Hypermobility and the Hip

Last month we started our journey into hypermobility, firstly focusing on how to best identify joint hypermobility syndromes and measure their impact. This month, we’re going to dive deeper into the relationship between hypermobility, hip conditions and outcomes of management of these conditions in hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (hEDS) and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders (HSDs).

Hypermobility and the hip ... let's take a look at the links. Those with hypermobility are more likely to have structural variations such as acetabular dysplasia, femoral malversion, and labral and capsular deficiency, all of which may predispose to the development of hip pain and osteoarthritis. It’s important then to be aware of these links in patients presenting with hip pain and generalised, local or historical hypermobility.

We dived deeper into:

- Terminology & prevalence of hypermobility related conditions

- Diagnosing hEDS and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders

- The Spider – a tool for measuring the multisystem impact of hEDS and HSD

- The relationship between hypermobility, hip conditions and treatment outcomes

- Q & A + member discussion

Recordings are now available! Join today to benefit from all Hip Academy inclusions!

This blog will explore the following relationships:

- Hypermobility and acetabular dysplasia

- Hypermobility and femoral malversion

- Hypermobility and labral and capsular deficiency

- Hypermobility and the development of osteoarthritis

- Hypermobility and outcomes of hip surgery

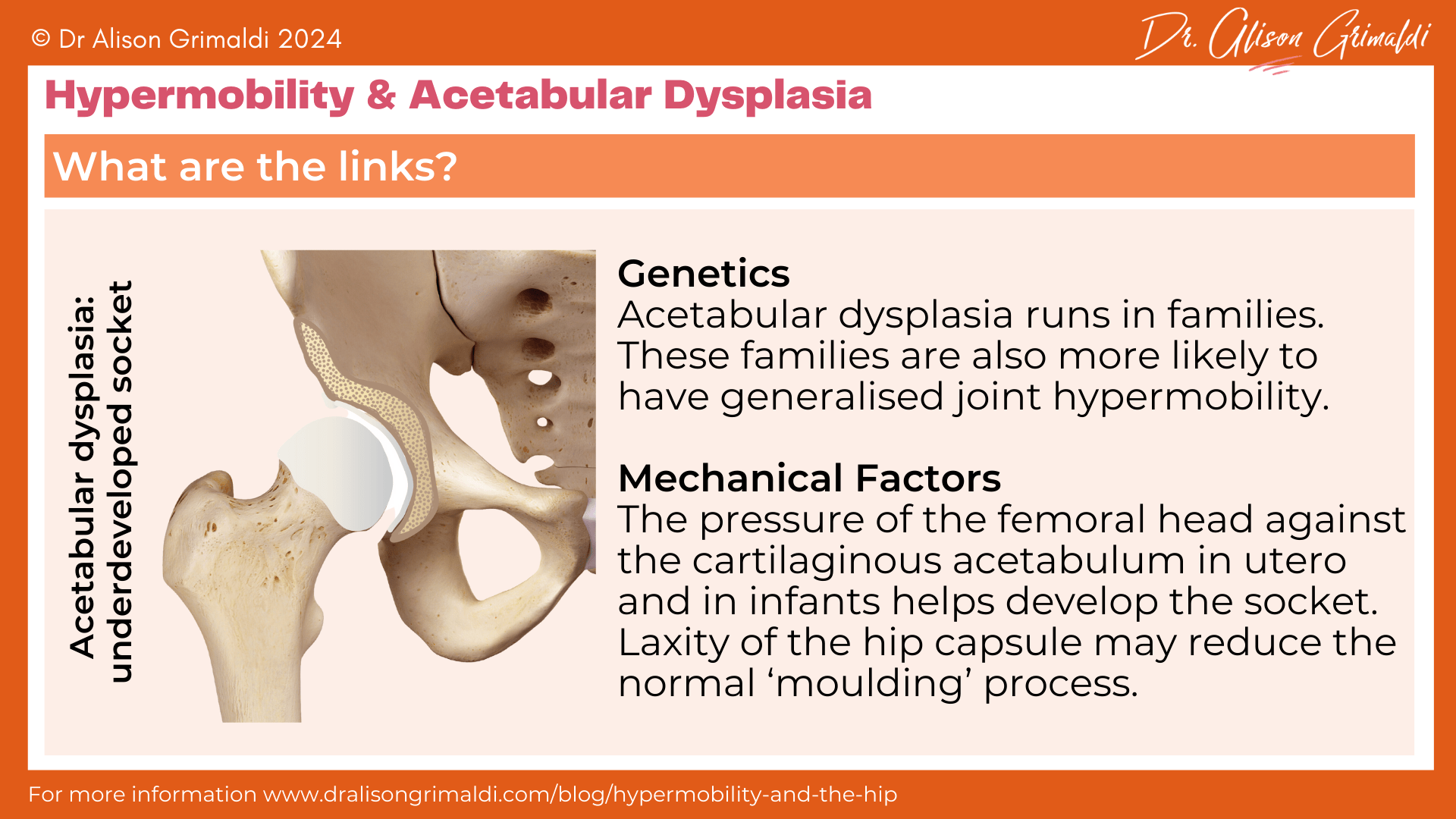

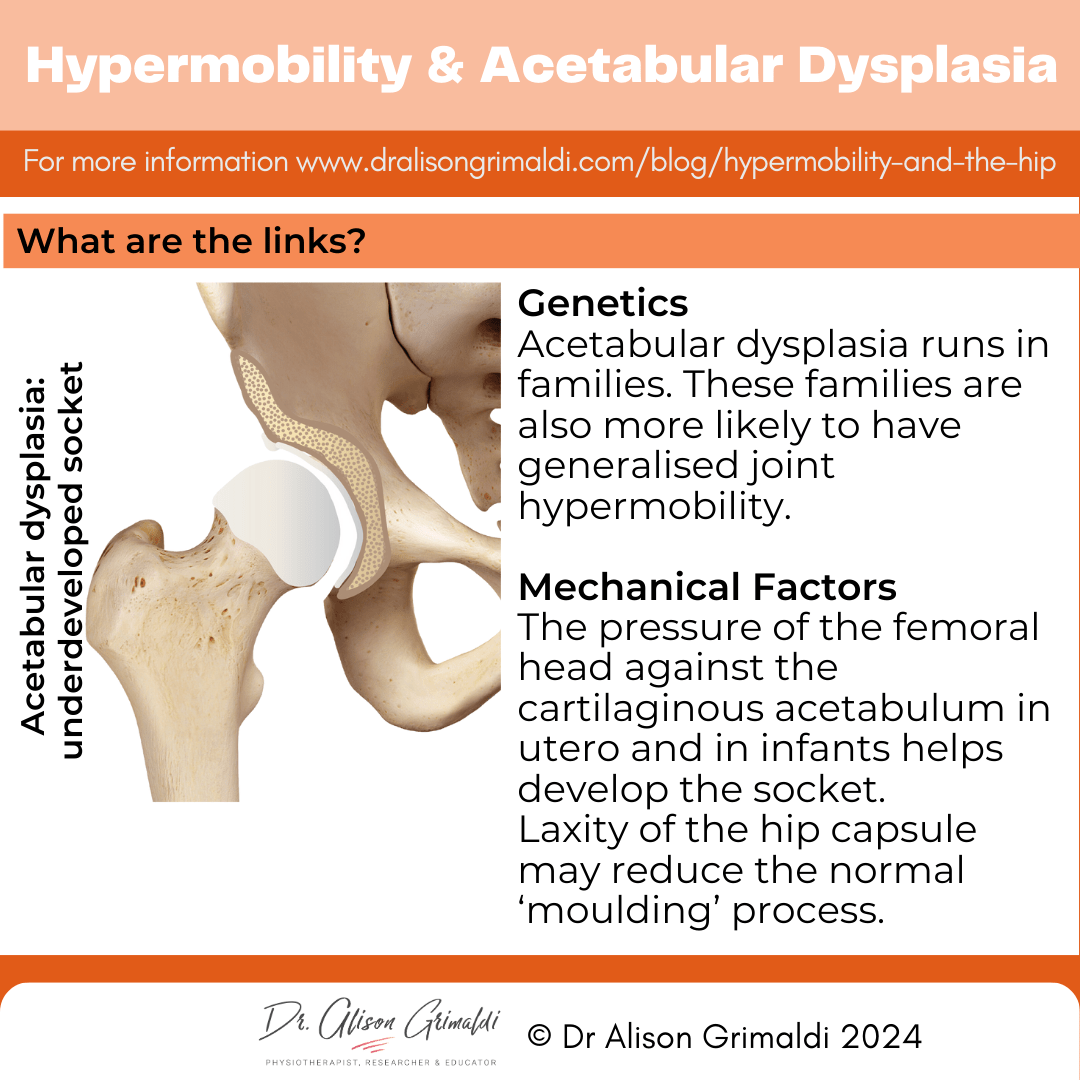

Hypermobility and acetabular dysplasia

Acetabular dysplasia refers to undercoverage of the femoral head due to a lack of adequate development of the acetabular socket in utero and/or infancy. This may be referred to as developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), with the older term ‘congenital dislocation of the hip’ previously used to describe the effect of this underdevelopment in infants - a dislocated hip, where the femoral head is not contained within the shallow socket. In the absence of frank dislocation, acetabular dysplasia (sometimes also simply called hip dysplasia) may go unrecognised until adulthood often in association with the development of hip pain.

You can read more about the various factors involved in the development of acetabular dysplasia in my blog on this topic. Links have been made between hypermobility and acetabular dysplasia in both children and adults. It seems there might be 2 different links here – genetic and mechanical.

Genetic links between hypermobility and acetabular dysplasia

The risk of being born with acetabular dysplasia increases significantly in those with a sibling or parent with dysplasia, so there appears to be a genetic factor. Researchers have established that many families with acetabular dysplasia, also have familial joint laxity.1

For some, the genes linked with acetabular dysplasia may be the same genes related to expression of a heritable connective tissue disorder, but hypermobility is not present in all families with acetabular dysplasia, so it was determined to be a separate heritable system.1

Mechanical links between hypermobility and acetabular dysplasia

The other link here may be more mechanical. The development of the acetabular socket is dependent on the hip capsule and ligaments holding the developing femoral head against the socket. As the head grows into a round ball, it should press into the initially flat socket, creating an indentation and ultimately a socket to sit it.

For those with an extra stretchy hip capsule and ligaments, the femoral head may not be held firmly enough against the developing acetabulum, resulting in inadequate depth of the socket.

In a study of 1004 adults presenting with hip pain, 78% of those with acetabular dysplasia without osteoarthritis had generalised joint laxity, compared with only 33% of those with non-dysplastic hips. The odds of having hypermobility were 7 x higher for those with symptomatic acetabular dysplasia versus those with other diagnoses.2

In another study of 175 patients undergoing periacetabular osteotomy to improve joint integrity in those with acetabular dysplasia, prevalence of generalized joint hypermobility was significantly higher than a non-dysplastic control group.3

Those with hypermobility and acetabular dysplasia had lower centre-edge angles (reduced acetabular coverage) and greater lateralisation of the femoral head, than those without hypermobility. Higher Beighton scores were predictive of more severe hip dysplasia.3

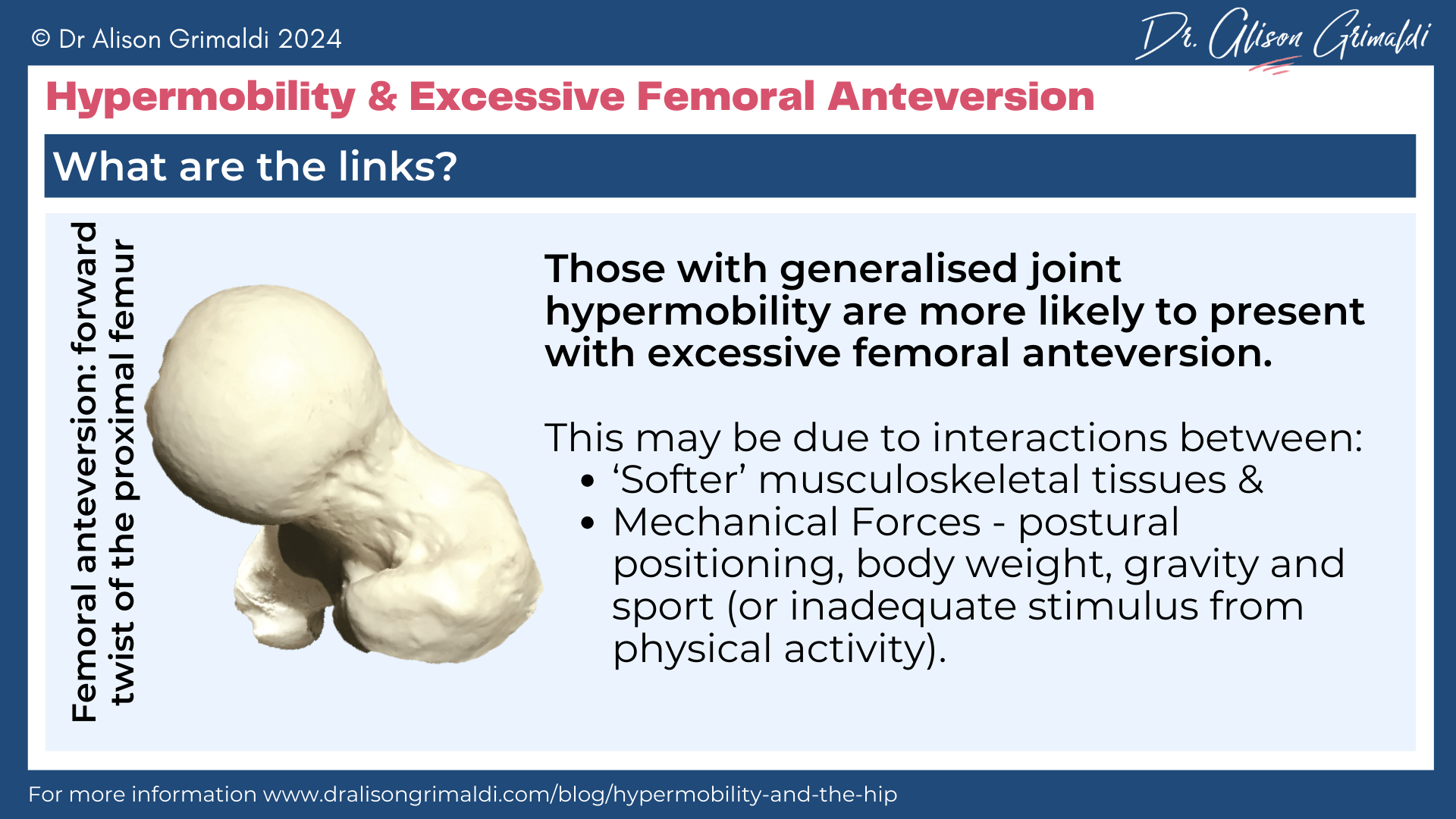

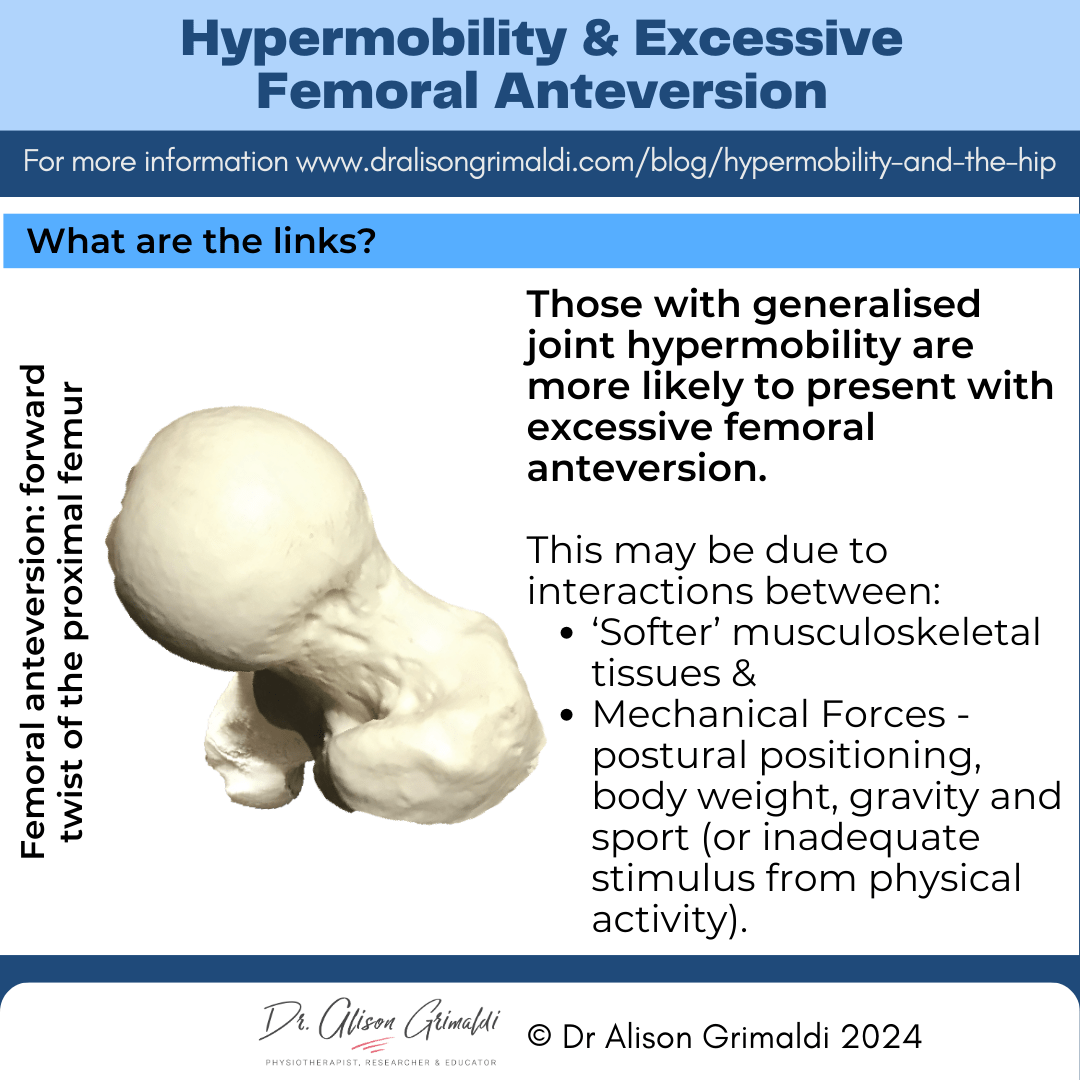

Hypermobility and femoral malversion

Femoral malversion refers to the presence of more than normal (excessive anteversion) or less than normal (retroversion) twist between the proximal and distal femur. A normal amount of twist is 10-20 degrees anteversion (forward twist) of the proximal femur relative to the distal femoral condyles.

Those with generalised joint hypermobility often present with a variety of musculoskeletal variations including excessive femoral anteversion, as well as genu valgum, pes planus, and hallux valgus.4 Castori and colleagues (2017) suggest this may be the result of interactions between “softer” musculoskeletal tissues and mechanical forces (postural positioning, body weight, gravity and sports) during growth and development.4

Hypermobile children do seem to more readily adopt ‘W’ floor sitting postures (bilateral hip internal rotation). This may be an attempt to gain greater postural stability in sitting. In addition, many hypermobile children may not participate as frequently in ‘hip-heavy’ weightbearing sports due to reduced proprioception and greater clumsiness. Reduced weightbearing stimulus may slow the natural ‘de-rotation’ of the femurs during childhood and adolescence.

Have you heard about Hip Academy?

Experience world class education with Dr. Alison Grimaldi's specialised Online Hip Program, designed to enhance your expertise in the Hip and Pelvis. Gain comprehensive access to all Hip Courses, including an extensive eBook series, video library, PDF resources, member meetings, forums, and more.

You can read more about the various factors involved in the development of femoral malversion in my blog on this topic. Femoral malversion is highly prevalent in patients with hip pain undergoing surgery, with severe abnormalities prevalent in 1 of 6 patients (17%).5

Excessive femoral anteversion may occur together with acetabular dysplasia but is a risk factor for more severe hip OA, independent of concurrent acetabular dysplasia. A positive correlation has also been found between the amount of increased anteversion and severity of hip OA.6

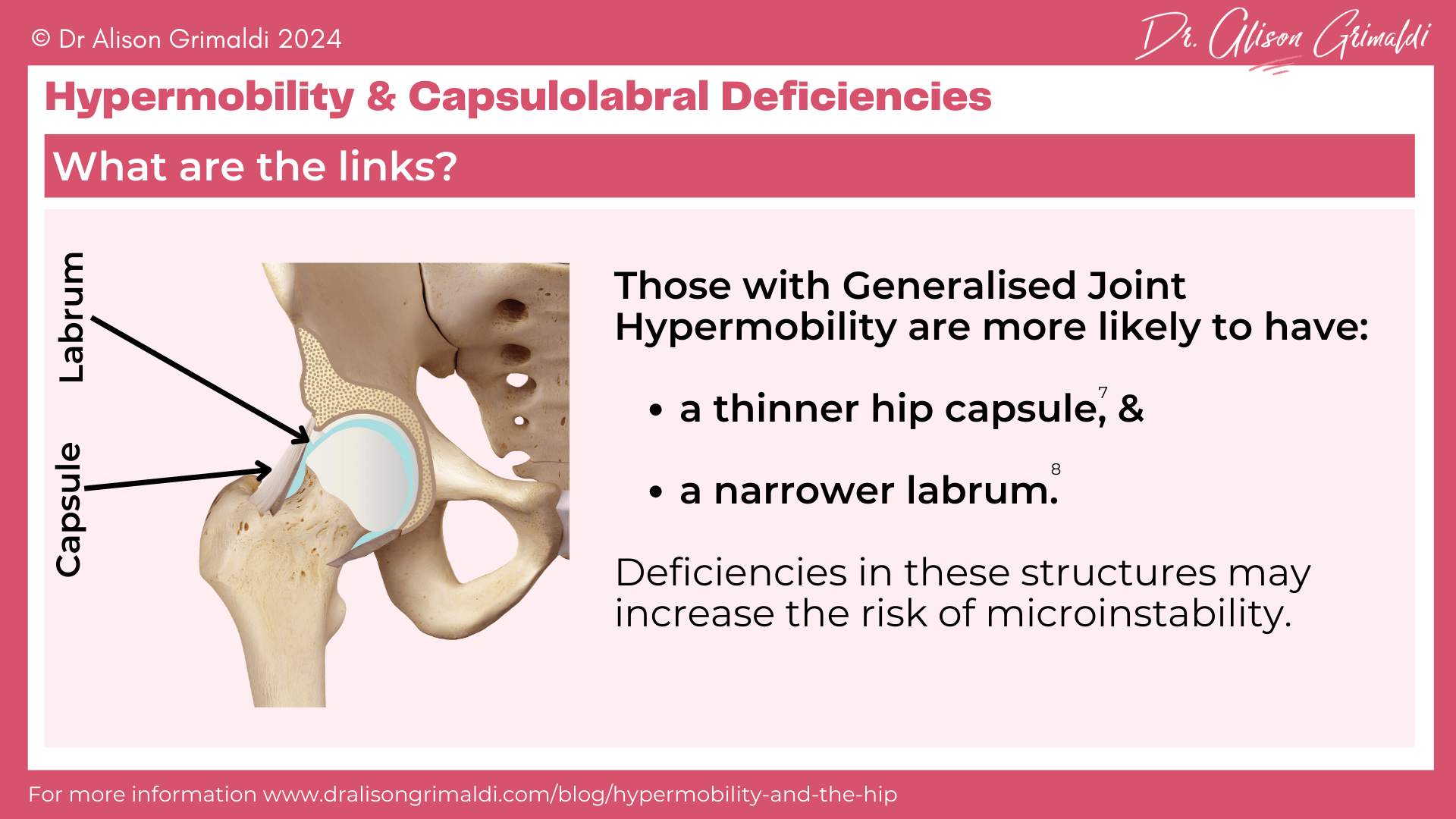

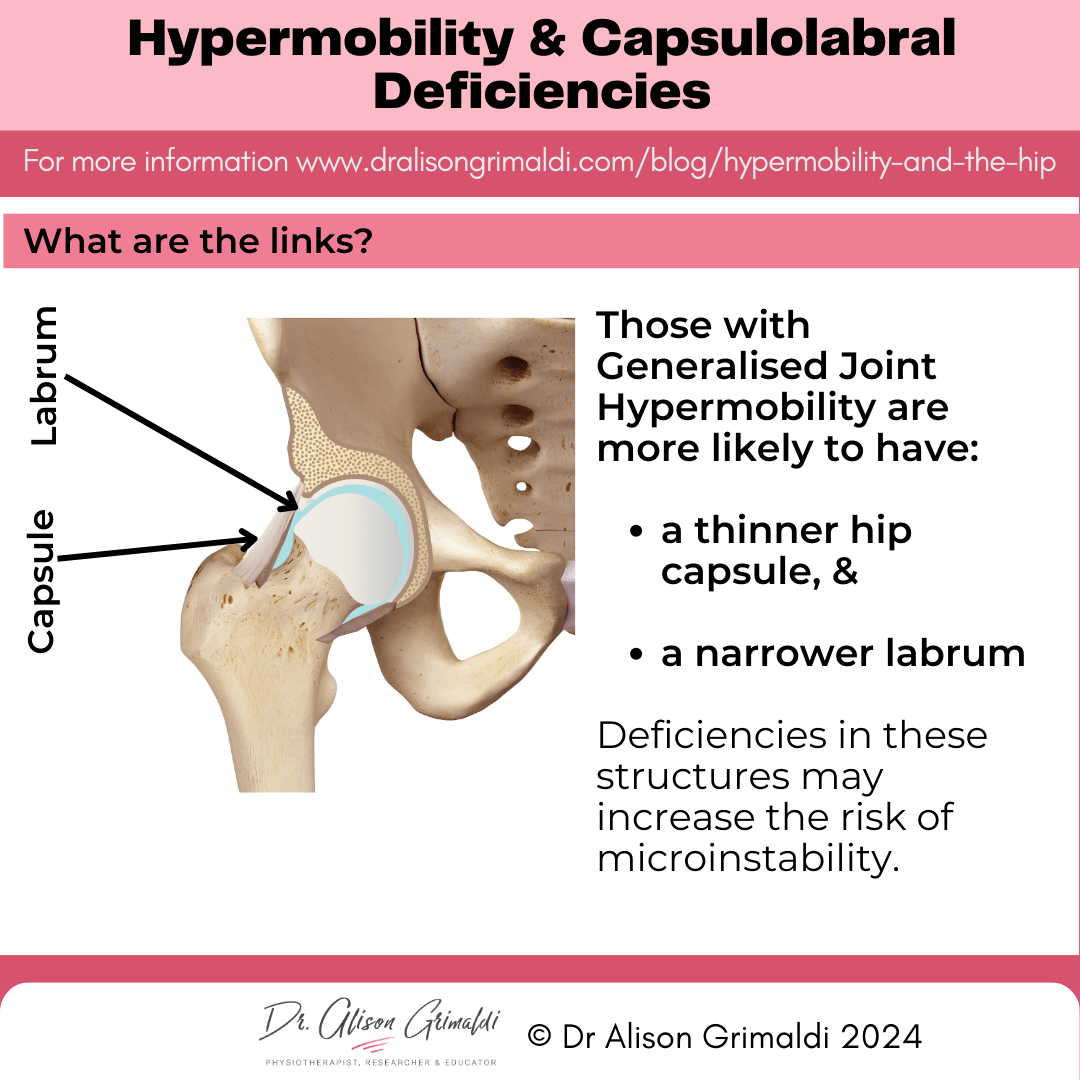

Hypermobility and labral and capsular deficiency

Hypermobile individuals may also have deficiency of both the acetabular labrum and/or the hip capsule, both important structures in joint protection and stability.

Devitt and colleagues reported that the presence of generalised joint hypermobility was predictive of reduced hip capsular thickness - those with GJH having a thinner hip capsule (<10mm) than those without.7

Another study demonstrated that those with a higher Beighton score (≥ 4/9) had a significantly narrower labrum in the superior and anterosuperior aspects of the acetabulum i.e. the labrum doesn’t extend as far from the edge of the acetabulum.8 These particular areas of the labrum are also areas that commonly develop tears.

The labrum normally increases the acetabular surface area by a mean of 22% and the acetabular volume by a mean of 33%.9 While the labrum usually only carries 1-2% of total joint load,10 it has an important role to play in sealing the central compartment and creating the vacuum effect that is critical for joint stability.

If an individual with generalised joint hypermobility in the context of hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome or Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders, also has acetabular dysplasia, this narrow labrum may need to absorb considerably more force. Henak and colleagues reported that in acetabular dysplasia the labrum may absorb 4-11% of bodyweight!10

Want more? Gain access to the entire video library, all online hip courses, the entire ebook series + exclusive access to pdf resources, live meetings & lots more.

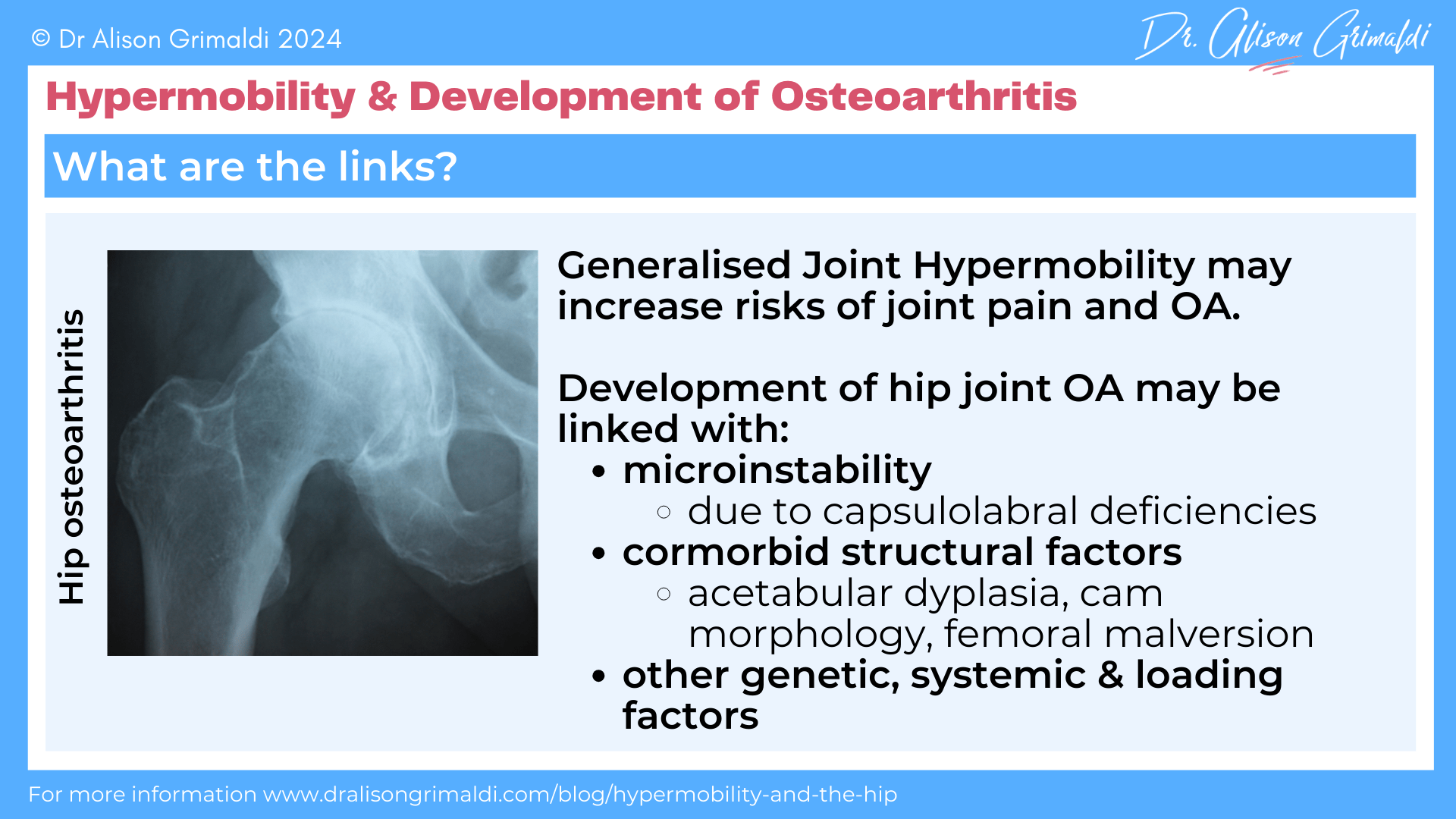

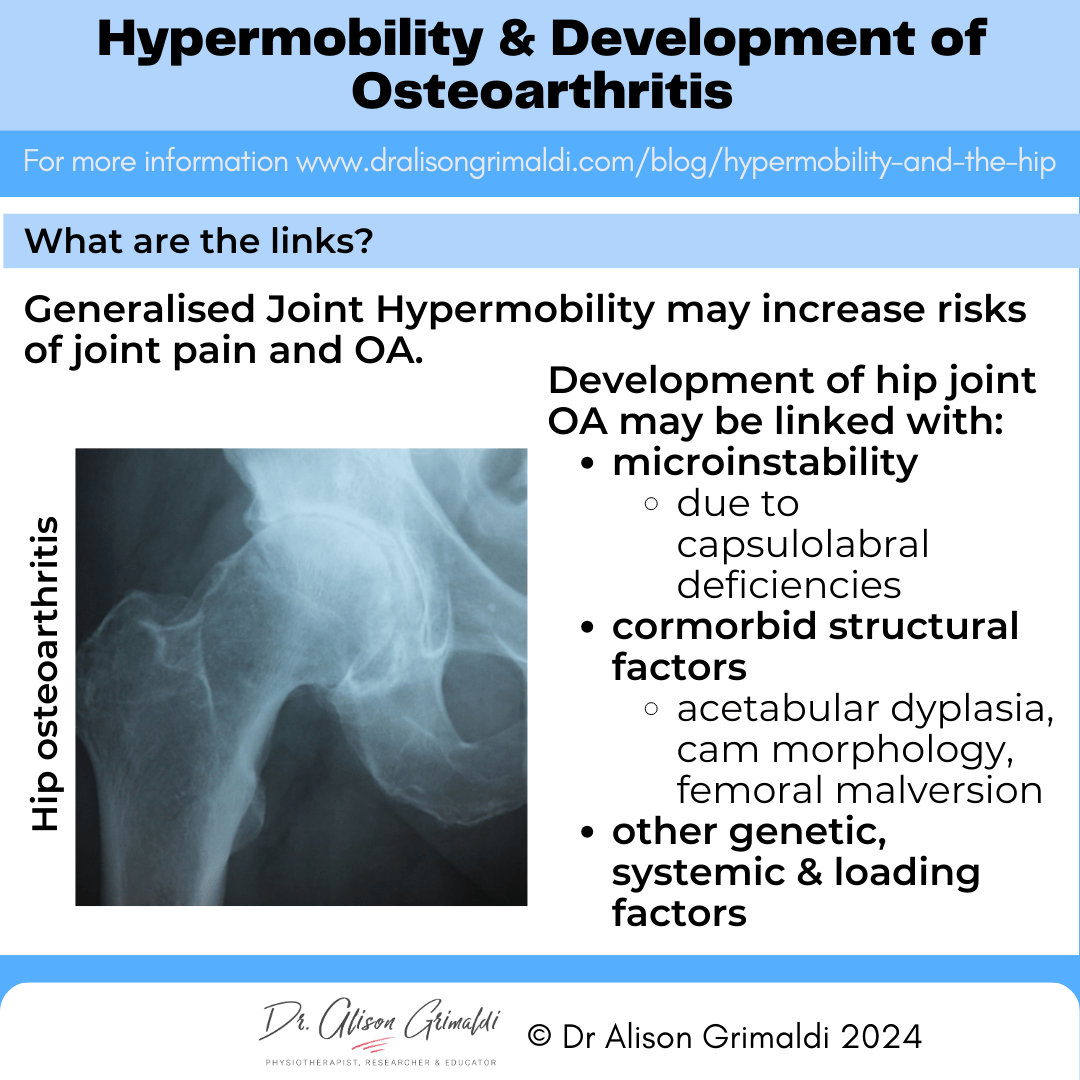

Hypermobility, microinstability and the development of osteoarthritis

The relationship with hip osteoarthritis and hypermobility is a complex one. There are sure to be multiple factors including comorbid structural factors such as acetabular dysplasia, cam morphology, and femoral malversion, as well as loading factors, like postural and movement habits, bodyweight and type and volume of physical activity.

Direct effects are likely to be around capsular and labral deficits. These deficits may lead to microinstability of the hip. Generalised joint hypermobility, using a Beighton score cut-off of more than 5 out of 9, has been included as a major examination feature of a new hip microinstability diagnostic criteria developed to identify hip microinstability in those with hip pain.11

Microinstability is characterised by significant increases in joint rotation, femoral head translation, and an abnormal movement path of femoral head centre. This has been hypothesized to result in abnormal abutment of the femoral head against the acetabulum, increased chondro-labral loads, and increased risk of joint degeneration.12

Of course, excess mobility and pathology will not result in pain in all individuals, but these remain important risk factors for the development of symptoms. Optimising muscular support and reducing exposure to repetitive, sustained, loaded and particularly uncontrolled end-range motion may assist in controlling symptoms.

Have you heard about Hip Academy?

Experience world class education with Dr. Alison Grimaldi's specialised Online Hip Program, designed to enhance your expertise in the Hip and Pelvis. Gain comprehensive access to all Hip Courses, including an extensive eBook series, video library, PDF resources, member meetings, forums, and more.

Hypermobility and outcomes of hip surgery

It has been my experience that those with hypermobile EDS or hypermobility spectrum disorders are more likely to have slower recoveries and poorer outcomes after invasive procedures. Let’s see what the literature says…

Hypermobility and the outcomes of hip arthroscopy

Considering the predisposition to slower recoveries and persistent pain states, it is not surprising that 19 – 40% of patients undergoing hip arthroscopy have generalised joint hypermobility.13 There is variable evidence regarding how this may affect outcomes.

Mojica and colleagues (2022) reported that joint hypermobility is associated with increased risk of postoperative ‘iliopsoas tendinitis’ after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement.14 Iliopsoas tendinitis was diagnosed according to the following criteria: anterior groin pain exacerbated by deep hip flexion, with pain reproduced on one or more of - a resisted straight leg raise, hip flexor stretch, or resisted hip flexion in sitting. It’s possible that such a presentation may be related solely to the iliopsoas, but persistent synovitis/ joint irritability could also be a likely contributor here.

Regardless, the paper shows that hypermobility increases the risks of persistent anterior hip pain following arthroscopic surgery. Patients with these post-operative symptoms not only had a higher mean Beighton score, but there was a linear relationship between these 2 features. For each 1-point increase in the Beighton score, the odds of these anterior hip/iliopsoas symptoms developing in a patient increased by nearly 75%.14

Note that for all of these patients, the capsule was repaired at the end of the procedure. Arthroscopic techniques that do not include capsular repair may increase the severity of microinstability and associated symptoms, and even increase the risk of macroinstability (subluxation/dislocation) in patients with generalised joint hypermobility.

Generalised ligamentous laxity and unrepaired capsulotomy have both been identified as risk factors for dislocation after hip arthroscopy.15 The combination of labral debridement and a lack of capsular repair has been reported to result in the highest overall rate of conversion to total hip arthroplasty after hip arthroscopy (31%) in a general population.16

A recent systematic review of outcomes after hip arthroscopy in patients with generalised joint hypermobility reported no statistically significant differences in outcomes compared to patients without GJH.13 However, it is important to note that all studies were level III and IV evidence, with no randomised clinical trials available, and potential biases were identified in terms of assessment of study outcomes, and loss to follow up (usually those lost to follow up have poorer outcomes).

Almost all hypermobile patients in this review also had capsular repair. The evidence for outcomes in hypermobile individuals who have had labral debridement (trimming of the labrum rather than repair) and/or have not had capsular repair is unknown. The authors of this review also highlighted the high rate of repair in their population and suggested that outcomes of arthroscopy for hypermobile individuals are likely to be most favourable if labral and capsular repair is performed.

Hypermobility and the outcomes of total hip arthroplasty (THA)

With total hip arthroplasty (total hip replacement) comes the low but inherently increased risk of dislocation compared to the native hip. Mechanical loosening of the prosthesis can also result in early revision. As the capsule remains an important restraint for the prosthetic joint, generalised joint hypermobility associated with hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome or other Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders may impact on outcomes of surgery.

Two recent retrospective studies have reported on the outcomes of total hip arthroplasty in the context of Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (the more severe end of the hypermobility spectrum). The incidence of prosthetic revision for those with EDS was 9-10% versus 3-5% for non-EDS patients over 2-10 years.17,18 Higher rates of instability and mechanical loosening were reported in both studies, with dislocation rates at 2 years substantially higher in the EDS group than in the non-EDS group (12% versus 5%). 18

Soft tissue laxity and reduced bone quality associated with EDS is the most likely explanation for significantly higher rates of dislocation and aseptic loosening after THA. Both papers reflected on the need for careful prosthetic selection (more stable prostheses – dual mobility implants, increased offset, larger femoral heads, or a constrained articulation), meticulous capsular closure, intra-operative stability testing, post-operative precautions and use of a shared decision-making process, where patients with EDS are counselled on their elevated risk of instability.17

Considerations for health professionals involved in rehabilitation of EDS patients pre- and post-total hip replacement surgery:

- Pay careful attention to precautions. These have been relaxed in many places, but this is a good time to tighten up those precautions again.

- Aim to optimise health and function of the peri-articular capsular muscles both pre- and post-operatively to reduce excessive joint translations and rotations.

- Aim to optimise load transfer across the prosthesis through attention to postural and movement patterns and global muscle strength.

I hope you have found the information in part 2 of my 2-part hypermobility blog series helpful. In Part 1, I discussed Identifying joint hypermobility syndromes and measuring the impact, be sure to check it out if you missed it!

Hip Academy members recently had a live lecture, and Q & A covering these topics, and the recordings are now available for current and new members, so you might like to join us in Hip Academy!

Learn more about Hypermobility and the Hip in Hip Academy:

Past Meeting: Hypermobility & The Hip

This past live Hip Academy meeting, explored:

- Terminology & prevalence of hypermobility related conditions

- Diagnosing hEDS and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders

- The Spider – a tool for measuring the multisystem impact of hEDS and HSD

- The relationship between hypermobility, hip conditions and treatment outcomes – this will cover links with acetabular dysplasia, femoral malversion, capsulo-labral deficiency, osteoarthritis, and the outcomes of hip arthroscopy and arthroplasty.

Enjoy the benefits of a world class educational Hip Program, specifically designed by Dr Alison Grimaldi to help improve your knowledge surrounding the Hip and Pelvis, and become an expert in your field + Get access to all previous member meeting recordings!

This blog was written by Dr Alison Grimaldi

Dr Alison Grimaldi is a physiotherapist, researcher and educator with over 30 years of clinical experience. She has completed a Bachelor of Physiotherapy, a Masters of Sports Physiotherapy and a PhD, with her doctorate topic in the hip region. Dr Grimaldi is Practice Principal of PhysioTec Physiotherapy in Brisbane and an Adjunct Senior Research Fellow at the University of Queensland. She runs a global Hip Academy and has presented over 100 workshops around the world.

Check Out Some More Relevant Blogs

References:

- Wynne-Davies R. Acetabular dysplasia and familial joint laxity: two etiological factors in congenital dislocation of the hip. A review of 589 patients and their families. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1970 Nov;52(4):704-16.

- Santore RF, Gosey GM, Muldoon MP, Long AA, Healey RM. Hypermobility assessment in 1,004 adult patients presenting with hip pain: correlation with diagnoses and demographics. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020 Nov 4;102(Suppl 2):27-33. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.00060. PMID: 32890043.

- Ping H, Kong X, Zhang H, Luo D, Jiang Q, Chai W. Generalized joint hypermobility is associated with type-a hip dysplasia in patients undergoing periacetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2024 Jul 26. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.23.01030. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39058764.

- Castori M, Tinkle B, Levy H, Grahame R, Malfait F, Hakim A. A framework for the classification of joint hypermobility and related conditions. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2017 Mar;175(1):148-157. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31539. Epub 2017 Feb 1. PMID: 28145606.

- Lerch TD, Todorski IAS, Steppacher SD, Schmaranzer F, Werlen SF, Siebenrock KA, Tannast M. Prevalence of femoral and acetabular version abnormalities in patients with symptomatic hip disease: A Controlled Study of 538 Hips. Am J Sports Med. 2018 Jan;46(1):122-134. doi: 10.1177/0363546517726983. Epub 2017 Sep 22. PMID: 28937786.

- Parker EA, Meyer AM, Nasir M, Willey MC, Brown TS, Westermann RW. Abnormal femoral anteversion is associated with the development of hip osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2021 Sep 2;3(6):e2047-e2058.

- Devitt BM, Smith BN, Stapf R, Tacey M, O'Donnell JM. Generalized joint hypermobility is predictive of hip capsular thickness. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017 Apr 19;5(4):2325967117701882. doi: 10.1177/2325967117701882. PMID: 28451620; PMCID: PMC5400218.

- Haskel JD, Kaplan DJ, Kirschner N, Fried JW, Samim M, Burke C, Youm T. Generalized joint hypermobility is associated with decreased hip labrum width: a magnetic resonance imaging-based study. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2021 Mar 15;3(3):e765-e771. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2021.01.017. PMID: 34195643; PMCID: PMC8220610.

- Ferguson SJ, Bryant JT, Ganz R, Ito K. An in vitro investigation of the acetabular labral seal in hip joint mechanics. J Biomech. 2003 Feb;36(2):171-8. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00365-2. PMID: 12547354.

- Henak CR, Ellis BJ, Harris MD, Anderson AE, Peters CL, Weiss JA. Role of the acetabular labrum in load support across the hip joint. J Biomech. 2011 Aug 11;44(12):2201-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.06.011. Epub 2011 Jul 14. PMID: 21757198; PMCID: PMC3225073.

- Khanduja V, Darby N, O'Donnell J, Bonin N, Safran MR; International Microinstability Expert Panel. Diagnosing Hip Microinstability: an international consensus study using the Delphi methodology. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023 Jan;31(1):40-49. doi: 10.1007/s00167-022-06933-4. Epub 2022 Apr 30. PMID: 35499620; PMCID: PMC9859907.

- Han S, Alexander JW, Thomas VS, Choi J, Harris JD, Doherty DB, Jeffers JRT, Noble PC. Does capsular laxity lead to microinstability of the native hip? Am J Sports Med. 2018 May;46(6):1315-1323. doi: 10.1177/0363546518755717. Epub 2018 Mar 5. PMID: 29505731.

- Arshad Z, Marway P, Shoman H, Ubong S, Hussain A, Khanduja V. Hip arthroscopy in patients with generalized joint hypermobility yields successful outcomes: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2024 May;40(5):1658-1669. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2023.10.047. Epub 2023 Nov 11. PMID: 37952744.

- Mojica ES, Rynecki ND, Akpinar B, Haskel JD, Colasanti CA, Gipsman A, Youm TJ. Joint hypermobility is associated with increased risk of postoperative iliopsoas tendinitis after hip arthroscopy for Femoroacetabular Impingement. Arthroscopy. 2022 Aug;38(8):2451-2458. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2022.02.015. Epub 2022 Feb 25. PMID: 35219796.

- Yeung M, Memon M, Simunovic N, Belzile E, Philippon MJ, Ayeni OR. Gross instability after hip arthroscopy: an analysis of case reports evaluating surgical and patient factors. Arthroscopy. 2016 Jun;32(6):1196-1204.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.01.011. Epub 2016 Mar 21. PMID: 27013107.

- Boos AM, Wang AS, Lamba A, Okoroha KR, Ortiguera CJ, Levy BA, Krych AJ, Hevesi M. Long-term outcomes of primary hip arthroscopy: multicenter analysis at minimum 10-year follow-up with attention to labral and capsular management. Am J Sports Med. 2024 Apr;52(5):1144-1152. doi: 10.1177/03635465241234937. Epub 2024 Mar 22. PMID: 38516883.

- Kubsad S, Thenuwara S, Green W, Kurian S, Kishan A, Harris AB, Golladay GJ, Thakkar SC. 10-year cumulative incidence and indications for revision total joint arthroplasty for patients who have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. J Arthroplasty. 2024 Jun 25:S0883-5403(24)00638-7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2024.06.037. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38936437.

- Fuqua A, Worden JA, Ross B, Bonsu JM, Premkumar A. Outcomes of Total Hip Arthroplasty in patients who have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: A Matched Cohort Study. J Arthroplasty. 2024 Jul 11:S0883-5403(24)00694-6. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2024.07.008. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39002769.