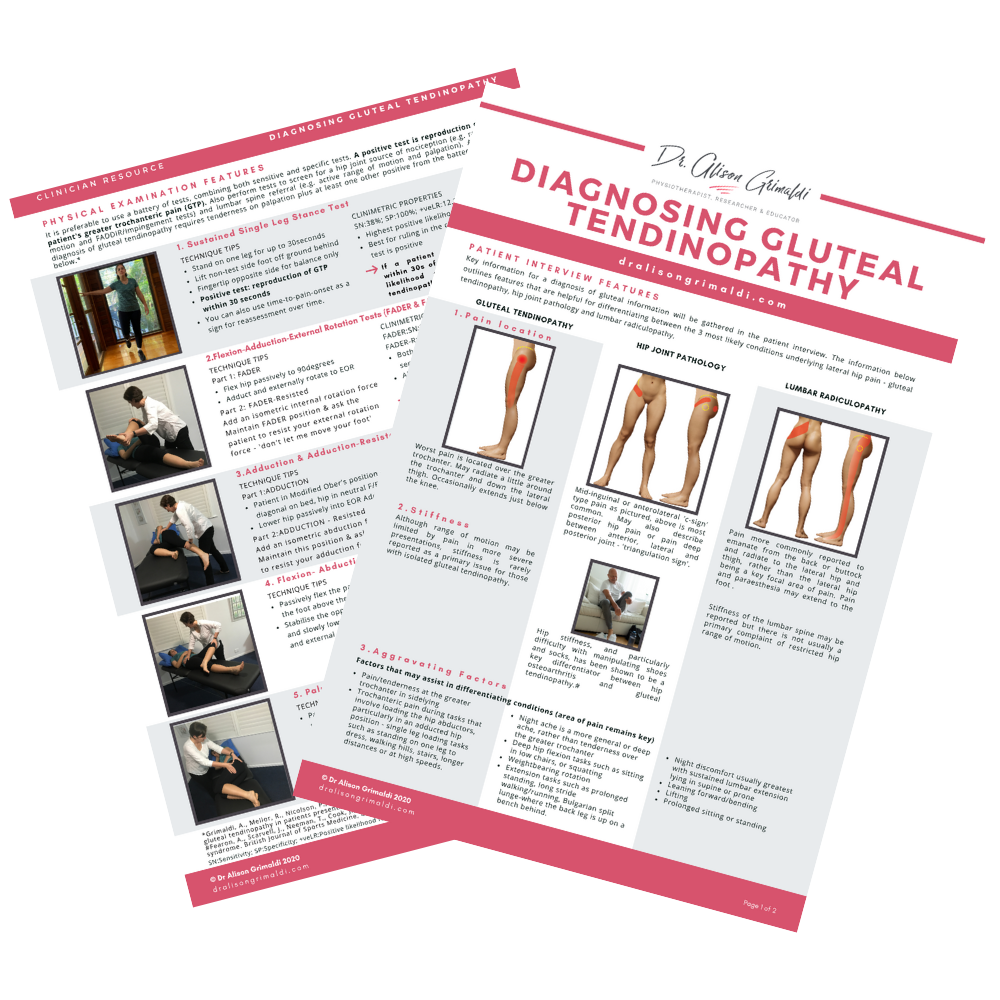

Diagnosis of gluteal tendinopathy

The clinical diagnosis of gluteal tendinopathy involves palpation of the greater trochanter and a battery of tests that ideally combine compressive and tensile loading of the gluteal tendons. Clinicians often rely on palpation and perhaps 1-2 other tests according to survey studies of physiotherapists in the UK, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand.

You can read more about diagnosis and the results of these survey studies in my previous blog: Diagnosing gluteal tendinopathy in clinical practice.

While tenderness on palpation of the greater trochanter is a cardinal sign of gluteal tendinopathy and GTPS, evidence suggests that this test is most useful for ruling out gluteal tendinopathy when the patient is not tender on palpation.16 This means, diagnosis of gluteal tendinopathy should NOT be made on palpation alone.

To optimize diagnostic accuracy, using a test battery for diagnosis of gluteal tendinopathy is recommended.

The clinical test battery for gluteal tendinopathy that we used in the LEAP randomized clinical trial and that I use in my own clinical practice includes:

- Sustained single leg stance,

- FADER & FADER-R (Resisted),

- FABER (also used as part of the differentiation from hip joint related pain),

- Adduction & Adduction-R (Resisted), and

- Palpation

Differential diagnosis of lateral hip pain will also include a range of patient interview questions and physical tests to rule out other possible causes, as outlined above.

Treatment of gluteal tendinopathy and GTPS

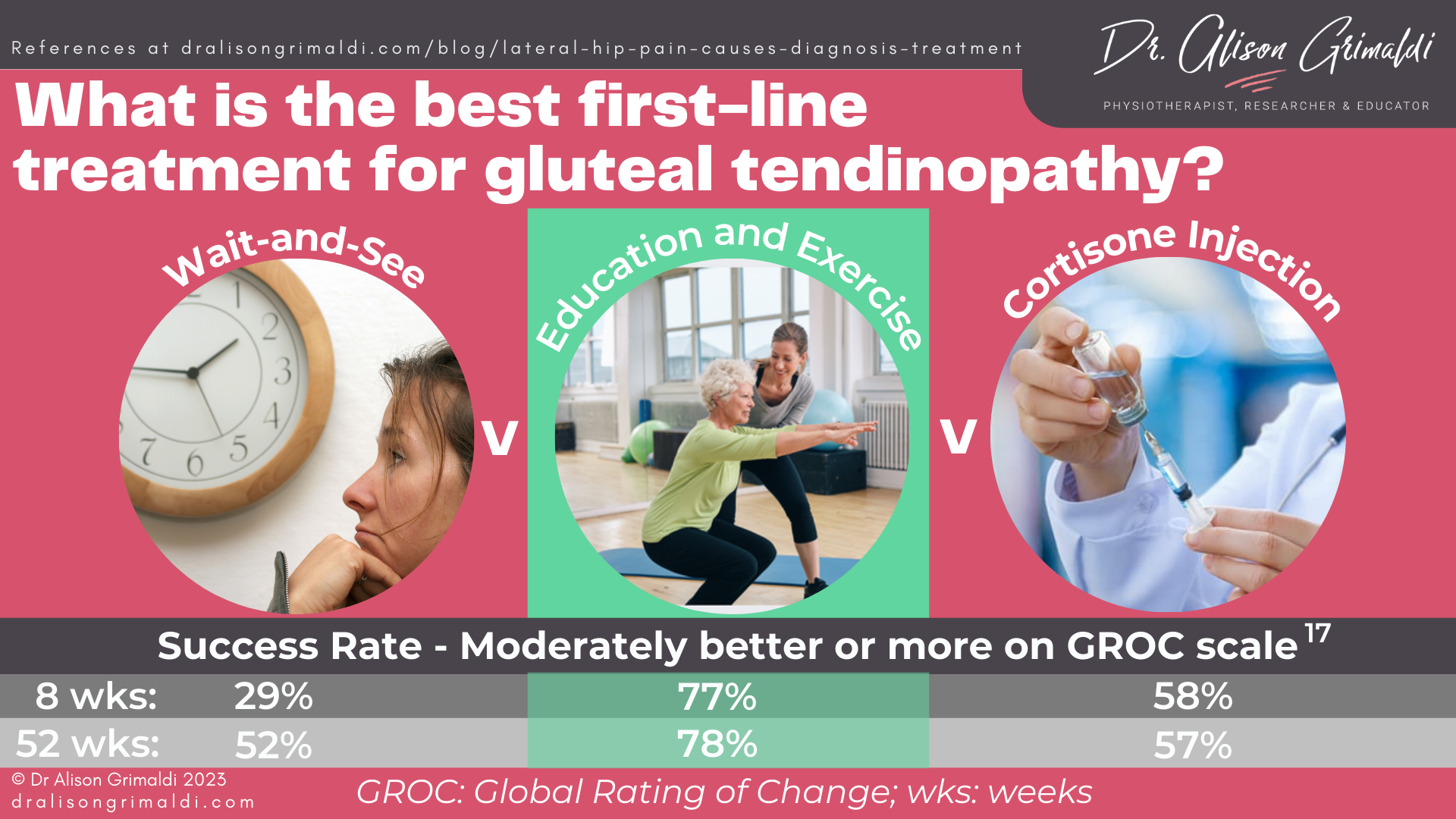

Traditional treatments of soft-tissue related lateral hip pain evolved from the assumption that the trochanteric pain was associated with tightness or the iliotibial band and an inflammatory condition of the trochanteric bursae. Neither of these assumptions have been supported by the evidence, and contemporary management involves much more active approaches to optimizing loading of the gluteal tendons.

Or that’s what the evidence has shown is the best first-line management of gluteal tendinopathy.17 Unfortunately corticosteroid injection (CSI) for trochanteric pain remains the predominant medical management in community care, despite the fact that the LEAP randomized clinical trial (RCT) demonstrated circa 20% higher success rates from an Education and Exercise approach than CSI in both the short and long term.17

When a patient is referred for physiotherapy intervention, a CSI is often provided in advance, with the aim of assisting the rehabilitative process. But does corticosteroid injection aid or hinder our rehabilitation process? < Read more in this blog.

The LEAP trial education and exercise approach to management of gluteal tendinopathy

The education component of the LEAP education and exercise intervention for gluteal tendinopathy aimed to help participants better understand and manage their condition. Load management is a core tenet of this approach.

Education and load management for gluteal tendinopathy

The general principle of ‘load management’ appears to have been well translated into clinical practice, with almost all physiotherapists surveyed in the UK, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand using load management in their treatment of GTPS. Despite this, there are still a reasonable number of physio’s who include ITB stretching in their exercise program, which is inconsistent with an approach that aims to reduce exposure of the soft tissues to compressive loading. It is evident, that load management of gluteal tendinopathy means different things to different health professionals.

Are you still prescribing ITB stretching for gluteal tendinopathy or GTPS?

What does load management mean to you?

Load management is not just doing less. Load management for gluteal tendinopathy involves overall advice around managing activity levels, as well as an initial reduction of cumulative exposure to adduction-related compressive loading, including advice around sustained sitting and standing positions and movement training to reduce excessive dynamic adduction in everyday functional tasks. This education needs to be provided in a non-threatening manner, empowering rather than paralyzing our patients with fear.

Individualized advice around specific physical activities that patients are engaged in can be an extremely important of this load management approach. Wherever possible we want to keep patients active, so unless the patient’s presentation is severe, modifying rather than completely removing activity is preferable initially.

For example, there are exercises in the gym, yoga and Pilates that can be provocative for gluteal tendinopathy. Modifying or swapping out some of these exercises can make a huge difference. Click on the links to read more about modifying gym, yoga or Pilates exercise for hip pain.

Exercise therapy for gluteal tendinopathy and GTPS

The exercise program provided to participants of the LEAP RCT included hip abductor isometrics, a functional loading program with a focus on optimizing dynamic frontal plane control during weightbearing or closed-chain tasks, and a frontal plane strengthening program using heavy-slow loading in weightbearing.

You can read more here about the development of this successful program for gluteal tendinopathy. In the survey studies I’ve mentioned above, almost all surveyed physiotherapists are providing strengthening exercises, but less attention is paid it seems to gait training and functional movement training. This is despite the clear evidence that movement patterns are altered in those with gluteal tendinopathy and particularly excessive frontal plane hip and trunk movement appears to excessively load the gluteal tendons.

You can read more here about how physiotherapists treat gluteal tendinopathy.

It is unclear if improvements in movement patterns and dynamic loading of the soft tissues of the greater trochanter helped mediate the positive effects of the LEAP RCT, as kinematic assessment was not performed again at the end of the active intervention period.

Strength testing was performed at the end of the active intervention, but the recent mediator analysis we published showed that the positive effect of the education and exercise approach compared with the CSI and wait and see groups, was not mediated by strength changes. This means that improvement in hip abductor muscle strength did not appear to be a significant factor in the between-group differences in outcomes.

This analysis revealed that, of the factors available for analysis, improvements in patient specific function, pain constancy, and pain self-efficacy generated through the education and exercise program mediated the superior effects of this approach relative to the other groups (CSI and wait-and-see groups). You can read more here about what this study tells us about how education and exercise helps gluteal tendinopathy.

Hormone replacement therapy for GTPS

There is only one study to date that has assessed the effect of adding hormone therapy to an intervention for GTPS. The GloBE RCT assessed the effect of a transdermal hormone therapy cream and sham cream, on 2 different exercise programs.18

Overall, the hormone therapy didn’t seem to make a difference, but when participants were stratified on BMI, there was a between group difference:

- Those with a BMI less than 25 who used the hormone cream had significantly higher VISA-G scores (better outcomes) at all time points compared with those in the placebo cream group.

- There was no difference between the hormone therapy and placebo groups for participants with a BMI ≥ 25.

You can read more here about this study that looked at the value of hormone therapy for GTPS.

I hope you’ve found this blog on causes, diagnosis and treatment of lateral hip pain helpful. You’ll find plenty of other detail on this site, via the links throughout this blog.

Want to help more people who visit your clinic with lateral hip pain?

For assistance in applying this information in a clinical environment, I recommend you take my Lateral Hip & Buttock Pain online course, and an online or practical workshop on this topic.

-

- The various joint-related, soft tissue-related and nerve-related conditions associated with lateral hip and buttock pain, their mechanisms, associated impairments, clinical diagnostic tests and management approaches.

- Perform diagnostic tests for lateral hip and buttock pain and use that information for differential diagnosis of the most likely source of nociception or a primary clinical entity

- Provide evidence-based load management and exercise strategies for lateral hip pain

- Assess and develop management strategies for posterior hip joint instability

- Recognise occurrence of and potential drivers for extra-articular impingements such as ischiofemoral and greater trochanteric impingement

- Develop management strategies for these extra-articular bony impingements

- Differentially diagnose ischial pain, including diagnostic tests for proximal hamstring tendinopathy

- Apply neurodynamic assessment and mobilisation techniques relevant to the lateral hip and buttock, and consider the impact of soft tissue interfaces

- Recognise the important anatomical relationships and functional roles of the deep external rotators

- HELP MORE PEOPLE WITH LATERAL HIP & BUTTOCK PAIN

Check Out Some More Relevant Blogs

References

- Segal NA, Felson DT, Torner JC, Zhu Y, Curtis JR, Niu J, Nevitt MC; Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study Group. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: epidemiology and associated factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007 Aug;88(8):988-92. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.04.014.

- Lange J, Tvedesøe C, Lund B, Bohn MB. Low prevalence of trochanteric bursitis in patients with refractory lateral hip pain. Dan Med J. 2022 Jun 15;69(7):A09210714.

- Long SS, Surrey DE, Nazarian LN. Sonography of greater trochanteric pain syndrome and the rarity of primary bursitis. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2013;201(5):1083-1086.

- Blankenbaker DG, Ullrick SR, Davis KW, De Smet AA, Haaland B, Fine JP. Correlation of MRI findings with clinical findings of trochanteric pain syndrome. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(10):903–909.

- Everett BP, Sherrill G, Nakonezny PA, Wells JE. The relationship between patient-reported outcomes and preoperative pain characteristics in patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty. Bone Jt Open. 2022;3(4):332-339.

- Poulsen E, Overgaard S, Vestergaard JT, Christensen HW, Hartvigsen J. Pain distribution in primary care patients with hip osteoarthritis. Fam Pract. 2016;33(6):601–606.

- McCrory P, Bell S. Nerve entrapment syndromes as a cause of pain in the hip, groin and buttock. Sports Med. 1999 Apr;27(4):261-74. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199927040-00005.

- Schmid AB, Hailey L, Tampin B. Entrapment neuropathies: Challenging common beliefs with novel evidence. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018 Feb;48(2):58-62.

- Dutton RA. Stress Fractures of the Hip and Pelvis. Clin Sports Med. 2021 Apr;40(2):363-374. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2020.11.007.

- Lee BJ, Song J. Trochanteric stress fracture in a female window cleaner. Hip Pelvis. 2016 Mar;28(1):60-3. doi: 10.5371/hp.2016.28.1.60.

- Birnbaum K, Siebert CH, Pandorf T, Schopphoff E, Prescher A, Niethard FU. Anatomical and biomechanical investigations of the iliotibial tract. Surgical and Radiological Anatomy. 2004;26(6):433-446.

- Allison K, Vicenzino B, Wrigley T, Grimaldi A, Hodges P, Bennell K. Hip abductor muscle weakness in individuals with gluteal tendinopathy. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2016;48(3):346–352.

- Cowan RM, Semciw AI, Pizzari T, et al. Muscle size and quality of the gluteal muscles and tensor fasciae latae in women with Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome. Clinical Anatomy, 2019;33(7):1082-1090.

- Allison K, Wrigley TV, Vicenzino B, Bennell KL, Grimaldi A, Hodges PW. Kinematics and kinetics during walking in individuals with gluteal tendinopathy. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2016 Feb;32:56-63. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2016.01.003. Epub 2016 Jan 15. PMID: 26827150.

- Allison K, Salomoni S, Bennell K, et al. Hip abductor muscle activity during walking in individuals with gluteal tendinopathy. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2018;28(2), pp.686-695.

- Grimaldi A, Mellor R, Nicolson P, Hodges P, Bennell K, Vicenzino B. Utility of clinical tests to diagnose MRI-confirmed gluteal tendinopathy in patients presenting with lateral hip pain. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;51(6):519-524.

- Mellor, R., Bennell, K., Grimaldi, A., Nicolson, P., Kasza, J., Hodges, P., Wajswelner, H. and Vicenzino, B., 2018. Education plus exercise versus corticosteroid injection use versus a wait and see approach on global outcome and pain from gluteal tendinopathy: prospective, single blinded, randomised clinical trial. British Medical Journal, p.k1662.

- Cowan RM, Ganderton CL, Cook J, Semciw AI, Long DM, Pizzari T. Does Menopausal Hormone Therapy, Exercise, or Both Improve Pain and Function in Postmenopausal Women With Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome? A 2 × 2 Factorial Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Sports Med. 2022 Feb;50(2):515-525. doi: 10.1177/03635465211061142. Epub 2021 Dec 13. PMID: 34898293.